By Emil Bjerg, journalist and editor of The World Financial Review

The global influx of K-pop symbolizes South Korea’s new-found prosperity. But the exponential growth of the scene has also led to the mental exhaustion of artists and fears of monopoly formation. We take a look at the phenomena and industry that’s fighting to find a sustainable path ahead.

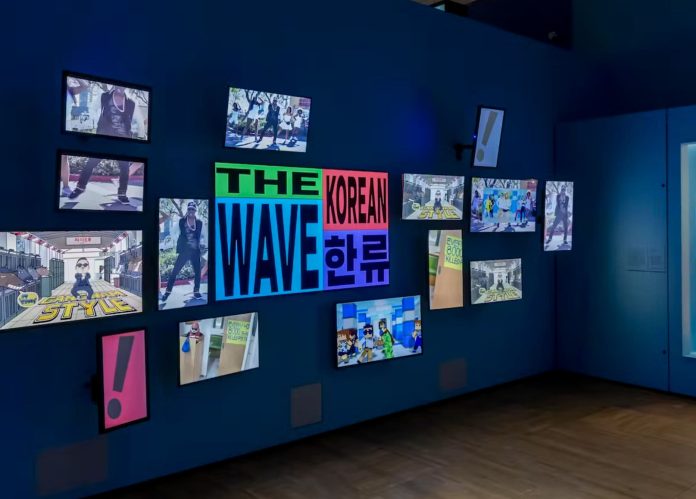

South Korea’s cultural moment has hit the epicenters of mainstream success in recent years. Today, most global culture consumers participate in the ‘Hallyu’ economy, also known as ‘the Korean Wave’. In 2020, Parasite became the first non-American movie to win an Oscar for Best Picture, and shortly after, Squid Game became the most watched series ever on Netflix. In music, BTS and Blackpink have become household names selling out stadiums worldwide. Today, K-pop, along with other kinds of K-content, is a solid contributor to South Korea’s GDP.

The rise of K-pop in numbers

If K-pop was a stock, it’s a stock you’d like to have invested in in the late 00s. According to Statista, the trend toward the billion-dollar industry that K-pop is today starts around 2010. A few years later, in 2012, the chart-topper Gangnam Style, referencing a posh Seoul neighborhood, was released. The song’s music video became the first video on YouTube to reach one billion views. The growth has been exponential ever since.

From a political point of view, K-pop and other forms of K-content are considered South Korea’s ‘soft power’. But it’s a soft power that easily translates to economic might. Take the boyband BTS as an example.

In 2021, the band sold around 1.35 million tickets to an online concert, grossing 71 million USD for a single show from viewers in 135 countries. In 2019, the band generated an impressive 4.65 billion USD for the South Korean economy. Statista states that’s 0.3 percent of the total South Korean GDP for that year.

According to Allie Market Industry, the global K-pop events market was valued at a staggering $8.1 billion in 2021. Add to that 220 million USD in album export. In 2031, the international K-pop events market is estimated to be a 20 billion USD industry. That’s the equivalent of South Korea’s total GDP in 1974.

As if that’s not enough, K-pop has positive spillover effects on many industries.

| You might also like: |

K-pop and spillover export effects

As Forbes writes, today, K-pop is a top sector in South Korea “alongside cars, IT, and semiconductors.” Cars and IT might generate a higher part of Korea’s GDP, but the soft power of K-pop and K-content has priceless branding value. As noted in a podcast from The Economist: “Soft power does matter in terms of raising awareness, opening the markets […], branding changes how people think about you. K-pop, movies, and tv-shows have been really important in making Korea more interesting to people all over the world.” South Korea’s soft power is big business.

K-pop spills over to tourism, for one. A 2019 survey from the Korean Tourism Organization showed that Hallyu-related tourism made up 7.4 percent of all inbound tourism – more than a million visitors. South Korean fashion and cosmetic products are also seeing an increase in export as die-hard K-pop fans try to emulate the looks of their favorite artists. The cosmetics industry in South Korea reached a value of almost 16 billion USD and is expected to reach 21.5 billion USD by 2027.

Crafted popstars, engineered popularity

The success of K Pop and other cultural products from South Korea is far from coincidental. Most famous K-pop artists are released through one of the ‘Big 4’ labels, SM Entertainment, YG Entertainment, JYP Entertainment, and HYBE Labels.

The Big 4 have meticulously crafted a formula for success, combining irresistible hooks with eye-catching visuals. These entertainment powerhouses engineer not just hits but also the pop stars themselves, carefully selecting and mentoring young talents through rigorous training regimens. In doing so, they create an eye-catching blend of artistry and marketability that has helped K-pop’s meteoric rise on the global stage.

The popular boyband NCT 127, released by SM Entertainment, serves as a great example of the creative entrepreneurship within the K-pop industry. Since the group can only be in one place at a time, NCT 127 replica bands have emerged in China, with plans to expand the franchise even further. Another group, the girl band Aespa, has four real, human members and four avatar members.

Ambitious pop policies

While entrepreneurial labels have engineered the scale of commercial success, the Korean state has played a central part in supporting creative talents.

As fears of a South Korean brain drain spread during the Asian economic crisis in 1998, the Ministry for Sports and Culture was established with a specific focus on supporting music along with fashion, movies, and music. Already then, an intention of making South Korea a cultural superpower was prevalent.

In 2022, the South Koreas Ministry of Economy and Finance prioritized 696 billion won, or 585 million USD, a rise of 43 percent from the 2021 budget.

The ambitious cultural policies have worked – probably more than the most visionary Korean politician in the 90s would have imagined. A recent report by the Ministry of Culture and Sports called K-content “a relief pitcher on the export front”. The report promises continuous state promotion of K-content with the ambition of elevating the cultural industry of Korea to the global top 4.

If anyone is looking for proof that state investment in culture is a good investment, look to South Korea.

K-pop – a symbol of the rise of a country (and its new challenges)

Today, K-pop is a shiny symbol of Korea’s quick rise to prosperity and a highly competitive economy. From a poor agricultural country to a competitive economy, the Korean cultural scene has also gone from local relevance to international glamour.

But K-pop is also a symbol of something darker: the stress and pressure that’s a part of daily life for many South Koreans.

On average, South Koreans work 240 hours more than Americans each year. As Quartz writes: “If there was a prize for the most stressed-out nation in the world, South Korea would make a good contender.” A playful public culture with K-pop, karaoke, and heavy drinking has emerged as a way to release stress from expectations and long working days.

But K-pop is often produced under the same stressful conditions that it’s used as a relief for. K-pop stars undergo a stressful combination of dance, vocal, and instrument training while also having their fitness and weight under close scrutiny. They receive media training and learn several languages to communicate with a global fan base. As Chris Lee, the chief executive of the label SM Culture recently told The Guardian: “We teach them how to have good personalities.”

Add to that the pressure of being a global celebrity in the age of social media. In recent years, a dark undercurrent of eating disorders and suicides resulting from intense pressure has tarnished the glittering image of the industry. The “rise and rise of Korean Culture” is the tragic downfall of some of its best ambassadors.

On April 20, South Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism passed an amendment to protect K-pop artists and K-pop talent. The new rules mandate more transparent financial terms. Besides that, for younger performers, working hours are now limited to 25, 30, or 35 hours per week, depending on age, with protection for underage performers’ education. This change aims to prevent the tragic consequences of intense pressure and maintain the industry’s reputation.

Parallel to that, worries over monopoly formation are spreading. HYBE Entertainment, one of the Big 4 K-pop labels, is currently trying to become the majority shareholder in SM Entertainment, another Big 4 label. HYBE and SM combined could potentially dominate the industry. Combined, they make 66 percent of the industry’s total revenue and 89 percent of the income from performances.

Fans fear a monopoly could increase prices on everything from albums to merchandise to concert tickets. Furthermore, as K-pop expands towards an even bigger billion-dollar industry, original fans worry about the ‘whitewashing’ of their beloved music. With a rise in popularity and the entrance to Western markets, lyrics are increasingly written in English, making fans feel the distinct sound of K-pop is threatened.

Squeezed between entrepreneurial labels, ambitious politicians, mentally exhausted artists, and increasing global demand, K-pop struggles to find balance, but the Hallyu economy shows no signs of slowing down.

This article was originally published on 07 May 2023.