Japan, once the quintessential global economic success story, experienced a dramatic slowdown in growth in the last years of the 20th century and early 2000s. Kalim Siddiqui examines the whys and wherefores.

Between 1950 and 1990, Japan witnessed a remarkable economic and trade expansion and economic modernisation that allowed its economy not only to recover from disastrous war but also to catch up with the per capita income levels and living standards in the industrially advanced economies. Japan had transformed itself from a largely agricultural nation in 1950 to the world’s second-largest economy by 1980. Japan had figured out ways to make high-quality products cheaply, and these products found their way all over the world.

The country’s trade policy during the post-war years was focused on access to Western markets. The strategy was on the promotion of exports, while slow at liberalising imports in sectors where Japan had strong comparative disadvantages. To boost exports, it kept an undervalued yen, subsidised exports, and cheap credits were provided to the export sector, while imports were restricted to maintain trade surpluses. The Sony Walkman, Japanese cars, radios, and TV sets successfully competed and became popular consumer items in international markets. The Japanese management style was widely taught in Western universities, movies like Shogun dominated the box office, and corporate success manuals extolled the virtues of “Japan, Inc.” (Itoh, 1990).

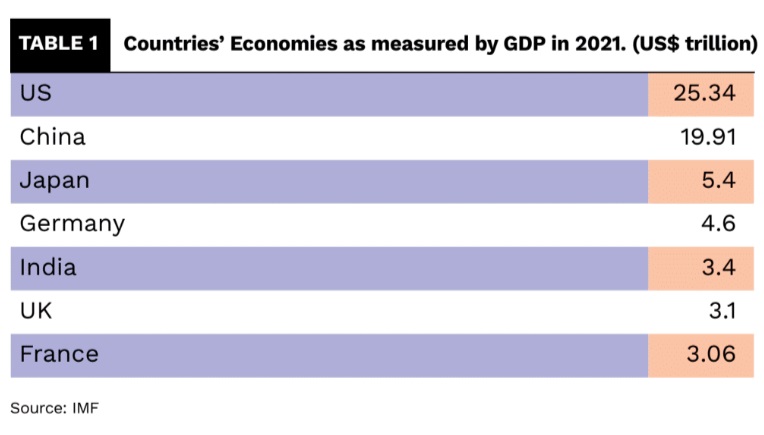

This article aims to examine the key factors that helped Japan to experience rapid growth in GDP between 1950 and 1973 and slow down thereafter, i.e., 1974-90. Moreover, for the last three decades, the country has experienced stagnation, despite some short-lived recovery. I think revisiting the development of the Japanese economy is important because the country is still the world’s third-largest economy and its performance has a big impact on the global economy, more specifically on East Asian economies.

After US troops occupied Japan, they insisted on curtailing the power of feudal elites and others who had supported the war. The US initiated various socioeconomic reforms in Japan, including monarchy reform, a new constitution, and land reforms. The US concluded that breaking the rural landed aristocracy and land monopoly ownership would increase food production to reduce food shortages and the threat of famine. Land reform would increase incomes of small farmers, and this would increase the proportion of the middle class and would help to combat communism in Japan. It seems that land reform was the most effective in supporting and enhancing democracy in the countryside. Through the rural reforms, class relations in the rural areas underwent fundamental changes, with feudal parasitic landlords removed, tenants and small farmers gaining ownership of land and freeing themselves from the shackles of semi-feudal relations (Johnson, 1982).

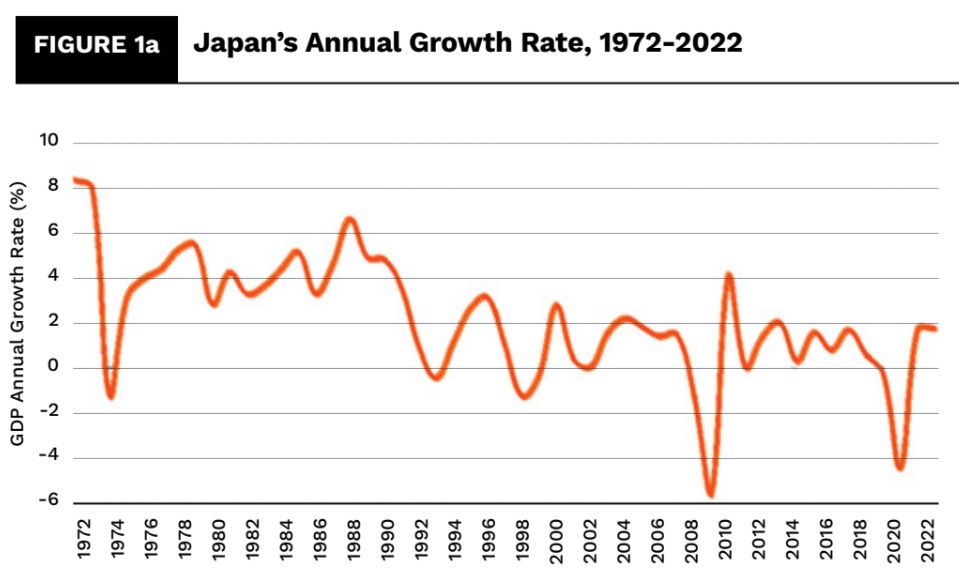

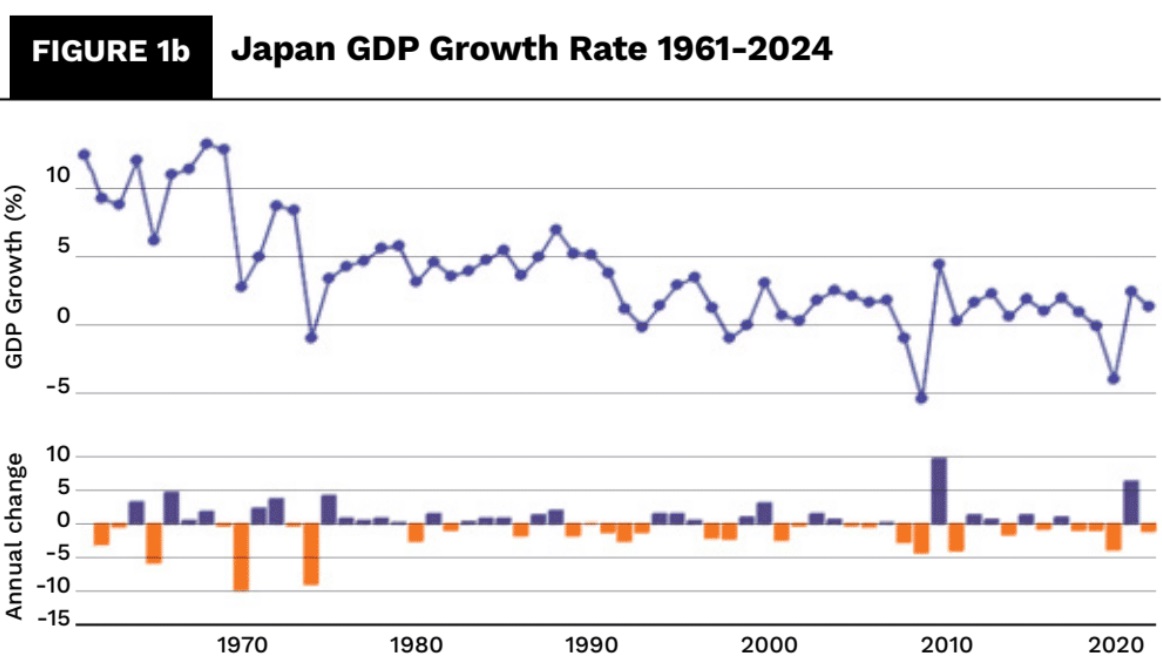

Japan’s businesses followed the traditional concept of the keiretsu, a close-knit network of business interests centred around the banks. These groups took majority shareholder interests in one another, instead of being financed through stocks or bonds and, as such, this “socially controlled” investment provided the perfect conditions to nurture. Japan has witnessed a slowdown in growth rates (see figure 1 and table 1) as all major advanced economies have faced since the 1980s, although Japan did not embrace neoliberal policies as the US and UK did. But still, the country moved towards increased economic liberalism by attacking labour unions’ rights and gradually introducing financial deregulation. This meant that the banking system was no longer the instrument of industrial policy as happened in previous decades (Itoh, 1990).

The nature of capitalist economies has driven changes in income distribution and economic policy, which are the root cause of stagnation and Keynesian policy was unable to explain the causes of stagnation. Under neoliberalism, financial deregulation has led to increased investment in speculative activities in the financial and real estate sectors. And by 1989, it reached such a critical point that the Bank of Japan (BoJ) had to raise interest rates to control inflation. As a result, the asset market threatened the financial system, although the BoJ was able to bail them out and minimise the adverse impact (Itoh, 1990).

However, during the 1980s, the Japanese economy was believed to be poised to overtake the US as the dominant economy, which was due to a dramatic rise in productivity, innovation, and economic organisation. According to Arrighi (1994: 332), Japan’s economic “catch-up” was not only sustained and spectacular but was more so than Germany’s. It had already displaced the US as the dynamic centre of processes of capital accumulation on a world scale. This remarkable economic transformation in Japan was not based on a “free market” policy as mainstream economists suggest, but active state intervention. Chalmers Johnson (1982) challenged the mainstream economists’ view and emphasised that the Japanese state focused on industrialisation and played an important role in the transformation towards a successful economic transformation. Policy intervention includes the promotion of exports, relative state autonomy, coordination between industries and government officials, industrial planning, and a state-directed industrial growth strategy (Johnson, 1982).

However, in 1985, after signing the Plaza Accord, which led to the overvaluation of the Japanese yen, Japan saw a massive shift of the domestic production of labour-

intensive industries overseas into East Asian countries. The appreciated yen led to a rapid rise in foreign investment as capital exports became more profitable and the expansion of overseas production networks. The appreciation of the yen forced Japanese manufacturers to move abroad, by taking advantage of cheap labour, especially in textiles and consumer electronics companies (Siddiqui, 2009a).

Despite the deepening crisis and zero growth rates for decades, Japan’s economy, labour productivity, and the living conditions of people are still quite high, as The Economist notes: “Overall growth has remained sluggish, but growth per head has recently been comparable with others in the G7. Unemployment has been minimal, longevity has increased and inequality has stayed relatively low” (The Economist, 2021).

Japan’s Economic Stagnation

Beginning in the 1990s, Japanese capitalism moved into secular stagnation. This development has provoked debates among academics and policymakers. Japan’s secular stagnation has raised new questions about stagnation and almost zero growth rates, falling real wages, deteriorating working conditions, rising inequalities, and the deepening fiscal crisis of the state (Itoh, 2021; Johnson, 1994).

In the 1990s, in Japan, the development of information technology accompanied the process of restructuring and capital investment, and the business environment became tighter, short-term, and mobile, thus intensifying competition. Trade unions were weakened in the name of labour flexibility and the role of the state in the economy was gradually reduced (Siddiqui, 2009b).

Between 1991 and 2001, Japan’s once red-hot economy was in trouble. An asset bubble had formed in both its housing and stock markets, and when the BoJ implemented a series of steep rises in interest rates to control inflation, Japan’s stock market began to slow down and asset prices fell. Several big banks, due to high levels of speculative investments, faced difficulties and business slowed down, while unemployment rose. As a result, Japan’s economy entered a deep recession. The GDP growth declined and borrowers became insolvent. Big Japanese banks, including the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank and Nippon Credit Bank, experienced a fall in their profits. The days of easy credit from banking networks were long gone (Siddiqui, 2015).

Japan’s share of global exports fell from nearly 9 per cent in 1990 to 4 per cent in 2018. China’s share of global exports rose from around 2 per cent in 1990 to 13 per cent in 2018. Japan’s export sector was adversely affected after the global financial crisis (Siddiqui, 2019a).

The country ran large fiscal deficits from 1998 to 2005 and again following the global financial crisis from 2008 to 2017. Persistent fiscal deficits have resulted in elevated government debt ratios. Japan’s gross debt and net debt, as a share of GDP, have risen from 19 per cent and 64 per cent, respectively, in 1991, to 156 per cent, 238 per cent in 2018 and 250 percent in 2022. Japan’s debt ratios are the highest among the major advanced capitalist countries (as shown in Figure 2).

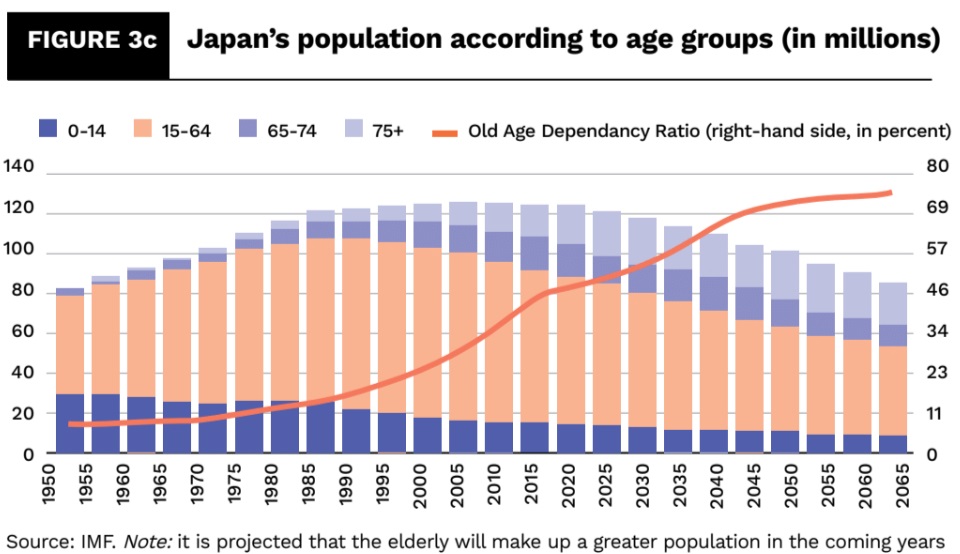

Productivity growth is important for a country’s future growth. In Japan, labour productivity growth has declined in recent decades. Since Japan’s labour force is shrinking, the country needs to attain high labour productivity growth that is sufficient to more than offset the decline in its labour force to ensure increased prosperity in the coming years.

The country, which once had guaranteed employment for life, now struggled with unemployment, which affected young job seekers most significantly. Consumer confidence plummeted and the economy went into deflation. The BoJ tried to help by keeping interest rates at zero, and kept them there for a few years but, still, the recession continued. Land prices dropped 15 per cent in some of Japan’s largest cities, which meant that homeowners owed more than their homes were worth.

During the 2000s, the government tried to improve business confidence through huge stimulus packages and invested in building infrastructure, such as roads and bridges, and jobs were created. These measures helped to boost the economy but were not powerful enough to pull the economy out of recession, while it simply increased debts and added to the country’s deficit in the long run. What finally helped was the quantitative easing programme which the BoJ started in 2001, lasting until 2006. By 2003, GDP reached a 2 per cent growth and exports grew once again, but this upswing in growth was short-lived.

The 2008 global financial crisis began with the asset bubble which was created by the US housing market. It was fuelled by toxic subprime mortgages. When the US Federal Reserve increased interest rates, many borrowers whose loans were tied to adjustable-rate mortgages quickly saw their monthly bills shoot up, and millions of homeowners defaulted.

Earlier, banks profited by pooling these loans into mortgage-backed securities, which were traded by investment banks globally. The deepening of the mortgage crisis had an adverse effect on the securities markets. The bank witnessed a credit crunch and investment banks such as Lehman Brothers declared insolvency. The crisis affected global financial markets and the global economy moved into deep recession. The US Federal Reserve reduced Fed funds rate to zero per cent from 2008 to 2014. It also implemented a series of quantitative easing measures. The US Congress approved a US$700 billion relief programme to provide emergency aid to banks as well as underwater borrowers (Siddiqui, 2022).

Productivity growth is important for a country’s future growth. In Japan, labour productivity growth has been very slow in recent decades compared to labour productivity growth in G7 countries. Since Japan’s labour force is shrinking, the country needs to attain high labour productivity growth that is sufficient to more than offset the decline in its labour force to ensure increased prosperity in the coming years.

During the stagnation, the country’s industrial production dropped considerably at the time of the global financial crisis as global demand for advanced manufacturing, particularly electronics and motor vehicles, fell sharply. Industrial production also fell in the aftermath of the Tohoku tsunami. More recently, industrial production began to gradually increase, but recovery in Japan has been weak for many reasons, including the shifting of production and increased competition from other Asian countries, including China.

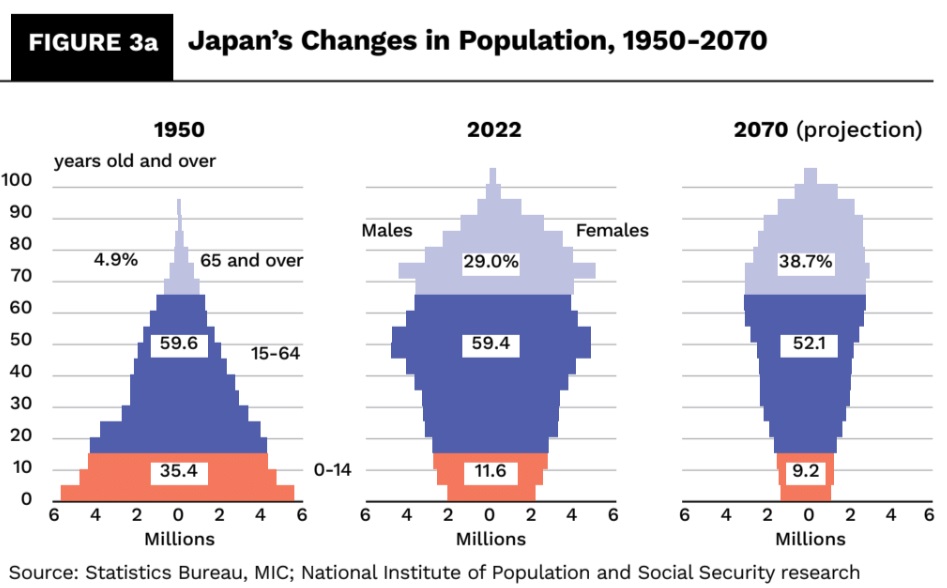

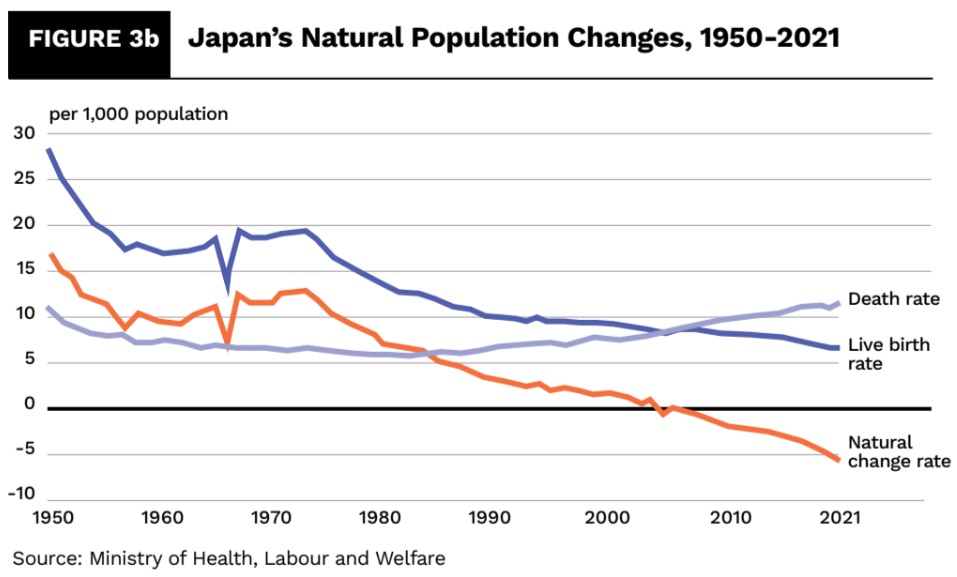

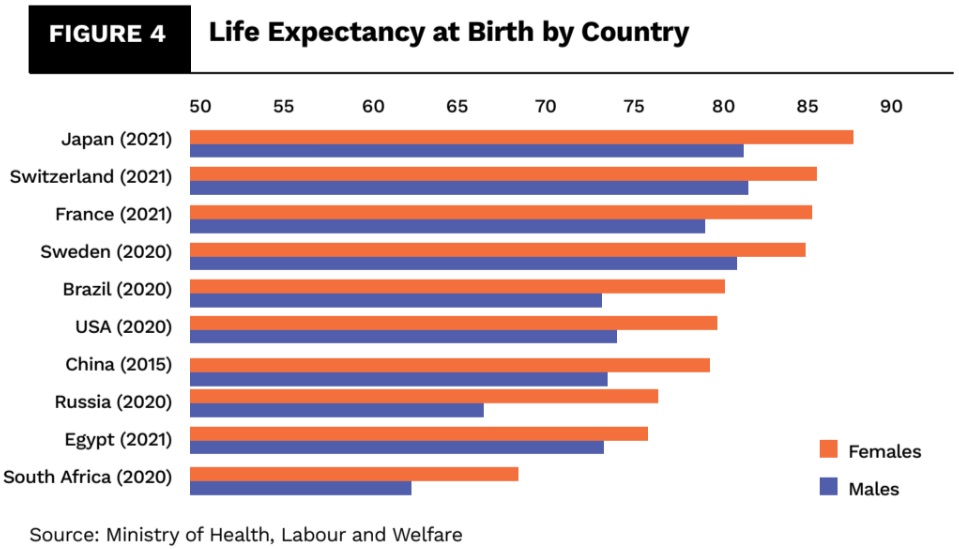

The other most important development is that the population of Japan is declining. At its peak in 2009, the country’s population was 127 million. It is projected that by 2050 Japan’s population will decline and reach 108 million (see figure 3). Moreover, life expectancy has risen sharply since 1950 and its population is also ageing rapidly (see figure 4). This is combined with low fertility rates, and recently Japan has opened limited immigration, which is due to increased demand for labour, especially in social services and care homes. With an ageing and declining population, the country’s working-age population is likely to decrease in the coming years. The fertility rate (i.e., births per woman) in Japan is one of the lowest among advanced countries. Japan’s fertility rate is less than 1.4 per woman as of 2018, whereas in the US the rate is around 1.8 and, in France, it is nearly 2.0. The number of foreign-born persons as a share of the country’s population is also very low, reflecting the lack of openness to immigration. Less than 2.0 per cent of the total population in Japan is foreign-born, whereas in the US it is about 14.5 per cent, and in Australia, it is much higher, at 28 per cent of the total population.

The demographic crisis of a falling population, which has formed an ageing society with fewer children, has deepened in Japan in recent decades. Japan’s ageing population is already affecting nearly every aspect of society (see figure 4). More than half of all municipalities are designated as depopulated districts, schools are closing, and more than 1.2 million small businesses have owners aged about 70 with no successor.

The demographic crisis of a falling population, which has formed an ageing society with fewer children, has deepened in Japan in recent decades. Japan’s ageing population is already affecting nearly every aspect of society (see figure 4). More than half of all municipalities are designated as depopulated districts, schools are closing, and more than 1.2 million small businesses have owners aged about 70 with no successor.

It signifies a crisis of the reproduction of human population as a basic foundation for socioeconomic life. As Itoh (2021) argues, “This crisis is paradoxically a historical result of the success of the capitalist market economy that has decomposed communal human relations more and more in mobilising both human labour power as an individual commodity, as well as individual consumers to expand and deepen markets. Especially under neoliberalism’s ICT automation systems, this trend has widely increased the irregular and unstable employment of younger generations and has also facilitated individual consumption styles. As a result, marriage and child-rearing have become delayed, with the resulting trend of increasing the number of single people among the younger generations. It thus represents another important contemporary appearance of the deepening contradiction of the commodification of labour power.” The number of retired people has risen sharply and has increased the burden of younger working generations to support social costs for both public medical care and pensions for retired senior generations. While 7.7 working people could be expected on average to support one senior retired person in 1975, 2.2 working people must do so by 2010, and less than two people must bear the social costs of one senior person after 2022. This perspective has deepened the sense of disenchantment among younger generations and has worked to promote this demographic crisis as an issue that has been difficult to solve in the present socioeconomic order (Itoh, 2021).

According to Desai (2022), the US-backed neoliberal financial capitalism was imposed globally from 1990 as the US came to a leading position in the unipolar world. Given the minimal state role under neoliberalism, the monetary policy option was left as the only instrument with which countries could try to restore growth. In 1996, the BoJ tried to keep interest rates low to stimulate the economy, as Desai notes: “Since 1996 short-term rates have been well under 1 per cent and have now slipped to a quarter of 1 per cent. Yet these extremely low rates were unable to prevent a slide into recession, let alone reverse the stagnation that has plagued the Japanese economy since 1992. … Japan is caught in a classic liquidity trap, where zero is not low enough” (Desai, 2022: 8). Desai argues that in the early period, competitive capitalism socialised labour between firms, but “later monopoly capitalism deepened the technical division of labour within them in vast productive apparatuses. Thereafter, rather than any vigorous virtues of competition it ever had, capitalism increasingly manifested the decadent and rentier vices of monopoly, diverting resources from production and suppressing competition” (Desai, 2022: 12). However, the declining power of trade unions and the development of monopolistic competition gave way to brand competition and in the rivalry of the market, expensive persuasion and advertising became an important tool, instead of price competition. These are factors that are seen as vital for expanding markets, rather than advancing in technical progress and increasing productivity.

Under competitive conditions, obsolete technologies were scrapped in industry but, under monopoly capitalism, firms postpone new investments in technology and firm expansion until the unprecedented value of the old machine is at least covered by the economies of new technologies. This means that progress will be slowed down (Desai, 2022).

According to Itoh (2021), with the sharp rise in primary commodities in the mid-1970s and again in the late 1980s, the advanced economies saw rising inflation, which led to higher wage demands in the process of deriving vicious inflation and also squeezed profit rates, which was a fundamental factor behind the crisis. The acute inflation was destructive in itself. It was, however, not caused just by oversupply of money and credit, but pushed up by sharp rises in wages and primary products due to over-accumulation of capital. Other Marxists on the crisis in capitalist economies point towards falling aggregate demand for commodity products, known as the underconsumption crisis theory.

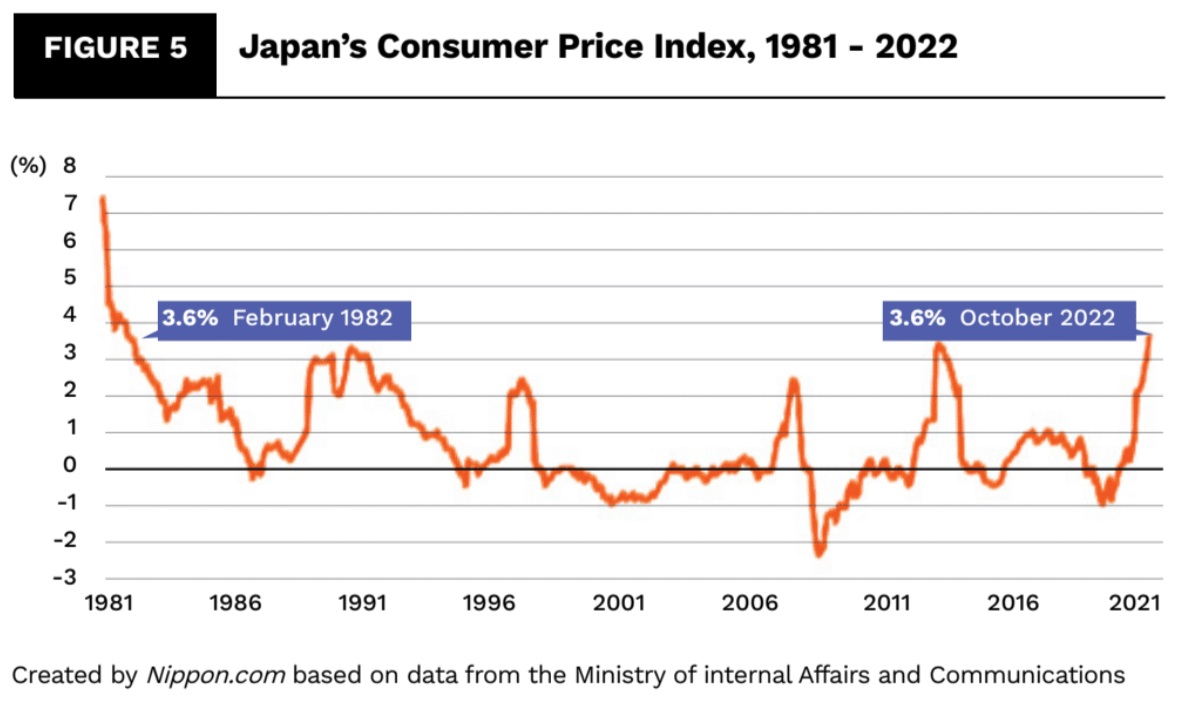

In the 1980s, Keynesian fiscal and monetary remedies proved ineffective against this inflationary crisis and “stagflation” (i.e., both stagnation and inflation). Then, neoliberalism became a new mantra, especially after Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in the UK in 1979. Neoliberalism is based on competitive market policy as means to realise the rational economic order by reducing government regulation (Siddiqui, 2019b). Japan’s inflation trends from 1990 to 2022 are shown in figure 5. In Japan, such neoliberal policies have been implemented widely since 1981 (Siddiqui, 1995). It promoted the restructuring of the capitalist system of accumulation especially to economise in wage costs using new technologies, to strengthen competitive power in the world market against the soaring yen in the late 1980s (Siddiqui, 2023a).

From the 1990s, the impact of information and communication technologies (ICT) in capitalist economies also promoted changes in the capitalist market. For example, especially as ICT automation spread broadly to factories, shops, and offices, flexibly adjustable forms of irregular employment, such as cheap part-timers, easily increased the mobilisation of more and more female workers, thus reforming the labour market into a competitive, individualistic market with reduced social protections. The trade unions’ social role of stabilising employment and improving working conditions was weakened. Neoliberal labour policies promoted such trends by removing restrictions to permit the widespread use of irregular employment in various types of jobs. The privatisation of three state-owned enterprises in 1985 — Japanese National Railways (JNR), Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT), and Japan Tobacco and Salt — was a heavy blow to the traditionally militant trade unions.

From the 1990s, the impact of information and communication technologies (ICT) in capitalist economies also promoted changes in the capitalist market. For example, especially as ICT automation spread broadly to factories, shops, and offices, flexibly adjustable forms of irregular employment, such as cheap part-timers, easily increased the mobilisation of more and more female workers, thus reforming the labour market into a competitive, individualistic market with reduced social protections. The trade unions’ social role of stabilising employment and improving working conditions was weakened. Neoliberal labour policies promoted such trends by removing restrictions to permit the widespread use of irregular employment in various types of jobs. The privatisation of three state-owned enterprises in 1985 — Japanese National Railways (JNR), Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT), and Japan Tobacco and Salt — was a heavy blow to the traditionally militant trade unions.

The prolonged stagnation could not be fully resolved even in the recovery phase of 2002-7. As the recovery in Japan depended mainly on increased exports induced by the consumption (and housing) boom in the United States and in other economies, Japanese growth rates remained at a low level of just 0.9 per cent from 1991 to 2019. The subprime crisis in 2007-8, originating in the US, and the subsequent sovereign crisis in Europe, especially damaged the Japanese economy among the major advanced countries. This was because the preceding feeble recovery in Japan tended to depend only on expanded demand from abroad, leaving the deflationary spiral in the domestic economy structurally unresolved with deteriorating working conditions. The lost decade of the Japanese economy continued to last three decades with zero growth. Under neoliberalism, Japan saw a rise in speculative investment in real estate, leading to the collapse of the stock market in 1990 and initiating the lost decades. During this prolonged stagnation, Japanese capitalism also exhibited a rise in inequality in the distribution of wealth and income since the 1980s, accompanied by deterioration of working conditions with lowered real wages and rising unemployment, combined with a weakened role of trade unions.

Moreover, the fiscal crisis of the state deepened, accompanied by neoliberal aims of privatising public enterprises, reducing state support for education, medical care, and pension schemes to reduce the public debt, although this was not achieved. Reductions in corporate tax, marginal rates of income tax, and inheritance tax favoured the rich. On the other hand, the costs of welfare policies to be paid for senior citizens had steadily increased. As a result, since neoliberalism, the outstanding amount of Japanese state bonds continued to increase and is estimated to have reached 932 trillion yen by the end of 2020. The total public debt in addition to this amount of state bonds, plus the public bonds of local governments of around 200 trillion yen, amounts to 237.6 per cent of the GDP (estimated by the IMF), thus reaching by far the highest level among advanced countries.

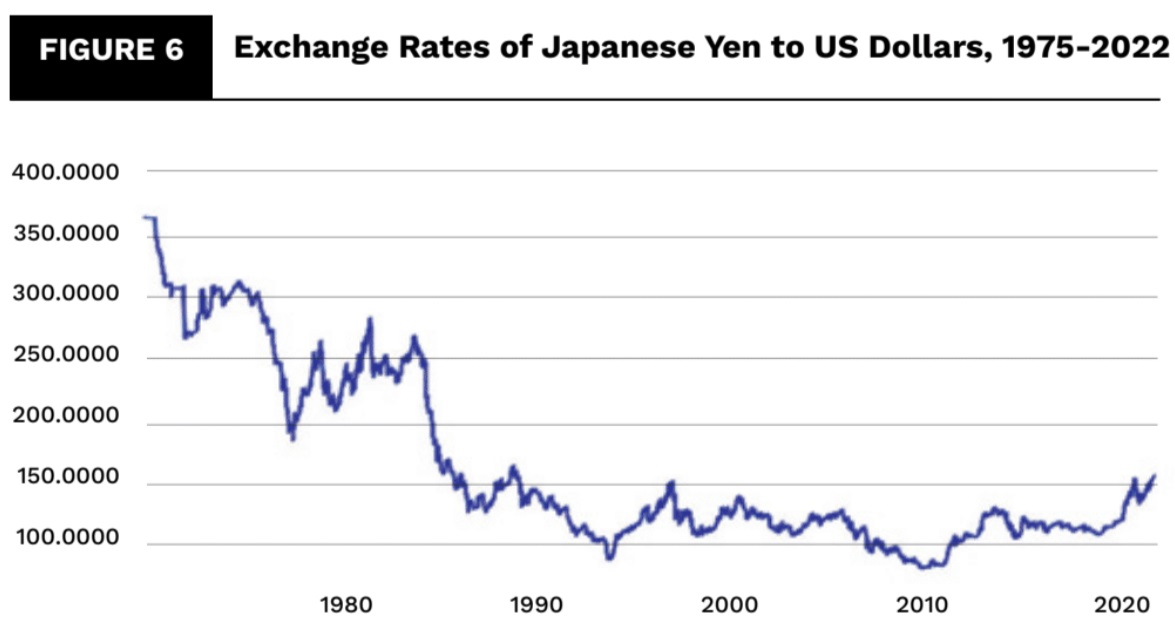

Japanese capitalism under neoliberal globalisation led to repetitive soaring yen exchange rates (as shown in figure 6) and reduced domestic manufacturing by relocating overseas, i.e., in Asia. As a result, workers in secondary industries such as manufacturing and construction, which used to form a central core industry of Japanese economic growth since the Meiji Restoration, peaked in 1992, and by 2019 it began to decrease widely by 6.28 million (28.6 per cent). Workers in services, including restaurants, hotels, transportation, medical services, and education steadily increased their proportion of total employment from less than 50 per cent in 1970 to more than 60 per cent in 1993, and since 2019, it has risen more than 70 per cent.

Conclusion

Real annual economic growth rates in Japanese capitalism have declined in the last three decades. In the period of high economic growth after the Second World War, in 1956-73, the Japanese average annual growth rate recorded 9.1 per cent. After this long and prosperous period, the Japanese economic growth rate fell to 4.2 per cent in the annual average between 1974 and 1990, which includes the first decade of neoliberalism. However, the decline of the growth rates was sharp but was still 1-2 per cent higher than in most of the other advanced economies in the 1980s, combined with the effect of a wide appreciation of the yen against the dollar, from 360 yen a dollar to around 150 yen a dollar in 1987.

Moreover, Japan has had the highest proportion of state debt against GDP among the major advanced economies. Changes in the Japanese government’s total debts for over 30 years are shown in figure 2. This puzzling paradox can be deciphered to a certain extent by observing two factors: the high savings rate of Japanese households, which has enabled Japan to absorb its cumulative state debt domestically; and the competitive strength of exporting industries, which has permitted Japan (thus far) to maintain a continuous trade surplus (Johnson, 1994).

Four decades of neoliberal capitalism in Japan have increased inequality in the distribution of wealth and income, namely by increasing unstable and lowly paid irregular workers beyond half among female wage workers, and over one-third of the total employees including male workers, all the while allowing capitalist firms to accumulate massive internal reserve funds (475 trillion yen in 2019) beyond the amount of the annual net national income as Itoh notes: “demographic stagnation, expanding economic inequality, globalisation and its effect on the suppression of real wages, rising costs of higher education, and the cumulative increase in public and private debts. A similar reduction of labour share in the process of increasing temporary and irregular workers seems to be the fundamental factor that has become common to advanced capitalist countries under neoliberalism, and that forms the trend of secular stagnation and decay.” He concludes, “Japanese capitalism, which was once regarded as a leading model for industrialising Asian countries in the flying geese theory until the 1980s, now seems to be presenting a rather reversed typical model for decaying advanced countries in the world” (Itoh, 2021: 311).

The study concludes that the structural crises in the Japanese economy have deepened just like in other advanced capitalist economies. Factors that have contributed to the reversal in growth that has resulted from the fiscal crisis and that has affected states that were caught in the subprime crisis are the decline in the state bonds of some European countries, along with similar dangers for the US. Japan’s exporting industries are losing their competitive power and profits as a result of the huge appreciation of the yen to less than 76 yen against the dollar, a historically unprecedented high (Siddiqui, 2023b).

For short-term solutions, Japan needs to raise productivity and effort should be made to further increase the female participation rate and narrow the male-female wage gap. The country needs to open for immigrants and to accept more foreign-born workers through immigration and such policy would address shortages of workers, mitigate skill gaps, and boost labour supply. Moreover, increased investment in the environment and green technology would boost living conditions. Trade unions’ wage bargaining should be encouraged, leading to higher consumption and demands. Japan needs to reconstruct cooperative communities and organisations at the grassroots level.

About the Author

Dr. Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

Dr. Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

References

- Desai, R. (2022) “Introduction: Japan’s Secular Stagnation and the American Mirror” Japanese Political Economy, 47(4): 281 – 302.

- Itoh, M. (2021) “Japanese capitalism in multiple crises”, Japanese Political Economy, 47 (4): 303-324.

- Itoh, M. (1990) The World Economic Crisis and Japanese Capitalism, London: Macmillan.

Johnson, C. (1994) Japan Who Governs: The Rise of Developmental State, New York: W.W. Norton & Company. - Johnson, C. (1982) MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975, Stanford: University of Stanford Press.

- Siddiqui, K. (2023a) “Marxian Analysis of Capitalism and Crises”, International Critical Thought, forthcoming.

- Siddiqui, K. (2023b). “De-dollarisation, Currency Wars, and the End of US Dollar Hegemony” The World Financial Review, August-September, pp.2 – 14

- Siddiqui, K. (2022) “Capitalism, Imperialism, and Crisis” The European Financial Review, June/July, pp.16 – 32.

- Siddiqui, K. (2019a) “The US Economy, Global Imbalances under Capitalism: A Critical Review” Istanbul Journal of Economics 69(2): 175 – 205, December.

- Siddiqui, K. (2019b). “Financialisation, Neoliberalism and Economic Crises in the Advanced Economies” The World Financial Review, May-June, pp.22-30.

- Siddiqui, K. (2015) “Political Economy of Japan’s Decades-Long Economic Stagnation” Equilibrium Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 10(4): 9-39.

- Siddiqui, K. (2009) “Japan’s Economic Crisis”, Research in Applied Economics 1(1): 1 – 25.

- Siddiqui, K. (2009) “Japan’s economic stagnation” Klassekampen (in Norwegian), November 3, Oslo, Norway.

- Siddiqui, K. (1995) “Political Economy of Japan”, The Nation, January 20.

The Economist (2021) “Japan’s Economy is Stronger than Many Realise”, December 11, London.