By Ulrike Schaede, University of California San Diego

On February 15, 2021, Japan’s Nikkei 225 index crossed the ¥30,000, for the first time in 31 years. Japan’s M&A market has recently grown into the world’s second largest, after the U.S.. Private equity deals have risen spectacularly. Underlying these developments is the ongoing business reinvention by Japan’s largest companies, which are repositioning to compete in highly specialized input materials and products. This reinvention has been quiet and steady, and it is now being recognized.

Why Reinvent?

The last time Japan’s stock market scored above 30,000 was in the middle of the “bubble economy”. That collapsed in 1991, costing three times Japan’s GDP in stock market and real estate corrections alone. Since then, most people have heard very little about Japan, other than of a banking crisis, stalling economic growth, persistent deflation persistent, and skyrocketing government debt.

For Japan’s largest companies, the mid-1990s also brought a huge competitive shock, with the rise of companies in South Korea and Taiwan, and then China, as high-quality mass-production assemblers. They eroded Japan’s competitive advantage in household and office electronics, as well as semiconductors. A completely new competitive dynamic began to emerge in North East Asia, and Japan’s corporates were at a loss in how to respond.

The globalization of supply chains also occurred around that time – and would eventually turn into Japan’s new opportunity. Advances in logistics and trade agreements allowed for the staging of the various steps of the production process in the most economically efficient location or country.

Moving Upstream

At the turn of the century, Japan’s leading CEOs began to realize that there was no money to be made competing head-on with China’s low-cost assembly prowess. The solution was to pivot away from end products and into the higher value-added components. Between the early aughts and 2020, Japan’s leading companies acquired new skills in innovative, advanced materials and deep tech-based components as well as production equipment. In a vast range of industries – ranging from carbon fiber and fine chemicals for electronics, sensors and vision technology, factory automation, to semiconductor packaging materials and testing equipment – Japanese companies now rank among the world’s leaders.

This reinvention – away from end products to input materials – has gone largely unnoticed. But even though there is no “Japan Inside” sticker on the final products, Japan is in our daily lives. Our cell phones, cars, cameras, computer screens, and everything smart in our homes is, with a very high probability, made with a set of advanced materials and production technologies from Japan.

For North East Asia, Japan’s emergence as the deep-tech anchor of the regional supply chains has brought interesting new power plays. The trade between Japan and China (incl Hong Kong) is roughly equal today. But, South Korea and Taiwan have a trade deficit with Japan, because they buy the critical materials and components to make parts. And China has a trade deficit with South Korea and Taiwan, because it needs those parts for the assembly of end product.

The Aggregate Niche Strategy

I have labeled Japan’s new dominance in these deep-tech, upstream materials, components, and equipment as the “aggregate niche strategy.” This has two dimensions: a large company play, and a country play. First, one large company may hold a leading global market share in critical input materials, components, machinery, etc., in a series of adjacent businesses. For example, chemical company JSR leads the world in photoresists (for semiconductor production), both in terms of quality and volume, as well as polarizer film and other advanced materials for LCD panels. In the aggregate, that makes JSR a critical global provider of fine chemicals for electronics, even though end consumers are unaware of this dominance.

Second, in some product markets, multiple Japanese companies occupy the global top ranks, creating a leadership position for Japan. To stay with the example above, JSR’s main global competitors in photoresists are also Japanese, such as TOK (Tokyo Ohka Kogyo) and Shin-Etsu Chemical. Similarly, for polarizing film, those companies are joined by Nitto and Fujifilm, among others. When a company such as Samsung develops a next generation semiconductor or cell phone screen, it is dependent on Japan for the super-high quality input materials needed to innovate at the technology frontier.

This story repeats across sectors. In a study of roughly 900 input and end products – from endoscopes and CMOS chips to batteries and robots – Japanese companies combine to a global market share exceeding 50 percent in about 500 categories, and 100 percent in over 50 products. On average, these global markets have a size of about $5 billion, which may not be that big. But in the aggregate, these niches add up very nicely. [1]

Note that the makers of these products are among Japan’s largest companies. This is not a story about small companies, or of hidden pockets of innovation. Rather, it represents the new face of Japan’s global competitive thrust. Their strategy is to stay ahead of China by operating at the technology frontier, in difficult-to-make and difficult-to-imitate technologies that earn higher margins, require fewer people and are based on deep and often tacit knowledge.

Corporate Japan’s Big Diet

Japan’s largest companies have an understandable reason for why it took them two decades to morph from brand-leading household electronics to anonymous designers of deep-tech inputs: They were not originally built for this! Japan’s postwar strategies centered around very large, highly diversified conglomerates whose competitive advantage was based on size. The new aggregate niche strategy, in contrast, is a focused, nimble approach to winning through speed and innovation.

What is more, competing at the technology frontier means that they need to produce breakthrough innovation, which is very different from the incremental innovation and commercialization of the past. Thus, a new mindset and corporate culture are needed, to steer employees and organizations toward more risk-taking, creative approaches to R&D.

To tackle this challenge, companies had to first go on a diet. Slimming down had begun in the late 1990s, when the excessive and often ill-advised diversification of the bubble period was unraveled. But that first wave of “choose and focus” meant getting rid of mostly extraneous, non-performing subsidiaries. It was not until the 2010s that Japan’s largest companies began to truly reinvent themselves.

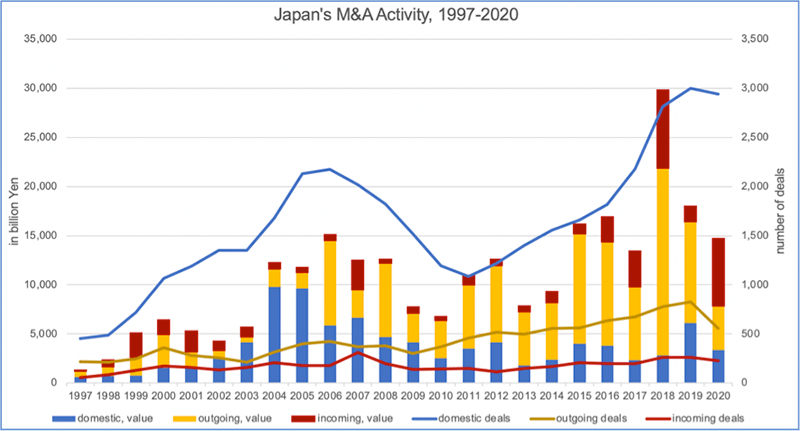

Exhibit : Japan M&A Deals, by Value (stacked, left scale) and in Number of Deals (lines, right scale)

The Pivot

Exhibit 1 combines data on M&A value (left-hand scale) and deals (right-hand scale), to show the two waves of repositioning. In 2018, total deals reached 4,000 in number and ¥ 30 trillion (roughly $300 billion). The current second wave represents a true pivot into new business areas for competition in the future. It consists of two simultaneous steps: to leave behind yesterday’s core, and to expand forward into a new, global corporate identity.

The forward move is seen in the outgoing deals, which are large and growing in value (the yellow line and stacked bar). Japan’s best-known global acquisitions of late include Suntory of Jim Beam (2014, $16 billion), Softbank and ARM (2016, at $31.4 billion), Takeda and Shire (2019, at $62 billion). These headline grabbers obscure the more than 600 annual, large acquisitions, from beer to banking and insurance to engineering. These global expansions reflect a search for new markets with young and thirsty consumers, and constitute a growing global reach of Japan for new technologies and industrial bases.

The second move, “leave the old behind”, has a domestic and a global dimension. The domestic deals (in blue) are frequent though relatively small in dollar terms. They include a growing wave of domestic consolidation, as well as a fast-growing domestic private equity play around small firm successions and turnarounds.

The incoming deals, in contrast, are dominated by foreign PE funds that are sensing an opportunity as Japan’s conglomerates carve out their core pieces. They are fewer in number but much larger in size. The largest PE deal value on record was the 2018 sale of Toshiba Memory to a consortium led by Bain Capital for $18 billion.

Case in Point: The Hitachi Co., Ltd. Pivot

Illustrating this new global interest in Japanese PE is Hitachi’s recent move. Between 2016 and 2020, Hitachi divested or carved-out at least 12 large business units or subsidiaries, including its finance, power tools, forklifts, construction machinery, diagnostic imaging, and overseas appliances businesses. On top of that, it carved out Hitachi Chemical and Hitachi Metals, two of its erstwhile three main pillars. None of these deals were somebody’s else garbage; they all were highly functional and profitable undertakings. In that same period, Hitachi announced the acquisition, fully or partially, of businesses that increase the company’s profile in smart city and social innovation infrastructure, including ABB Power Grids and a spin-in of Hitachi High-Technologies.[2] The declared goal is to compete in the digital disruption as an advanced data solution and smart infrastructure company.

These moves had a huge impact. First, the high-quality carve-outs attracted yet more PE interest to Japan. And, they took away any remaining excuses by Japan’s laggards for how they were somehow too big or too old to pivot. The new “choose-and-focus” movement is bound to continue. While the 2020/21 pandemic may have cooled the excitement temporarily, Japan experts expect the upward trend to resume in the new future.[3]

Corporate Culture Change

Slimming down and pivoting alone will not position Japan’s leading companies at the technology frontier. To stay abreast of its up-and-coming Asian rivals, they have to be leaders in difficult-to-make and difficult-to-imitate deep-tech areas. In addition to being agile in placing strategic technology bets, this requires a new mindset about risk-taking and innovation. In short, the move from incremental to breakthrough innovation necessitates a culture shift away from “make no mistake” and toward “break it-fix it”.

This internal change is only now just beginning, and it is by far the most challenging part of the reinvention. Many CEOs struggle, not just with laying out a vision but overcoming resistance at the mid-management level. What is more, Japan’s so-called “tight culture” – i.e., a high degree of consensus on the norms of appropriate behavior and low tolerance for deviant behavior – requires a particular approach to change management. This may look overly slow and regimented to somebody from a “loose culture” setting, such as the Anglo-Saxons.[4] Indeed, it is often said that changing the culture of a Japanese company is like turning a cargo ship: it takes a very long time and leaves huge turbulence in its wake. But once turned, it is soon ready to move ahead at full steam.

Japan’s reinventing companies are currently in the middle of making these huge turns. After years of preparing, some are already coming out of it and are moving ahead. Not all will be successful. Some are stuck in their old patterns and are not even trying. But at the top end, exciting change is happening in Japan. Ignore it at your own peril.

About the Author

Ulrike Schaede is Professor of Japanese business, at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy (GPS). Her latest book, “The Business Reinvention of Japan” (Stanford UP), analyzes the ongoing transformation of Japan’s leading firms, as well as changes in Japan’s  corporate governance, management and employment systems.

corporate governance, management and employment systems.

References

- [1] For data and a more detailed explication of these concepts, please see Ulrike Schaede, “The Business Reinvention of Japan” (Stanford UP, 2020).

- [2] Based on corporate website, news articles, https://www.hitachi.com/New/cnews/

- [3] “Bain Capital Boosts Japan Staff by 25% as Competition Grows”, Bloomberg, Feb 7, 2021.

- [4] “Tight-loose” theory is a new framework from psychology that is quite powerful in understanding global management challenges. For the general treatise, see Michele Gelfand, “Rule Makers, Rule Breakers”, Scribner 2018. For the application to Japan, see Schaede, “The Business Reinvention of Japan”, Stanford UP 2020.