This is the second part of Dr. Kalim Siddiqui’s analysis of India’s agricultural liberalization. This segment delves into the impacts of neoliberal reforms on food security, food sovereignty, and sustainable development, emphasizing the need for public investment and support for small farmers to achieve a resilient and equitable agricultural future. Read the first part here.

Food Security, Food Sovereignty and Sustainable Development

The issues of food security, food sovereignty, and sustainable development are critically important for a densely populated country like India. The interplay between these factors influences not only the well-being of its population but also its role in the global food system.

Food security is essential for ensuring that all people have access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs for an active and healthy life. The FAO defines food security as “the availability at all times of adequate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices” (Patel, 2009). In India, food security is compromised by several factors:

- Purchasing Power: The decreasing purchasing power of the poor has led to increased food insecurity. Despite availability, many cannot afford adequate nutrition.

- Public Distribution System (PDS): The effectiveness of the PDS has been compromised by inefficiencies and corruption. The system’s ability to provide affordable food to those in need has been undermined.

- Government Support: The reduction in government spending on rural development, including health, education, and infrastructure, has exacerbated food insecurity. Programs designed to support the poor, such as food-for-work initiatives, have also seen cuts.

- Regional Disparities: Food security varies significantly across India. States with low agricultural growth like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa exhibit low levels of food security. Conversely, higher-growth states like Gujarat and Rajasthan still experience high levels of food insecurity among the rural population.

Food sovereignty refers to the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods. It emphasizes the need for local control over food systems and policies. For India, food sovereignty is crucial for several reasons:

- Global Price Volatility: The global food price crisis, particularly evident between 2007 and 2008, highlighted the vulnerability of countries heavily reliant on food imports. For instance, while world rice prices surged, China’s self-sufficiency shielded it from severe impacts. In contrast, India’s high dependence on rice imports led to significant price increases domestically (Bernstein, 2014).

- Policy Pressure: Food sovereignty protects countries from external pressures that could force them into policy changes detrimental to their own food systems. For example, during crises like the Ukraine war, countries with strong food sovereignty can resist external pressures that might otherwise lead to adverse policy shifts.

- Local Control: Emphasizing food sovereignty helps resist the dominance of large agribusinesses and ensures that local agricultural practices and food systems are preserved. This is crucial for maintaining agricultural diversity and sustainable farming practices.

Sustainable development in agriculture aims to balance economic growth with environmental and social considerations. In the context of India:

- Environmental Impact: The Green Revolution’s focus on high-yielding varieties and chemical inputs led to soil degradation, reduced soil fertility, and other environmental issues (Walker, 2008). Sustainable agricultural practices are needed to address these concerns and ensure long-term productivity.

- Capital Investment: Public investment in agriculture has stagnated, and private investment has not filled the gap. Historically, public investment in irrigation and other infrastructure supported agricultural growth, but this support has waned (Bernstein, 2014). Reinvesting in such public goods is critical for sustainable development.

- Rural Employment: The failure to create sufficient jobs in rural areas and the shift to capital-intensive crops have led to higher rural unemployment and economic distress. Sustainable development should focus on creating diverse employment opportunities and supporting small and medium farmers.

- Globalization and Local Impact: While globalization offers opportunities, it also presents challenges. The influx of foreign capital and the integration into global markets must be managed carefully to protect local industries and agriculture.

India’s experience with food security, food sovereignty, and sustainable development underscores the need for a balanced approach. Policymakers must prioritize:

- Strengthening Food Security: By improving the efficiency of the PDS, increasing support for rural development, and addressing regional disparities.

- Ensuring Food Sovereignty: To safeguard local agricultural systems and resist external pressures.

- Promoting Sustainable Development: Through responsible investment, environmental stewardship, and diversified rural employment opportunities.

Addressing these issues comprehensively will not only improve the well-being of India’s population but also enhance its resilience in the face of global economic fluctuations and environmental challenges.

In the most populated country like India, it is very important to give greater emphasis on food security because India’s food demands could have a large impact on world food prices. And food sovereignty is also important so that the rich countries do not pressurise for policy change in return for food during the crisis as we have seen more recently during the Ukraine war as indicated in Figure 4.

For example, the extraordinary world price fluctuations in food commodities increased by around three and a half times between January 2007 and June 2008. However, during this period the price hike in some large economies like India and China had dealt better compared to many Sub-Saharan food-importing countries. The rice prices, for example, increased by 30 % over this period, despite the high world price volatility. Also, China’s food self-sufficiency in food had helped the country to insulate its population from the effects of high world prices in the main food commodity prices. In contrast to this, Indian rice is also staple food, and a large proportion of the population was adversely affected by the increased price of rice in 2008. However, after the fall in global food prices, the retail price of rice in Indian markets was still 60 % higher in May 2009 than in January 2007 (Bernstein, 2014).

The main Reasons for Food Insecurity in India

1. Decrease in Purchasing Power:

-

- Impact on Food Access: The decrease in purchasing power among the poor has made it increasingly difficult for them to afford sufficient and nutritious food. This economic strain significantly affects their ability to meet basic food needs.

- Income Inequality: Rising income inequality has further exacerbated food insecurity, with the wealth gap preventing equitable access to resources.

2. Insufficient Functioning of the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS):

-

- Implementation Issues: The TPDS, meant to provide subsidized food to the poor, has suffered from inefficiencies, corruption, and poor management. This has undermined its effectiveness in ensuring food access.

- Distribution Gaps: Failures in distribution mechanisms have meant that food does not always reach those who need it most.

3. Decline in Government Support and Public Spending:

-

- Cuts in Essential Services: The reduction in public investment in rural development projects, including health, education, and infrastructure, has diminished the safety nets available to the poor. Programs such as food-for-work schemes have also seen cuts.

- Impact on Rural Development: The lack of investment in critical areas has hindered overall development and reduced the effectiveness of poverty alleviation strategies.

4. Regional Disparities:

-

- Low Agricultural-Growth States: States like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa, with historically low agricultural growth, experience higher levels of food insecurity due to inadequate infrastructure and support.

- High Food Insecurity in High-Growth States: Even states with higher agricultural growth, such as Gujarat and Rajasthan, face significant food insecurity among their rural populations, indicating that growth does not always translate into improved food security.

5. Impact of Neoliberal Reforms:

-

- Reduced Rural Credit: Neoliberal reforms have led to a reduction in institutional credit for agriculture, making it harder for small and medium farmers to invest in and sustain their operations.

- Dismantling of Public Systems: The dismantling of the public distribution system and cuts in essential services have compounded the challenges faced by the rural poor.

- Trickle-Down Economics: The reliance on a ‘trickle-down’ approach, which assumes that benefits to the wealthy and business sectors will eventually benefit all, has failed to address the needs of the poor effectively. Instead, it has contributed to increased socio-economic inequalities and narrow sectoral growth

Figure 4: World Food Prices.

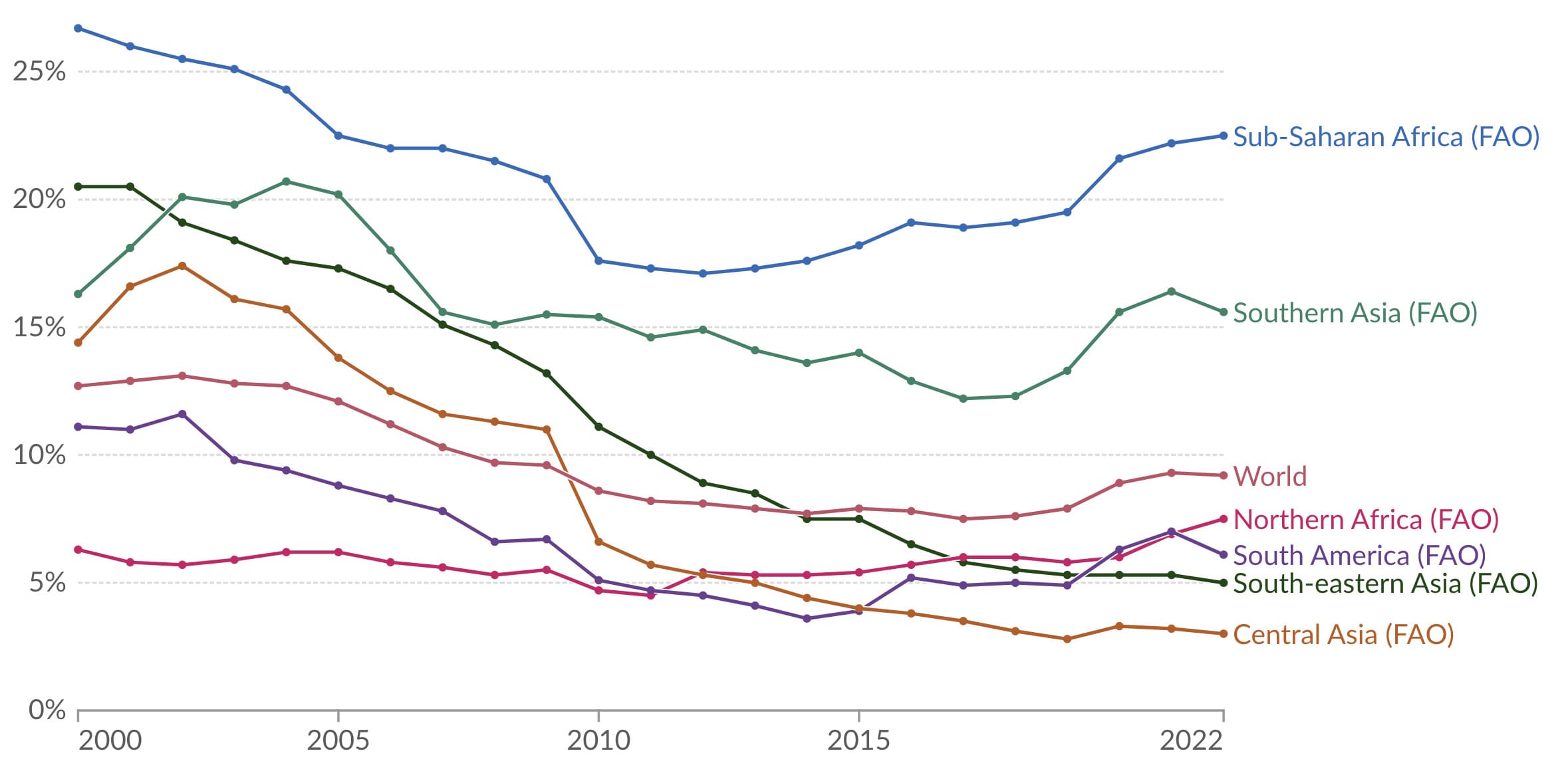

Figure 5: Share of Population with Severe Food Insecurity, 2014 to 2020.

The definition of food sovereignty was elaborated by World Forum for Food Sovereignty in Nyéléni, Mali: “Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute, and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies, rather than the demands of markets and corporations. It offers a strategy to resist and dismantle the current corporate and food regime…. It depends on the interests and inclusion of the next generation. Food sovereignty prioritises local and national economies and markets and empowers peasants and family farmer-driven agriculture. It ensures …. the right to use and manage lands….” (Cited in Patel, 2009: 673-4)

In 1991, in the face, a rising foreign debt crisis and balance of payments India decided to accept the ‘economic liberalisation’ policy and agreed to dismantle the ‘license raj’ system of tight controls and permits placed since the 1950s. The neoliberal policy took the form of a ‘structural adjustment’ programme imposed by the IMF and World Bank. The neoliberal reforms included deregulation, privatisation, and devaluation of the domestic currency. Soon after, the inflows of foreign capital rose sharply, but a large proportion went to real estate, financial sector, and services, rather than manufacturing or agriculture. As Bhaduri notes: “the Fiscal and monetary policies of the government need to comply with the interests of financial markets. …. Since the private banks and financial institutions usually take their lead from the IMF and the World Bank, this bestows on these multilateral agencies considerable power over the formulation of government policies. However, the burden of such policies is borne largely by the poor… Inequality and distress grow as the state rolls back public expenditure in social services like basic health, education, and public distribution and neglect the poor, while the ‘discipline’ imposed by the financial markets serves the rich and the corporations” (Cited in Walker, 2008: 562).

The PDS (public distribution system) was introduced in the mid-1960 to help the poor people, but after the neoliberal reform, the government is under pressure to remove food subsidies. Through the PDS system foodgrains were moved from food surplus states to food deficit states. The decline of cheap credits and privatisation of electricity resulted in a massive increase in electricity prices which were subsidised before. The public funds available for irrigation projects were also cut down, which adversely affected land productivity.

The World Bank and IMF pressurised India to follow their rules that ‘governments should not sell at prices other than global prices’, in response to this the government targeted PDS food subsidy by dividing the population into two groups – those grouped as lying ‘above’ and ‘below’ poverty line. This policy excluded millions of poor people from the list to receive essential commodities at affordable prices. The data shows that from 1992 to 2010, India experienced declining rates of growth in yields per hectare for both food grains and non-food grains. The output growth of agriculture was only 2.2 % for the same period. This was much lower than in the 1980s when agricultural growth was around 3.4 % per annum. Furthermore, growth rates for cereals were, in fact, negative averaging -0.11 % and -0.31 % respectively.

Large farmers have diversified their source of income e.g., real estate, trading, urban property etc. On the other hand, small farmers and agriculture workers, who have been forced to migrate under ‘distress’ to towns, are mostly employed in the informal sector on low wages and insecure jobs. Moreover, there is the diversion of farmland real estate and industrial development, which means less land is available for cultivation. Walker (2008: 579) argues: “Although the rural workforce has continued to grow – rising from 191 million in 1993-94 to 257 million in 2004-05 – employment growth in agriculture has fallen to virtually zero since the 1980s… Since the growth rate of agriculture is lower than the growth rates of both workforce in agriculture and rural population., with only limited employment outside agriculture, the clear implication, as the Report of Agriculture puts it, is that ‘per capita income in agriculture is declining’…”

To achieve sustainable development of the economy, the agriculture sector should play a crucial role. The long-term growth strategy must not ignore the agriculture sector. There is doubt about the feasibility of export-led growth for a country like India. Overall growth could be achieved by a substantial increase in public investment in areas such as irrigation, power, rural infrastructure, and easy access of formal credits. These measures could lead to an increase in agricultural productivity and a rise in farmers’ income and the expansion of domestic demand for industrial goods.

Most of India’s population continues to depend heavily on the agricultural sector for income. More than two-thirds of the population (nearly 800 million) lives in rural areas and to a large extent their livelihoods depend on the income and performance they produce. Since the 2000s we have seen a decline in rural employment and incomes, which resulted in a lowering of aggregate demands. There are various reasons for the agrarian crisis including changing climate and the uncertainties associated with the monsoons and by July 2001 quantitative restrictions were removed on imports. This means earlier protection through high tariffs on agricultural imports has been taken away and as a result, cheap imports of food from developed countries rose sharply.

In fact, as the agriculture sector began a downward spiral globally in the late 1990s, most of the developed countries kept subsidising their farmers, which enable them to sell food grain at competitive prices on the global market. However, according to the WTO rule, the Aggregate Measure of Support (AMS) reduction for a country is not commodity specific, which has allowed the developed countries to keep on supporting some commodities, while still meeting WTO’s reduction commitments. Moreover, most commodities are heavily subsidised by developed countries that are also produced and exported by developing countries like India. India produces surplus commodities like wheat, coarse cereals, dairy, beef, and sugar and these products accounted for over 87 % share of the total value of export subsidies for all products.

Conclusion

Agriculture’s share in India’s economy has progressively declined, while higher growth rates of the industrial and services sectors did not create enough jobs to make any dent in rural unemployment. The sector’s importance in India’s economic and social fabric goes well beyond this indicator. Nearly three-quarters of India’s families depend on rural incomes and most of India’s poor (some 770 million people or about 70 %) are found in rural areas. And nearly two-thirds of India’s workforce is still dependent on agriculture, the persistence of poverty and food insecurity in rural areas has resulted in a rise in migration and urbanisation, which has joined the “informal sector” in the labour markets. (Siddiqui, 2024)

In the agriculture sector, since the neoliberal reforms were introduced, government spending had been reduced drastically. The post-reform crisis seems to be not only in terms of declining growth rates in the agriculture sector compared to the pre-reform period, declining per capita food availability, and stagnating investment but also in terms of slowing down productivity and yield. Thus, reducing rural poverty and food sovereignty via agricultural development should be a major concern but seems to have been overlooked by the government. India’s economic liberalisation has had a profound impact on its agricultural sector, driving significant changes in trade policies, subsidies, investment, and technology adoption. However, the transition has been complex, with benefits and challenges unevenly distributed across different segments of the farming community. The political economy of agriculture in India remains a contested space, shaped by the ongoing struggle between the forces of liberalisation and the need to protect the livelihoods of millions of farmers.

The study finds that Indian agriculture is overburdened in the sense that a very high proportion of the population is dependent on this sector, while it has low productivity and low capital investment. It seems that the agriculture sector a has much greater impact on reducing poverty and improving food security than other sectors of the economy. Therefore, public investment is important as it played a positive role in the pre-reform period. Public investment in land and water management seems to be crucial for improving the agriculture sector in the long-term growth and viability in India.

The challenge of food security requires an ability to deal with increasing food shortages of ever-expanding population growth in India. The adoption of neoliberal policy resulted in agriculture stagnation, declining food consumption among the rural poor, and a rise in migration to cities.

The pandemic created food shortages, price rose sharpy and demonstrated the urgency of food security and food sovereignty and also for transition to a more ecologically sustainable and resilient food system. We find that the main determinant of food insecurity in India at present is the shrinking of the agrarian sector and the reduction in policies to combat rural poverty. It is clear now that effective government intervention to support foodgrain price stability requires fiscal intervention, which is not possible under the neoliberal policy framework. This seems to be an important barrier to contain food prices in many developing countries.

Developing countries need to advocate for fair trade policies and reforms within international trade agreements. Ensuring that global trade rules accommodate the needs of developing countries and reduce the disparity in subsidies is essential for creating a more balanced global market.

India’s agrarian crisis is a multifaceted issue involving domestic challenges and international trade dynamics. Addressing the crisis requires a comprehensive approach that includes policy reforms, investment in rural infrastructure, and a strategic focus on sustainable agricultural practices. Additionally, engaging in global trade discussions to ensure fair treatment for developing countries will be crucial for creating a more equitable and resilient agricultural sector.

The study recommends that for successful inclusive growth, agricultural growth is a prerequisite. It is important to implement land reforms, improve institutional credits and increase public investments in rural infrastructure, especially to assist small and marginal farmers and to diversify the rural economy. Until a level playing field is created across the world, otherwise trade liberalisation in agriculture will simply prop up developed countries’ farmers at the expense of farmers in developing countries like India. Addressing the agrarian crisis requires a re-evaluation of both domestic and international policies. Protecting vulnerable sectors, enhancing support for farmers, and ensuring fair trade practices are crucial for mitigating the impact of global trade dynamics. Emphasizing food sovereignty, investing in sustainable agricultural practices, and supporting rural development initiatives can help build resilience in the agricultural sector and improve food security.

About the Author

Dr Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

References

- Bernstein, H. (2014). “Food Sovereignty via the Peasant Way: A sceptical way”, Journal of Peasant Studies, pp.1-33.

- Datt, G., Ravallion, M. and Murqai, R. (2019) Poverty and Growth in India over Six Decades, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 102(1): 4-27.

- Dhar, B. (2023). “WTO Agreement on Agriculture: Worsening India’s Agrarian Crisis”, Indian Economic Journal, January.

- https://doi.org/10.1177/00194662221146638

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation). (2022). India at a Glance, Rome: FAO. https://www.fao.org/india/fao-in-india/india-at-a-glance/en/

- Ghosh, J. (2010) “The Political Economy of Hunger in 21st Century”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. XIV (44), October 30, pp. 33-38, Mumbai.

- Government of India, (various issues) Economic Survey, New Delhi: Ministry of Finance, (www.indiastats.com)

- Patel, R. (2009) “Grassroots Voices: What does food sovereignty look like?” Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(3): 663-706.

- Patnaik, Utsa (2003) “Global Capitalism, Deflation, and Agrarian Crisis in Developing Countries” Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 3 (1-2), pp. 33-66.

- Siddiqui, K. (1991) “India’s Green Revolution and Rural Poor”, Bergens Tidende, (in Norwegian) June 11, Bergen, Norway.

- Siddiqui, K. (1998) “The Export of Agricultural Commodities, Poverty and Ecological Crisis: A Case Study of Central American Countries”, Economic and Political Weekly, XXXIII, (39), pp. A128-A137, 26 September.

- Siddiqui, K. (1999) “New Technology and Process of Differentiation: Two Sugarcane Cultivating Villages in UP, India”, Economic and Political Weekly, XXXIV (52), pp. A39-A53, 25 December.

- Siddiqui, K. (2014). “Contradictions in Development: Growth and Crisis in Indian Economy”, Economic and Regional Studies 7(3): 82-98.

- Siddiqui, K. (2015). “Agrarian Crisis and Transformation in India”, Journal of Economics and Political Economy, 2 (1): 3-22.

- Siddiqui, K. (2018a). “The Political Economy of India’s Economic Changes since the Last Century” Argumenta Oeconomica Cracoviensia, 19: 103-132.

- Siddiqui, K. (2018b). “Development Induced Displacement: A Critical Analysis” Turkish Economic Review, 5(2): 226-239.

- Siddiqui, K. (2021). “Agriculture, Sustainable Development, and the Government Policy in the Developing Countries”, World Financial Review, January-February, pp.44-59.

- Siddiqui, K. (2022) “Comparing the Economic Performance of East Asian and Latin American Countries: The Role of Agricultural Reforms in the Economic Transformation” World Financial Review, July-August, pp.7 – 18.

- Siddiqui, K. (2024) “Food Dumping, Rising Food Insecurity, and Hunger in the Developing Countries”. World Financial Review, June-July, pp. 8-20.

- Vasavi, A.R. (2012) Shadow Spaces: Suicides and the Predicaments of Rural India, New Delhi: Collective.

- Walker, K. L.M. (2008). “Neoliberalism on the Ground in Rural India: Predatory Growth, Agrarian Crisis, Internal Colonization, and the Intensification of Class Struggle”, Journal of Peasant Studies, 35(4): 557-620.

- World Bank (2006) India: Inclusive Growth and Service Delivery: Building on India’s Success, Washington DC: The World Bank.