The UK has been predicted by the OEDC to be the worst-performing economy of all advanced nations for 2025. Let us carefully examine the policies that led her there and consider the steps to turning things around.

I. Introduction

Recently, forecasts from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economic report portray a gloomy picture of the UK economy. According to the OECD Report (2024), the UK’s “sluggish” growth prospects have put it on course to be the worst-performing economy of all advanced nations next year. The less optimistic prediction comes as the global economy shows signs of recovery, with growth forecast to remain steady at 3% in 2024 before rising modestly to 3.2% in 2025 (OECD, 2024).

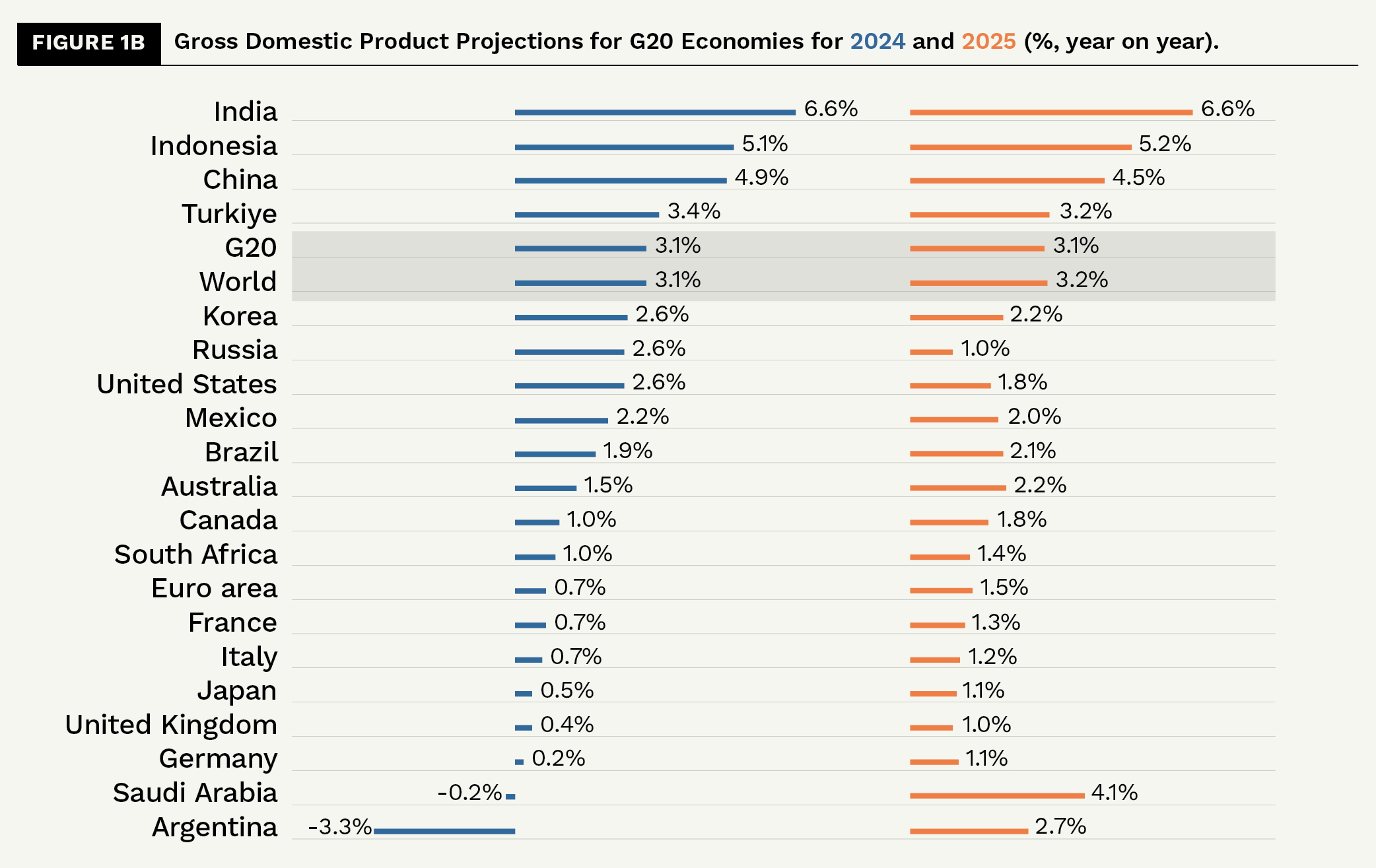

The study of the British economy is important because its performance will affect the rest of the world due to its close link with the global economy through trade and investments. The UK gross domestic product is expected to grow 0.4% in 2024, said the Paris-based think tank in early May 2024 in its latest global economic outlook. That figure is down from a previous prediction of 0.7% and less than all other G7 countries besides Germany, which is expected to be 0.2%. According to the OECD Report, inflation among its 38 member nations is expected to dip to 5% in 2024 from 6.9% in 2023, and then fall further to 3.4% in 2025. By the end of 2025, inflation is expected to return to targets of around 2% in most major economies (OECD, 2024).

The British economy is then forecast to expand by 1% in 2025, behind Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the US as the lingering effects of high interest rates and inflation continue to weigh (Siddiqui, 2024a). Among emerging economies, the OECD said there were also signs of strength. In China, where the economy has struggled in part due to a protracted downturn in the property market, growth projections were revised upward slightly from earlier forecasts.

It seems that the policy of liberalism, which the UK has been following for the last four decades, is facing a crisis in the sense that the objective it puts forward for the achievement of what it perceives as human freedom is logically impossible to achieve. There is a logical contradiction within itself that has arisen during the development of the economy to which the UK policy elites have no answer (Siddiqui, 2024b).

During the Great Depression and inter-war period, the economic crisis in the UK was resolved through government intervention. The state intervention in the economy was to correct the malfunctioning that may arise because of the spontaneous working of capitalism. This version of liberalism, in which J.M. Keynes played a major role and which he called “new liberalism”, differed from earlier versions of liberalism in so far as those earlier versions had wanted state intervention to be kept to a minimum, in the belief that the capitalist economy would reach “full employment” in the long period.

Under current globalisation, liberalism is when trade and finance are liberalised and get globalised. Because there are no nation-states, economies are open and capital is not essentially national but has been operating as global capital and a national government due to fear of triggering a capital flight, would not attempt to control foreign capital. Neoliberalism is facing crisis due to its failure to reduce unemployment, inequality, and job insecurity. In fact, the post-war Keynesian “demand management”, which was supposed to overcome the crises of overproduction and mass unemployment that plagued capitalism, requires that larger State expenditure, the panacea for the crisis, should be financed either by higher taxes on the rich or no taxes, but largely rely upon through a larger fiscal deficit. However, taxing the rich and increasing the fiscal deficit are both opposed by globalised finance capital which therefore eliminates the scope for any fiscal intervention by the state against the crisis. Then the policymakers can intervene through monetary policy, but opting for such a policy would lead to inflation that compounds the crisis (Siddiqui, 2022).

II. Falling Growth Rates

Among the advanced economies, the UK growth rates are expected to be the lowest. There was a time when a high GDP growth rate was considered necessary for alleviating unemployment and poverty in countries like ours so that no distinction was drawn, let alone any conflict perceived, between “a mere increase in production” and “a large remuneration of labour”.

Between 2019 and 2023, real GDP per head in the UK fell by 0.2 per cent. Among the G7 economies, only the growth performance of Germany (a fall of 1 per cent) and Canada (one of 1.4 per cent) was lower (See Figure 1a and 1b). In the longer term, the UK suffers from a number of challenges such as high inequality, low productivity and economic growth.

A high GDP growth, it was argued, would raise the rate of growth of employment, which would reduce the relative size of the labour reserves, create tightness in the labour market, and raise the real wage rate. Even if the real wage rate does not rise as rapidly as labour productivity in such a case, it would certainly increase faster relative to labour productivity than it would otherwise have done; at any rate, a faster growth of GDP would make workers better off, both by reducing unemployment and raising real wages compared to what they would have been otherwise.

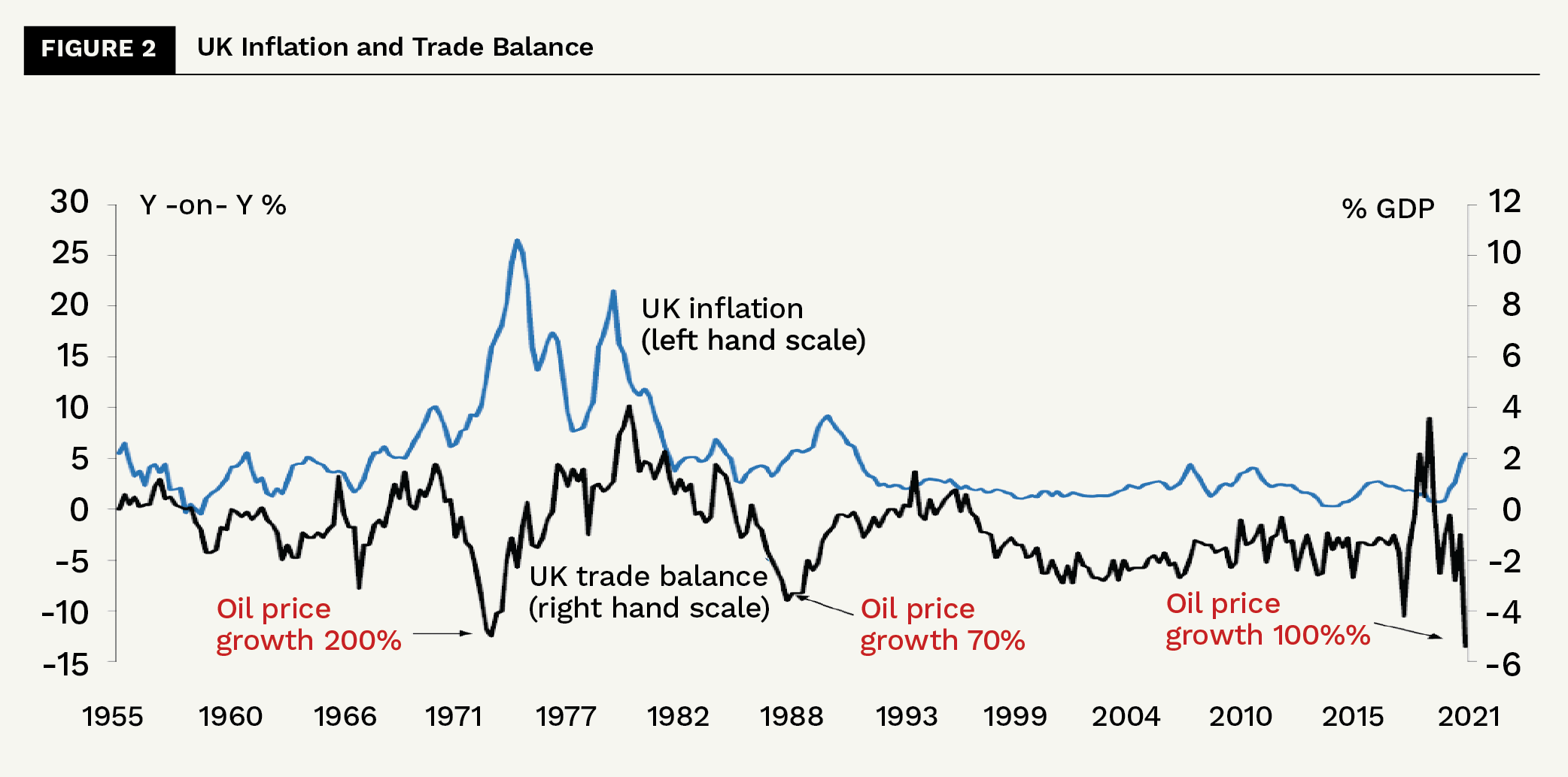

The oil price shocks in the past had led not only to inflation surges but also to large current account deficits in the UK. These have always put downward pressure on the pound. The difference this time is that the pound is allowed to adjust and isn’t the end-all of monetary policy. Although low compared to last year, inflation is still high relative to other advanced economies, and higher inflation affects exports and imports (See Figure 2).

In recent years the real gross domestic products have declined, while the current low growth rates and poor economic performance will have consequences on peoples’ living conditions. And in the long run, continued stagnation will create severe social and political challenges: higher taxes; worsening quality of public services; pervasive disappointment; and zero-sum struggles for advantage.

The pound’s depreciation is destructive when demand for the imported good is inelastic, as in the case of food and energy imports, because a larger depreciation is required to rebalance trade. The exchange rate of pound sterling is also important as it affects imports and exports. Its longer decline since 2008 reflects the economy’s relative medium-term economic performance, but it is this economic decline that should concern policymakers, not the value of the currency.

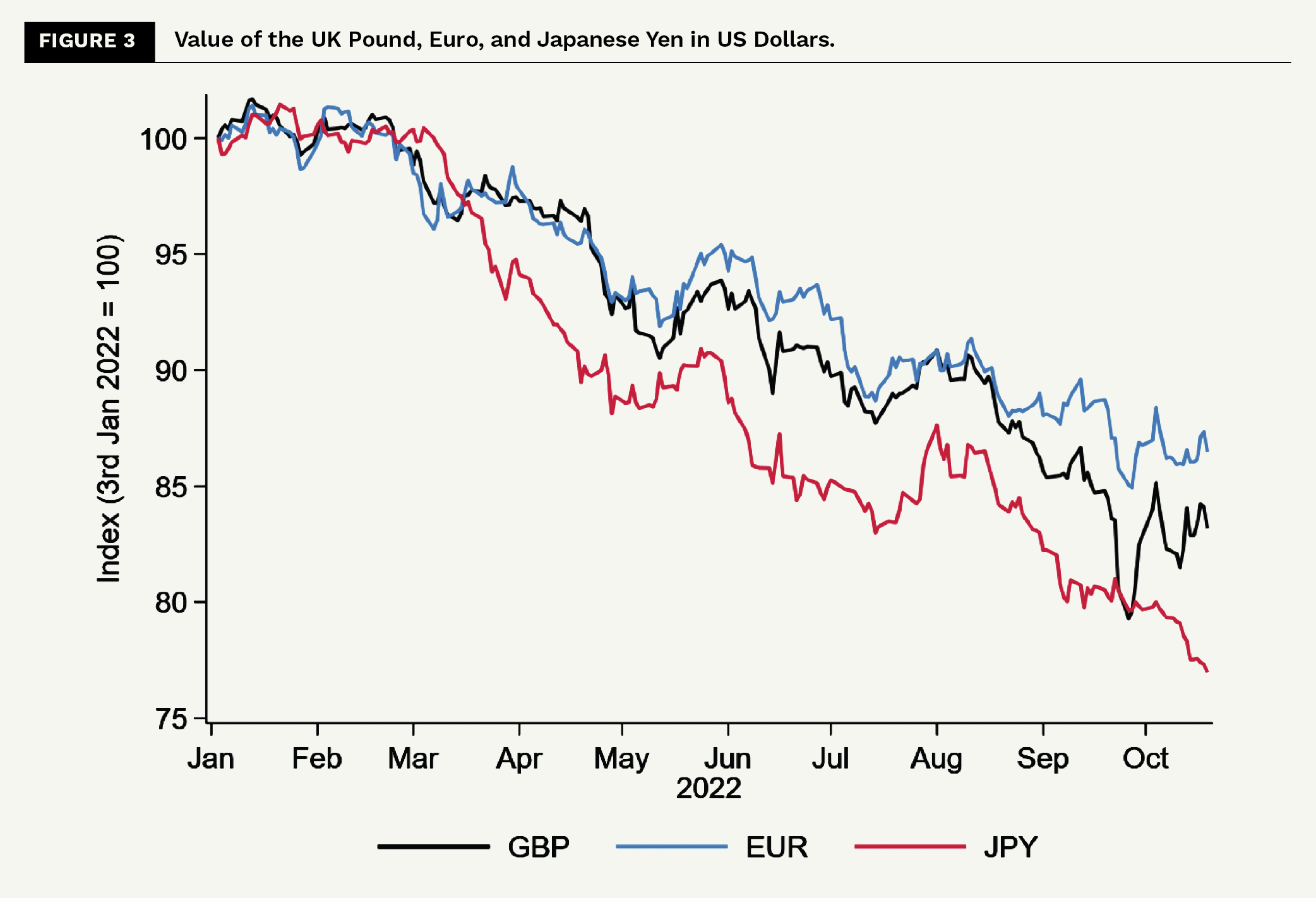

Figure 3 indicates the exchange rates of the sterling pound to the US dollar and other major currencies. This is compared with two other major currencies: the euro and the Japanese yen. The value of the pound has declined with other major currencies. It is not so much that the pound has declined, but rather that the US dollar has become stronger. The pound dropped by 4.5% in September 2022, and it recovered within an additional week, making the event insignificant compared to currency crises past. Compare this with the almost immediate and persistent 15% decline in the pound-Deutschemark exchange rate in the ERM crisis or the 30% decline in the value of the Argentine peso in January 2002 (Wolf, 2024a).

The UK does not offer a long-term fixed-rate mortgage to consumers, while such options are available in other high-income countries. With few exceptions, mortgagors in high-income countries have broad access to 10-year fixed-rate mortgages, and in most cases 30-year fixed-rate mortgages are available. Unable to insure against interest rate changes, UK households are extremely exposed to monetary policy changes, as the earlier analysis showed. The UK has one of the leading financial centres in the world, but the UK banks are unable to offer financial products that are available globally.

It seems helpful to borrowers to get the opportunity to longer-term fixed-rate mortgages. The UK yield curve is strongly inverted, which means that the annual base rate is now lower for a 30-year loan than a 5-year one. Even when including a risk premium, banks may be able to offer long-term fixed-rate mortgages at competitive rates. Further, low long-run interest rates indicate an excess demand for long-term, pound-denominated, assets.

Ethan Ilzetzki (2022) from the London School of Economics, described the current level of debt as being “high but nowhere close to where it was in the 1950s”. The rise in mortgage costs will substantially increase an already high cost of living and this crisis is to be taken seriously rather than postponing it. According to him, about a third of the UK’s households would experience difficulties in repaying mortgages due to economic crisis. Economic slowdown means housing prices are said to decline by 10 percent, and rents will likely increase. Therefore, certain policy measures need to be taken to correct it. Such measures may include balancing monetary policy and preserving credibility to meet inflation targets. The interest rate increases will increase to millions of mortgagors and indirectly to homeowners, renters, and the rest of the economy.

Fiscal policy should be pro-growth; taxing the rich and corporations and involve broadening the tax base alongside lower marginal tax rates. The government will be pressured to insure households against increased borrowing costs. This should be done in a targeted way and fully funded.

With limited fiscal and monetary space, the mortgage crisis can still be averted through debt restructuring. Banks will have to recognise that they are better off collectively absorbing small, temporary, and voluntary losses on mortgages than potentially larger, unpredictable losses through mortgage arrears, defaults, and house price declines. Government intervention is needed to mitigate problems arising because individual banks have no incentives to participate in such a scheme absent broad participation by other banks.

Unlike the US, France, Italy, and many other countries, UK banks do not offer longer-term (over five years) fixed-rate mortgages. With a steeply inverted yield curve, there is no better time to introduce these products. Government intervention may be required because long-term fixed-rate mortgages are often implicitly or explicitly guaranteed or supported by the government.

III. Crisis of Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is the mode of operation of contemporary capitalism. This system of accumulation emerged gradually in the late 1970s in response to rising prices and unemployment. Neoliberalism uses state power under the guise of ‘‘non-intervention’’ to strengthen the grip of capital by providing a greater role of the market in resource allocation, and international economic integration (Siddiqui, 2024c). Moreover, financialisation in the UK has caused lower investment in capital stock because shareholders’ power vs workers has increased. As a result, the manager’s key objectives have moved towards short-term returns and raising share prices through dividend payments. These developments of financial capitalism have negatively affected aggregate demand and growth, while redistribution of income favouring the rich who has lower propensities to consume has adversely affected the aggregate demand (Foster, 2019).

Within the ‘‘neoliberal reforms’’, privatisation of the public sector industries and services constituted an important policy element. Public sector ownership was believed to be less efficient for society, and the government should not interfere and regulate the economy. During the 1980s and 1990s, privatisation policy continued unabated, claiming that such a policy would make the UK industries more competitive and efficient. However, by the end of 1990, the UK’s gross investment rate was one of the lowest in the OECD. It seems that the privatisation drive between 1980 and 2000 had little impact on either improving efficiency or raising business investment.

The process of deregulation including the changes in capital requirements of banks and financial institutions and the creation of shadow banking has been important factors in the rise of the financialisation of the economy (Siddiqui and Armstrong, 2017a). Deregulation of the financial sector was fully supported by mainstream economists and international financial institutions. Financialisation has adversely affected investment and accumulation and diverted away from real investment in manufacturing. Financialisation also accompanied widening inequality and the introduction of austerity and cuts in welfare spending in the UK and other advanced economies (Siddiqui, 2017b). Since the 1980s with the introduction of neoliberalism and deregulation, growth has hugely relied on services and the financial sector, including the rise of credit, particularly household credit, which boosted consumer demand. Asset prices, namely housing prices, rose sharply, which gave a false feeling in the market of an increase in wealth and boosted the apparent returns on financial investments. However, there is a limit to how long consumers’ debt can be sustained and rising asset prices are unstable (Siddiqui, 2023).

For example, the privatisation of Thames Water was undertaken by then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, a radical change in economic policy as known as neoliberalism, which is facing a critical crisis. Unable to mobilise £500 million from shareholders who have benefitted the company over the years, Kemble Water, the parent company of Thames Water, defaulted on debt service payments of £190 million due in April 2024. Further, the worst conditions of infrastructure resulted from long years of underinvestment under private ownership (Chandrasekhar, 2024).

In the ideologically driven privatisation push after Thatcher’s second term as Prime Minister, she privatised in 1989, ten regional water authorities (RWAs), responsible for water supply, water quality, and sanitation throughout individual river basin areas. Till then water supply and sewerage services were considered to be one of the economic activities that were sites for “natural monopoly” because investment size and technological characteristics did not allow for competition between multiple private suppliers. The mainstream economic theory was that allowing a monopoly to be exercised by private owners would lead to profiteering at the expense of prices paid by and quality afforded to consumers.

The shortfalls in production and quality were partly a result of past government policy. Its ability to provide adequate services was undermined by a decision of the Mrs Thatcher government elected in 1979 to limit borrowing by the RWAs, which held back much-needed capital investments. As has been true of many instances of privatisation since the public sector was wilfully run down to build a case for its handover to private players.

Privatisation was not aimed at undermining monopoly, but the Water Act of 1989 protected private monopolies, giving the new private owners exclusive concessions to provide water and sanitation services for 25 years. Moreover, to attract private investors the government sweetened the sale in a number of ways. While the new private owners of the water and sewerage companies paid a total of £7.6 billion for their acquisitions, the government wrote off as much as £5 billion of debt the RWAs then owed and provided an additional cash infusion totalling £1.5 billion, known as the ‘‘green dowry’’. Private owners who paid a net of around £6 billion, began with a clean financial slate, with substantial freedom to re-price their services.

The UK’s National Audit Office estimated that in the first 15 years after privatisation, the average household bill for water and sewerage rose by 40 percent after adjusting for economy-wide inflation. The company was also lobbying for lower fines and penalties for breaches. But faced with criticism, the regulator, Ofwat, is holding back on providing more concessions. The company has accumulated £14 billion of debt servicing which eats up 28 percent of its annual revenues according to one estimate. But that did not hold back the recent payment of large dividends to its shareholders, totalling £7 billion over the 32 years from 1990 to 2022 (Chandrasekhar, 2024).

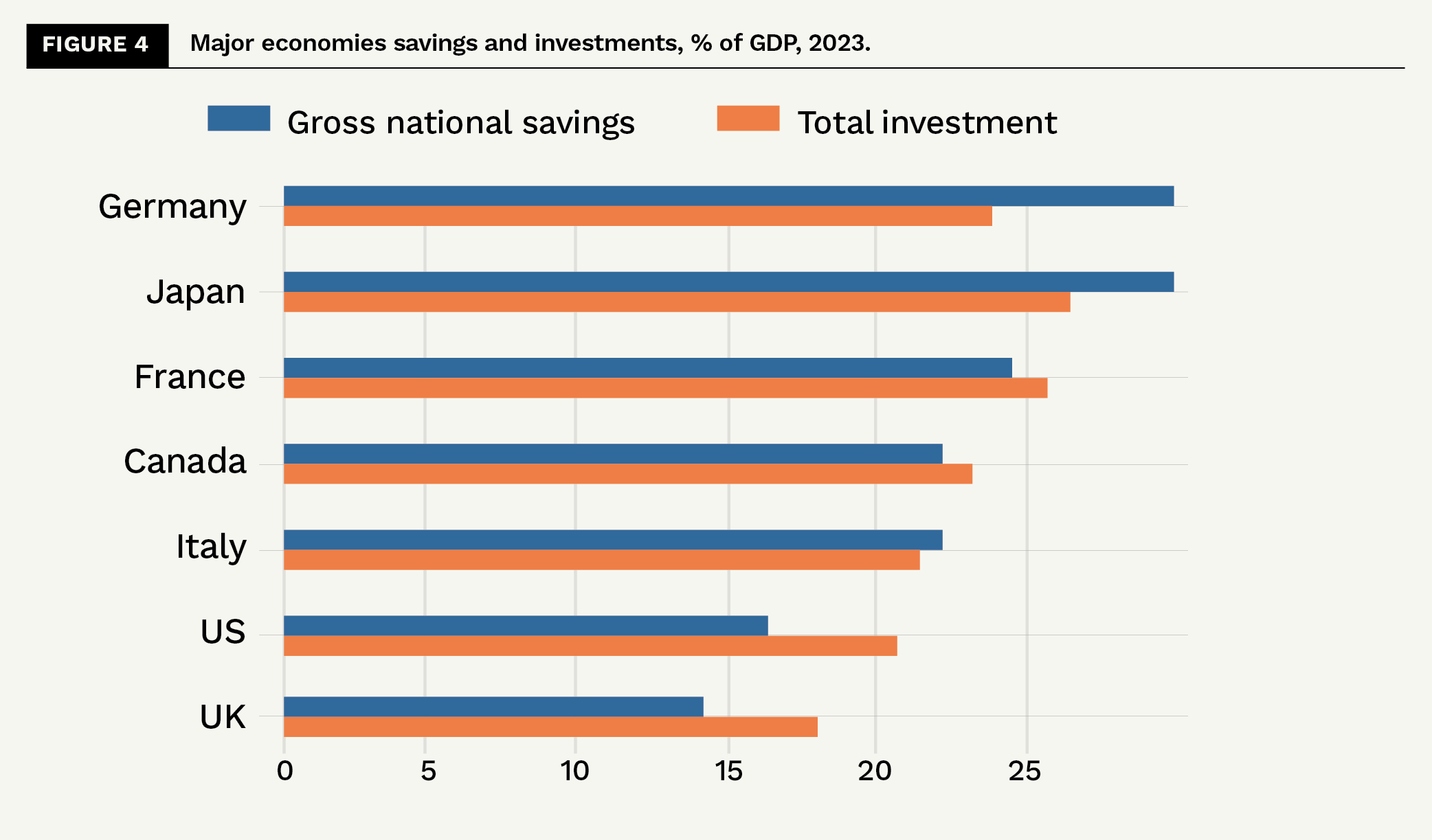

Savings and investments are very important for the growth and long-term development of the economy. However, when we look at the data, we find that the UK is the lowest among the G7 world’s major economies as shown in Figure 4. Therefore, various measures should be taken to raise private savings and pension savings above the current level of 8 percent of earnings. Again, it needs to decide which public investments will be essential if it is to achieve its goals. The government can, for example, borrow to invest in expanding the housing supply.

It is vital to examine how the financial sector has evolved and changed since the 1980s and which forces have generated the rapid expansion of the financialisation of the economy in the UK. It seems that financialisation means the increasing role financial sector, financial markets and financial institutions in the operation of both domestic and international economies (Epstein, 2005).

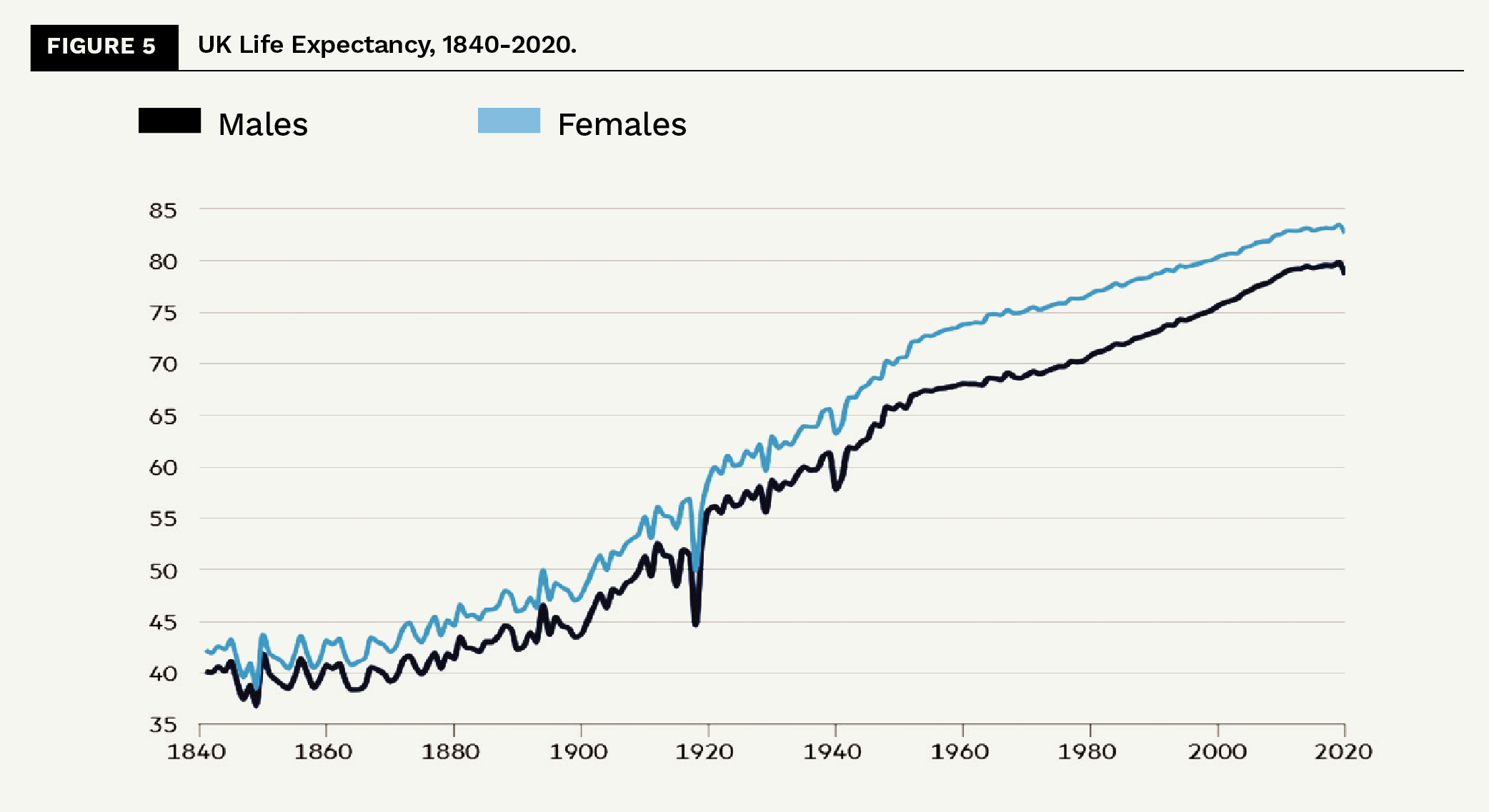

Sharp demographic changes are taking place in the UK and birth has declined, while people are healthier and living longer (as shown in Figure 5). These changes will have a huge impact on the economy and society. At present, the life expectancy has risen to nearly 80 years, of course, it differs to incomes and areas where people live. In the book, The Longevity Imperative, Andrew Scott (2024) notes that we are living longer everywhere: global life expectancy is now 77 for women and 72 for men. This new world has been created by the collapse in death rates of the young. Back in 1841, 35 percent of male children were dead before they reached 20 in the UK and 77 percent did not survive to 70. By 2020, these figures had fallen to 0.7 and 21 percent, respectively. We have largely defeated the causes of early death, by using cleaner food and water, vaccination and antibiotics. This is humanity’s greatest achievement. Yet our main reaction is to fret over the costs of an “ageing” society (Scott, 2024; Wolf, 2024b).

Life expectancy since the Industrial Revolution has doubled as shown in Figure 5 (Wolf, 2024b). Due to the rise in life expectancy, there will be a need to make several changes in people’s careers over a lifetime. Instead of one period of education, one of work and one of retirement, it will make sense for people to mix the three up. It may require people to go back to study, repeatedly. As Wolf (2024b) argues, “We will have to reorganise education, work, pensions, welfare states and health systems. People will no longer, for example, go to university or receive training only as young adults. This will be a lifetime activity. Again, mandatory or standard retirement ages will be senseless. People must be given options to work and not to do so at various stages of their lives. Just raising retirement ages all round is both inefficient and inequitable since life expectancy is so unevenly distributed.”

IV. Rise of Financialisation

In recent decades, the financial sector has grown disproportionately within the process of production and accumulation, and it has penetrated less traditional areas. For instance, in the social areas, financialisation encourages short-term investments and is opposed to economic reproduction and meaning beyond mortgages but into consumers’ credit. This is an expansion of creditors simply, or does it involve a requirement for surplus production and appropriation beyond expected normal commercial activity?

For example, between 1980 and 2015, the manufacturing output fell by 0.4%, and employment fell by 2.6% annually. The growth of UK manufacturing output between 1973 and 2010 was much lower than in other developed countries (Siddiqui, 2020). All these economies had witnessed a fall in manufacturing employment and revenue since the 1980s. However, the decline of manufacturing was much sharper in the UK than in other developed economies. As a result, manufacturing declined and had 17% of the UK gross value added in 1997, compared to 26% in Germany for the same period. And such policy contributed to the long-term slowdown of industries in the UK.

The expansion of finance is the key element of neoliberalism. As Saad-Filho (2011: 243) notes, “Financialization and the restructuring of production are underpinned by the transnationalization of circuits of accumulation, which is commonly described as ‘globalization’. These developments have recomposed the previous ‘national’ systems of provision at a higher level of productivity at the firm level, created new global production chains, reshaped the country-level integration of the world economy, and facilitated the introduction of new technologies and labour processes while compressing real wages.” Financialisation has supported a significant rise in the rate of exploitation foremost seen in a corresponding decline in the wage share of national income in most countries (Foster, 2019).

The current recession and stagnation in the UK are related to increased financialisation of the economy in recent decades. The financial crisis of 2008 and soon after the recession of 2009 and then the Eurozone crisis starting in 2010. Financialisation or finance-dominated capitalism means the deregulation of the financial sector and the rise of shadow banking and the rise in private sector debts and rise of shareholder’s power and finally the dominance of the financial sector in the overall economy. With regards to distribution, it means a rise in the share of capital including profits, interest payments and dividends, while a decrease in the share of workers (Siddiqui, 2023).

V. Conclusion

The ‘‘golden period of capitalism’’ i.e., 1950-1973, which was replaced by neoliberalism and pro-market policies in the 1980s both in advance and soon after this policy, was also adopted in the developing economies. However, the neoliberalism period experienced several financial crises, such as Mexico (1994), Turkey (1994), East Asia (1997), Russia (1998), Argentina (2001) and global financial crisis (2008). Epstein (2005) explains the rise of financialisation in the last four decades as ‘‘the expansion and proliferation of financial investments, including financial derivatives and securitisation’’ and the latter is defined as ‘‘the creation and instance of debt securities and bonds, where the interest on bonds and the repayment of the principal comes from the cash flows generated by a separate pool of assets’’.

Margret Thatcher adopted a neoliberal policy with the increased role of market forces in economic policy. Such policy was continued by the subsequent Labour and Conservative governments since then. Thatcher’s economic and social policy aimed at re-establishing the supremacy of the “free market” policies, also known as neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism is widely seen as a political, ideological policy of capitalism into a new development phase. As Foster (2019) notes, neoliberalism is “an integrated ruling-class political-ideological project associated with the rise of monopoly-finance capital, the principal strategic aim of which is to embed the state in capitalist market relations. Hence, the state’s traditional role in safeguarding social reproduction – if largely on capitalist-class terms – is now reduced solely to one of promoting capitalist reproduction. The goal is nothing less than the creation of absolute capitalism.”

Deregulating previously regulated sectors such as power, transportation and communication led to a drastic reduction in trade union memberships and wages. Privatisation of public services has often led to low wage rates under private companies. Reducing trade union memberships and giving up fiscal policy as a tool to keep unemployment low, both these factors have reduced the bargaining power of the workers in the UK.

Since 1980, corporations’ borrowing has risen sharply, but this has not transpired into productive investments. Instead, the big corporations have invested this money into speculation and real estate. Big corporations have been reluctant to invest in manufacturing, resulting in low productivity growth. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, this pattern has been seen in the UK. For example, the UK’s productivity growth between 2010 and 2019 was 2%, the lowest recorded since the last 19th century (Siddiqui, 2020). The neoliberal economic policy which the UK pursued since 1979, mobility of capital, keeping real wages low and increasing the rate of surplus value and so on, has proved to be incapable of sufficiently raising the profit rate and rate of productive accumulation and even cuts on taxes on rich and corporations have not helped much.

Mainstream economists assume that the private sector is more productive than the public sector, and their explanation is based on the supply side and does not consider demand-side conditions. They also emphasise the importance of competition and market forces to improve efficiency. They argue that deindustrialisation and relatively poor productivity growth were due to too powerful trade unions, red tape and government regulation.

Financialisation has generated wealth-based and debt-financed consumption in advanced capitalism like the US and the UK, hence creating the potential to compensate for the depressing demand effects of financialisation. High growth of consumers’ domestic demand was financed by household debts, leading to a rise in debts. For example, between 2000 and 2008, private consumption contributed up to GDP growth of nearly 80% in the UK and US and more than 55% in Spain (Hein, 2019).

The 2008 global financial crisis was soon followed by an economic recession. Not only the financial losses should be socialised, but also big banks should be taken over under public control. There seems to be an increased need to rebalance the economy as well as a radical policy change to give a greater role to the manufacturing sector. The UK still has certain areas in competitive manufacturing like aerospace and pharmaceuticals and needs to increase investment, which would lead to increased output and employment in the manufacturing sector.

There are several economic challenges facing the UK economy and the government must take urgent economic reforms such as the country needs a strategic long-term vision. This means that the government should build a rolling five-to-ten-year vision of how the world and national economies might evolve. More government intervention is needed to invest in environment-friendly technologies and skills and encourage innovation to deal with the challenges: demographic change and ageing, climate change (Siddiqui, 2024d). Rising inequality in recent decades must be addressed urgently, and wages should be increased to expand aggregate demands and purchasing power among low-income households.

About the Author

Dr Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

Dr Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

References

1. Chandrasekhar, P. (2024). The Collapse of Neoliberal Privatisation, 19th April. https://www.networkideas.org/news-analysis/2024/04/the-collapse-of-neoliberal-privatisation/

2. Epstein, G. (Ed.) (2005). Introduction: Financialisation and the World Economy (London: Elgar & Cheltenham).

3.Foster, J.B. (2019). “Absolute Capitalism”, Monthly Review, May, New York. https://monthlyreview.org/2019/05/01/absolute-capitalism/

4. Hein, E. (2019). “Financialisation and Tendencies Towards Stagnation: The Role of Macroeconomic Regime Changes and After the Financial and Economic Crisis 2007-09”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 43: 975-999.

5. Ilzetzki, E. (2022). UK Financial Crisis of 2022: Retrospective Diagnosis and Policy Recommendations, London School of Economics. https://www.lse.ac.uk/CFM/assets/pdf/CFM-Discussion-Papers-2024/CFMDP2024-08-Paper.pdf

6. OECD. Economic Outlook (2024). Preliminary Report May, OECD: Paris. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/69a0c310en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/69a0c310-en.

7. Saad-Filho, A. (2011) “Crisis in Neoliberalism or Crisis of Neoliberalism?” Socialist Register, Vol.47, pp.242-259.

8. Scott, A. (2024). The Longevity Imperative: Building a Better Society for Healthier, Longer Lives, Basic Books: London.

9. Siddiqui, K. (2024a). Deepening Economic Crisis in the Advanced Capitalism. The World Financial Review, April-May, p. 28-38.

10. Siddiqui, K. (2024b). Neoliberalism and the Performance of the UK’s Economy: A Critical Review. World Review of Political Economy, Forthcoming.

11. Siddiqui, K. (2024c). Climate Change, Capitalism, and Invisible Hands of the Market: A Critical Review. The World Financial Review, April-May, p. 70-78.

12. Siddiqui, K. (2024d). Revisiting the Japan’s Economic Stagnation. The World Financial Review, February-March. ISSN:1756-3763

13. Siddiqui, K. (2023). Marxian Analysis of Capitalism and Crises. International Critical Thought, 13(4), p. 525-545.

14. Siddiqui, K. (2022). Problems of Inflation, War in Ukraine, and the Risk of Stagflation. The European Financial Review, April/May, p. 5 – 14.

15. Siddiqui, K. and Armstrong, P. (2017). Capital Control Reconsidered: Financialization and Economic Policy”. International Review of Applied Economics 32(6):1-19, March.

16. Siddiqui, K. (2020). A Perspective on Productivity Growth and Challenges for the UK Economy. Journal of Economic Policy Research, 7(1), p. 1-22.

17. Siddiqui, K. (2017a). Capital Liberalization and Economic Instability. Journal of Economics and Political Economy, 4(1), March, p. 659 – 677.

18. Siddiqui, K. (2017b). Austerity as a Tool of Fiscal Consolidation: Theoretical and Empirical Perspective (Edi) S. Owsiak, Public Finance, and the New Economic Governance in the European Union, p. 116 – 166, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

19. Wolf, M. (2024a). The UK needs a reform road map to avoid stagnation. Financial Times, April 15, London. https://www.ft.com/content/9b3eab24-564a-48ec-ac2a-777b115a0372.

20. Wolf, M. (2024b). Increased Longevity Will Bring Profound Social Change. Financial Times, May 13, London. https://www.ft.com/content/a8f33209-3507-4364-98be-61b3bb464fbb.