Is the WTO´s global food liberalisation policy more harmful than good? How has relying on international trade for food supply led to food dumping? Dr Kalim Siddiqui makes a deep dive into how global policies shape the economy of developing nations and the very lives of farmers.

I. Introduction

The study analyses the issues of food dumping and food insecurity in developing countries. I also examine the relationship between the World Trade Organisation (WTO) policy of global trade liberalisation on food security and food self-sufficiency in poor countries. Specifically, it investigates whether this policy undermines food security in poor countries by examining its impacts on food importation and food dumping. The available statistics indicate an increased food import dependency on international trade in many poor countries. Food importation not only exposes producers and consumers to increased vulnerability both to worsening terms of trade and to fluctuations in commodity prices but also exposes the domestic food-producing industries to the danger of extinction through steep competition.

Food dumping and food insecurity are very important to examine as it has long-term economic and social impacts on both agricultural exporting and importing countries. It undermines the economic viability of the farmers in developing countries who aim to sell in the domestic markets or intend to sell overseas. Such practice distorts competition in local markets due to huge income and asset differences between farmers in poor and rich countries. Food dumping has become a very important policy tension between the rich and poor countries at WTO trade negotiations. We must not ignore that global trade in agricultural commodities is controlled by four big agricultural corporations that control more than 80 percent of cereals sold in international markets.

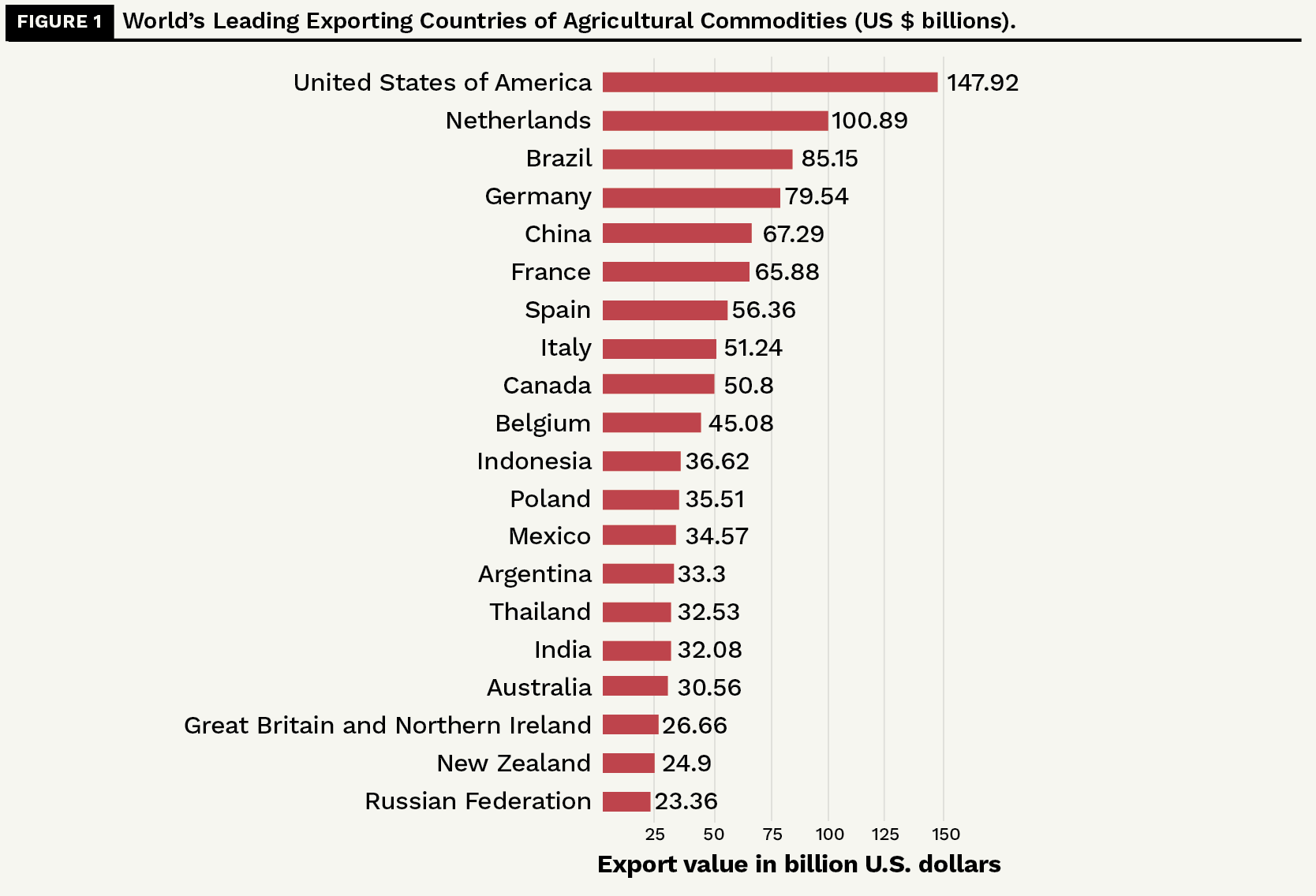

Farmers in the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) are big in terms of acreage of operation of farms, capital assets they possess, and use of chemical inputs. They are the world’s largest exporter of agricultural commodities. The four largest exporter corporations such as Cargill, ADM, Bunge, and Louis Dreyfus, based in rich countries, dominate the international commodities markets. Despite some new countries joining the exports of agricultural commodities, still, in international markets, a large proportion of exports are dominated by six to seven countries.

Moreover, the world population has increased during the last few decades and people are living longer. People also have diversified their diet and eating rice and grain, while consuming more meat, vegetables, and processed food. Since 1995, with the establishment of WTO and trade negotiations, world trade has risen sharply, including agricultural commodities.

II. What is Food Dumping?

Food dumping means exports of food commodities at prices below the local cost of production thus forcing the local farmers to leave farming as an unviable activity. Such policy hurts farmers in importing countries, especially poor countries with little power to defend their markets and agrarian communities. In the name of competition and efficiency, trade liberalisation in agriculture commodities was imposed through Uruguay Rounds in the 1990s by the WTO with full support from the US and EU, who had huge agricultural surpluses and therefore, were seeking new markets to sell their surpluses. It is unfair competition between the large farmers of the Global North and the poor and small farmers of the Global South. The rich countries encourage the over-production of a few agricultural commodities, which is an important source of food dumping in a never-ending battle to increase yields.

It is estimated that farm incomes have declined by 50 percent since 2013 and the US farmers rely on off-farm income and government production and income support to stay as farmers. The policy of maximising short-term profits ignores long-term viability and sustainability. Such policy had long-term severe negative impacts on the environment such as impact on soil, ecology, and biodiversity. This is because markets externalise environmental costs.

Poor countries mainly rely on imports of agricultural commodities, which undermines self-sufficiency in food, and adversely impacts rural communities and reduces rural employment and incomes. For example, imports of rice in Haiti in 2010 were encouraged by the IMF, World Bank, and neoliberal economists to promote free trade in agricultural commodities (World Bank, 2018), by overlooking dumping issues. This raised the balance of payment crisis making Haiti more dependent on food imports, as global market prices changed sharply, the country became more vulnerable. Liberia in 2007 opened their markets for food imports due to pressure from the IMF. Soon, international food prices rose, and the government was unable to pay higher prices of imported wheat, and the food insecurity increased.

Food imports, in the short run, help poor countries facing food deficits to reduce food prices and increase food availability as well as help urban consumers to buy cheap food. In the long run, however, such policy undermines the agricultural sector, self-reliance, and food independence, thereby reducing long-term investments in the rural sector, including the farming sector.

The US is the world’s largest producer and exporter of agricultural commodities (See Figure 1). The US-based agribusiness dominates the global food market. However, for several agricultural commodities in which the US is the leading exporter to the world’s market, the prices it charges in the global market are lower than the cost of production. For example, in 2015, the US exported wheat at 32 percent lower than the cost of production, other commodities like soybeans at 10 percent, corn at 12 percent, and rice at 2 percent (Murphy and Hansen-Kuhn, 2017).

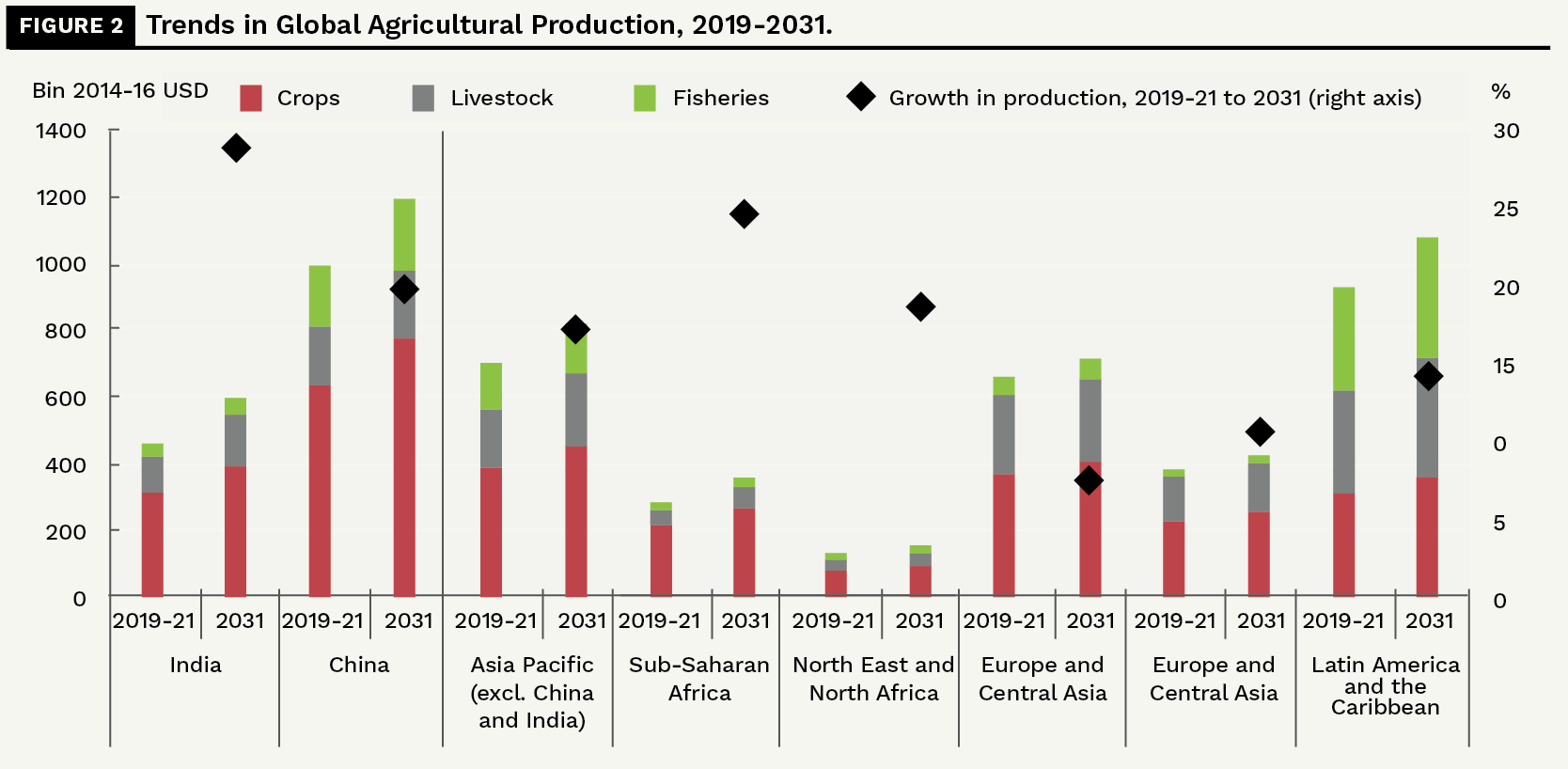

Worldwide in the coming decade, global agricultural production (measured in constant prices) is projected to increase by 17 percent (See Figure 2). However, the growth will be predominantly located in large-population countries such as India, China, and Indonesia (Siddiqui, 2015). It will be driven by productivity-increasing investments in agricultural infrastructure and research and development; the mobilisation of production resources will rely on the use of more water and new inputs i.e., more intense use of agricultural inputs.

Dumping undermines the farmers in developing countries to compete in the global markets. For instance, in early 2000, the US dumping of cotton was complained to WTO by Brazil and also by many African countries. The WTO ruling favoured Brazil and pointed out that government subsidies provided US farmers an unfair advantage and suppressed the world market price, which adversely affected Brazilian farmers. In 2009, the US agreed to pay Brazilian farmers compensation.

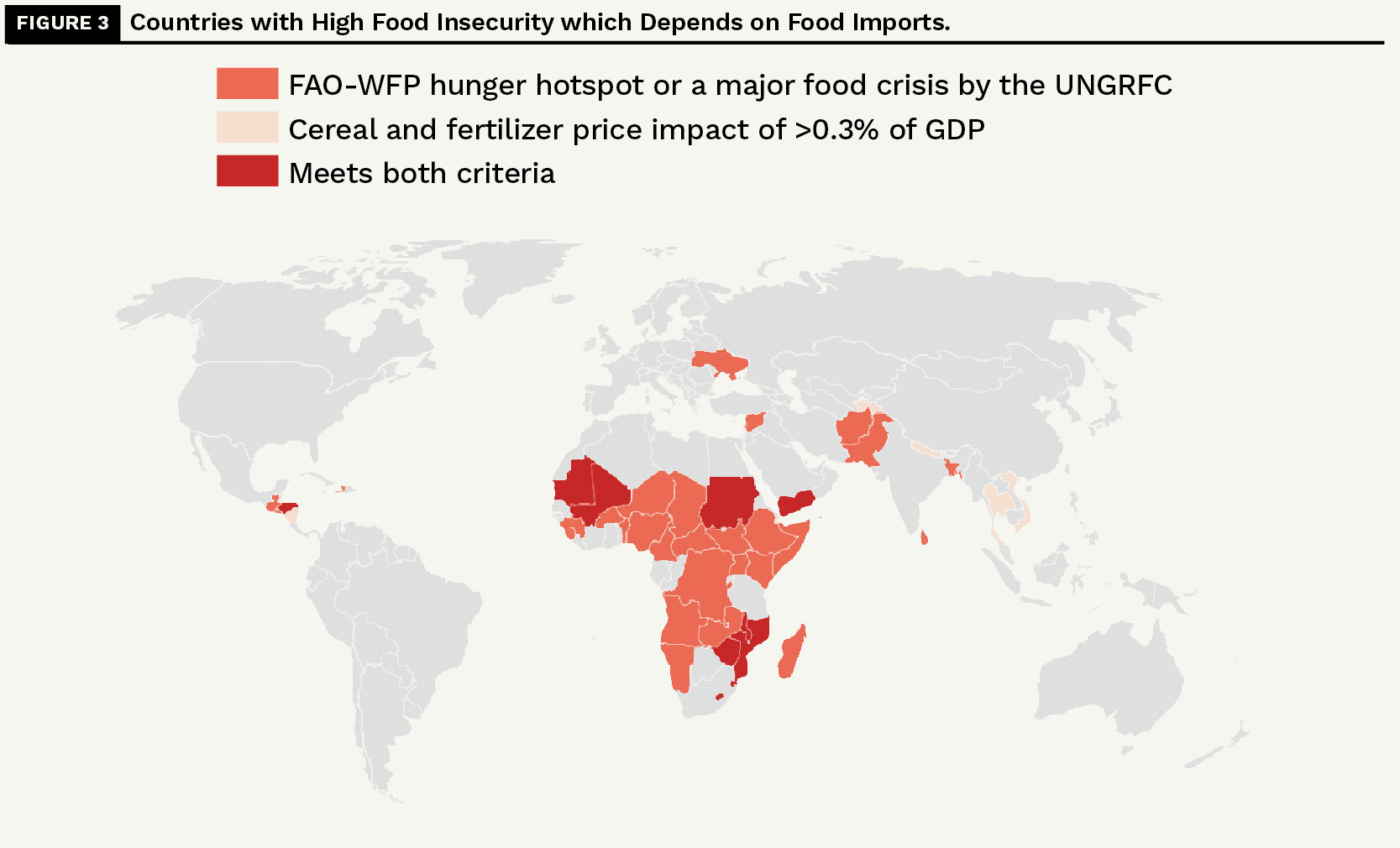

The debt crisis leading to the adoption of IMF’s ’’Structural Adjustment Programme’’ imposed in the 1980-1990 liberalised trade and global food corporations got greater access to world food markets. For instance, in West Africa, there is no doubt that the food trade rose, but the availability of food and food consumption fell below levels in the 1960s. The situation slowly improved between 2000 and 2015, but since 2016 food consumption in West Africa fell, and 27 percent of the population are living with severe food insecurity (See Figure 3) due to rises in inequality and income disparity. This is affecting more than 330 million people with 240 million being malnourished, particularly in rural households.

A five-fold increase in population since independence has exacerbated the problem, leaving African people four times more affected than any other region and with food insecurity increasing. This situation has arisen despite many African countries’ exports of agricultural commodities. The focus on large farms and Western technology in agricultural policies for national food sovereignty has meant that rural economic development has been neglected, recognising the influence of global political and market forces on food prices, and food consumption.

Historically, colonialism fundamentally had disrupted and suppressed food security systems, which resulted in widespread poverty, chronic food shortages, and malnourishment. Such policy had undermined local knowledge, biodiversity, and self-reliance in food production. Post-independence, there were limited resources to meet and resolve enormous challenges of backwardness, mass poverty, illiteracy, and hunger. African countries did not achieve the political, cultural, and economic changes that were necessary to ensure their governments’ independent economic development to help the social and economic needs of the inhabitants (Mamdani, 1996).

By focusing political and economic development on resource extraction and neglecting the biophysical limitations, environmental degradation and social inequality increased, and unpredictable rainfall events now led to human catastrophes. Soon after independence, the Global North made a conscious decision that the free countries should pay the cost of addressing the colonial underdevelopment, repay the loans for the failed developments of the 1950s-1970s, continue to accommodate the needs of the Global North, and pay compensation to re-possess alienated land. This curtailed the new nations’ ability to invest in rural economic development. Moreover, the post-independence governments continued the expansion of non-value-added exports to the Global North. Investment in African institutions and policies, to foster growth and equitable employment in domestic and regional economies, was neglected. International institutions dominated in formulations of policies, which served the political and economic interests of the Global North.

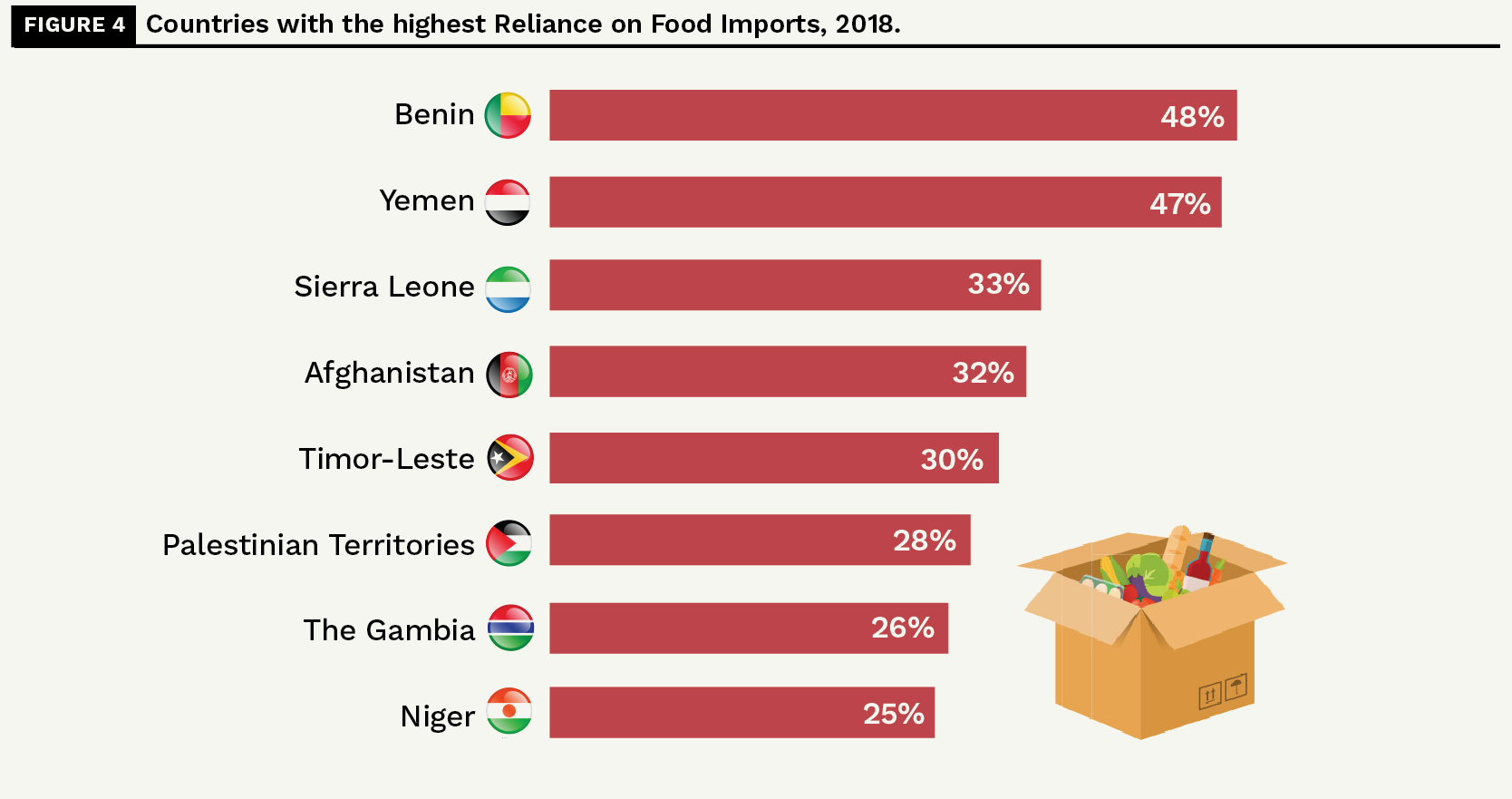

Trade liberalisation made protection of domestic farmers nearly impossible, while such policy made self-sufficiency in food production unviable which destroyed livelihoods and created food import dependency for countries with the highest reliance on food imports (See Figure 4) and only served the interests of big global corporations. International trade regimes did not incorporate fair-trade agreements for the Global South. Hence, the global corporations with their huge finances and lobbying undermined African food security, resulting in financial dependency, and increasing the balance of payment crisis (Koning, 2017).

The international financial institutions provided capital to carry out their macroeconomic growth agenda, with the expansion of infrastructure, motorways, and foreign investment and increased reliance on the greater role of big corporations in the production, marketing, and distribution of products. Their key recommendation policy includes an increase of non-food exports and productivity by using new technologies, integrating the agricultural sector with global agro-business corporations, and thus expanding rural employment.

However, the benefits of the open trade in food commodities tend to accrue to the largest producers and to the agribusinesses that dominate the global food supply, these big corporations profit when prices rise, while the farmers face the risk of unpredictable weather, climate change, or unstable markets. If the world prices of agricultural commodities fall, then limiting production is not the best option, as no individual farmer can affect the market, meaning the farmer must increase output and hope that more output can compensate for lower prices.

III. The IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organization (WTO)

The macroeconomic crisis was followed by a debt crisis in the 1980s-90s in most of the developing countries. During this period, their economy was adversely affected by the global recession that followed the oil crisis, falling commodity prices, and mounting foreign debts, which resulted in escalating current account deficits and worsening terms of trade. Under such circumstances, the crisis in the developing countries could have been avoided if they could cut down luxury imports, and fund large projects while strengthening domestic economies and production, and the international financial institutions should have supported the creation of better export commodity prices and fair trade.

The World Bank and other international banks provided capital to mega projects without critically examining their feasibility and viability (World Bank, 2018). Many developing countries had difficulties repaying these loans due to the appreciation of the US dollar – which led to rising US interest rates as these overseas debts were to be repaid in US dollars – and corruption. With declining commodity prices in the 1980s, debt repayment became an impossible task which rose to more than four times its original debt. To bail out the economies in poor countries in the 1980s-90s was subject to the acceptance of the IMF’s Structural Adjustment Policies. That includes allowing big international corporations to buy the country’s resources, and the sharp reduction in spending on health, education, agriculture, and subsidies to farmers. While in the name of earning foreign exchange, foreign capital was encouraged to invest in the cultivation of crops for exports by clearing land or converting agricultural land to the production of biofuel, animal feed, and carbon off-sets. As a result, foreign companies’ demand to buy lands surged in most African countries and this contributed to the neglect and decline of food production leading to domestic food shortages, rising food prices, and loss of livelihoods in most African countries.

The focus on export crop production, with full support from international financial institutions and local elites, meant that funds were unavailable to address the research and development needed to develop local food security, including a production system suitable for the diverse biophysical and socioeconomic conditions in Africa, to increase productivity in nutrient-poor soils and to increase investment in livestock to improve household income and soil fertility.

After the Second World War, the process of decolonisation began, and the question arose of how to remove backwardness and mass poverty in the colonies. This was also the period when the IMF, World Bank, and United Nations were created and the task of these critical international institutions was to address the economic disparity created by centuries of exploitation and colonialism, but they were vehemently opposed by the US, Britain, and France. They also opposed the formation of the World Food Board, to provide global supply management to avoid price fluctuations caused by scarcity and gluts of essential foods. The formation of international trade organisations favouring the poor farmers of the Global South could have helped to pursue fair trade and reduce the few powerful companies controlling trade in food commodities and this could have helped in the pursuit of food sovereignty, food security, and reduced food price fluctuations and the market manipulations by a handful of big corporations (Koning, 2017).

The colonial system was based on the export of agricultural commodities and minerals often with inappropriate production systems, which were to serve the interests of foreign companies, rather than promoting local rural economy and food security. This policy continued in the post-colonial period as well. This resulted in severe local food shortages and a movement away from traditional mixed production systems. The politically independent governments did very little to economically move away from past colonial relationships. These governments always saw Western agricultural production systems and technologies as the best to solve the food crisis. This included the production of rice, wheat, and maize, which were not staple crops in most African countries. They opted for this high-input high-output production, which resulted in a deep agrarian, environmental, and balance of payment crisis. The large farms and imported new inputs, besides increasing the imports and debts, had failed, particularly in countries with a predominance of small farms and huge unemployment. Without the enabling state-driven market institutions that accompanied the Green Revolution in South Asia (Siddiqui, 1991), these production systems have not led to increased productivity and growth in the domestic agricultural sector in African countries.

In response to the debt crisis, the trade liberalisation policies forced poor countries to cut spending on agriculture, education, housing, and health and allowed private foreign investment to extract the resources that were vital for local communities’ livelihoods. A vicious circle of debt and interest payments drained Africa and little money was left for local agriculture development. This kept Africa in poverty and remains a barrier to rural development and locally suitable domestic food production.

The increasing price of imported food since 2000 has encouraged local farmers and developers to invest in farming. As a result, the number of farms of 5-20 hectares has increased in many African countries. This has been driven by new players with money often earned from non-farm activities. This presents an opportunity for improving productivity and viability. However, there is also the potential for displacement and loss of livelihoods for local communities through deforestation, environmental impacts, and transfer of farmland from domestic food production to export crop production. More recently, the region has become vulnerable to international and domestic supply chain disruption as was witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Soon after independence, the dirigisme regime in India prevented land encroachment by the Indian capitalists and foreign agro businesses into agriculture (Siddiqui, 2014; also see 2018a). The government also protected agriculture from the vicissitudes of global market price fluctuations and provided subsidies on farm inputs, invested in irrigation, and guaranteed remunerative prices through government procurement of some food commodities (Kohli, 2004). However, under neoliberalism, insulation of the agricultural sector has ended and it seems that not just capitalism within agriculture is developing, but also being superimposed by the domestic and foreign capital upon farmers in India. The increased role of the market led to a drastic squeeze in the profitability of farmers, along with the cost of living rising due to the privatisation of health and education. The effect of this increased marketisation and withdrawal of government support resulted in severe hardship and suicide of over 300,000 farmers in the last three decades in India.

For example, at present for India, the agriculture sector plays an important role in the Indian economy and its better performance is crucial for inclusive growth. This sector at present contributes only 17 percent of the GDP, while it employs 60 percent of the total employment. Moreover, the forward and backward linkage effects of agriculture growth will have positive effects on other sectors as well. The major challenge for the Indian economy is that the share of agriculture in GDP decreased from more than 60 percent in 1950 to 25 percent in 2000, 20 percent in 2005 and further to 16 percent in 2022. However, two-thirds of the total labour force still relies on the agriculture sector for employment (Siddiqui, 2018b).

India joined WTO in 1995 and the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) was signed with the WTO, which prevents the country from providing export subsidies to agricultural commodities, this also puts constraints on the use of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) which provides subsidised food to poor households. The procurement system supports farmers who sustain the agriculture sector. India’s minimum price support is being challenged by the WTO that India has breached the rule specified by the AoA agreement. As a result, the Indian government is gradually withdrawing subsidies provided to farmers, which have been very important to protect farmers’ incomes. Moreover, the public stockholdings of food grains to safeguard the low-income groups are under attack.

IV. The persistence of food insecurity

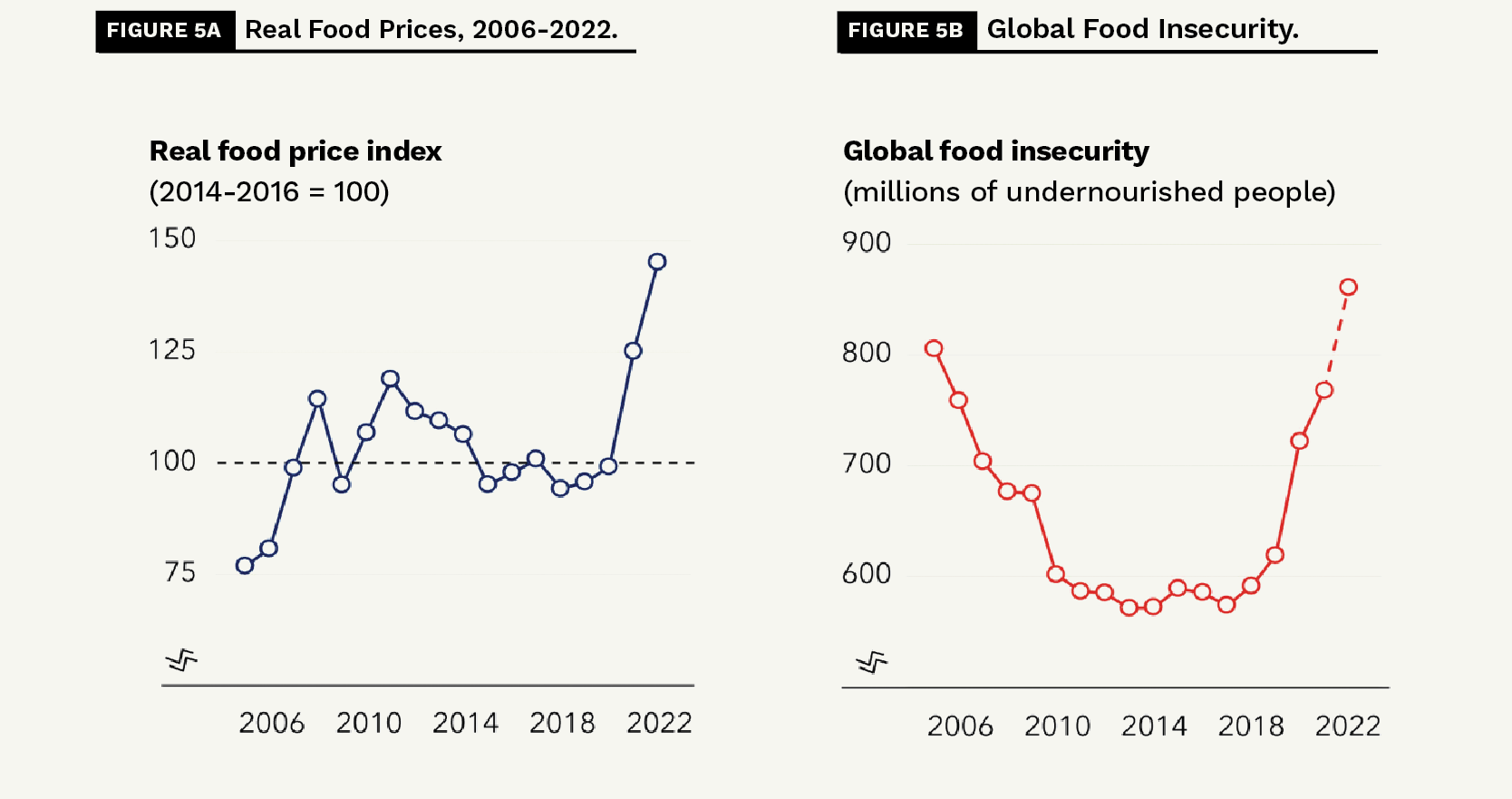

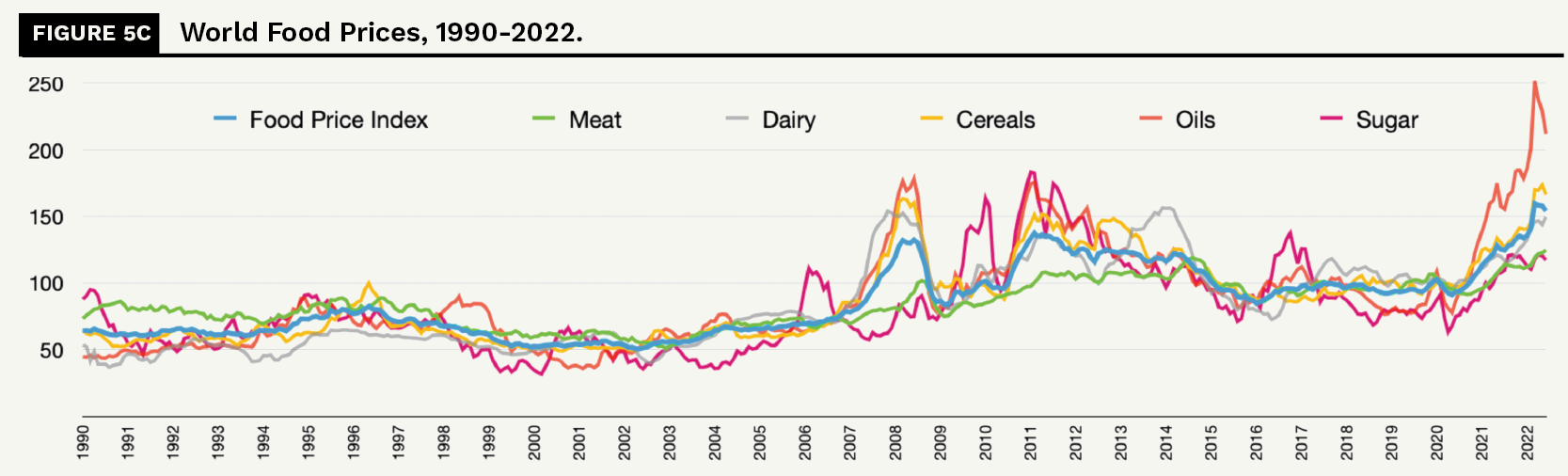

Africa is the only region in the world that increased export production in the 1980s and 1990s, but it also coincided with a decline in per capita food production and a rise in food insecurity in poor countries. Even though most African countries were net exporters of agricultural products, cereal imports grew from 2.5 to more than 15 million tons between 1960 and 2000, and by 2010 Africa’s average per capita income was less than half that of other developing countries. Poverty remains the main barrier to accessing food. In rural areas in particular, millions of people are at the mercy of a market-driven distribution system, foreign aid, commodity speculators, and unstable food prices (See Figure 5 a, b, c).

COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war had a very severe impact on the food shock, which fell sharply. The suffering is worst in 48 developing countries, many highly dependent on imports from Ukraine and Russia – mostly low-income countries. Of those, about half are especially vulnerable due to severe economic challenges, weak institutions, and fragility.

Many African governments used foreign borrowings to subsidise chemical fertiliser, credit, and water for large farms. These farms were allocated to the elites who received a large share of governments’ agricultural development funds in the 1970s for example, 50 and 80 percent in Nigeria and Ghana, respectively. Similarly, the large farmers in Ghana received cheap land for rice production in the 1970s. The cultivation of rice requires huge water inputs. But the land allocated for rice farming had 20 percent of arable land in 1975, they also received 75 percent of imported chemical fertilisers, most of the improved seeds, new machines including tractors at subsidised prices, and huge amounts of cheap credits (Siddiqui, 1997). These subsidies to large farmers did little to improve food production or create employment but rather encouraged corruption and nepotism. Mechanisation was also economically unviable when commodity prices were low. Finally, the efforts to boost the large farms and increase food output in Ghana and Nigeria miserably failed and proved to be very costly, biased against the small farmers, and failed to reduce food imports.

The African governments failed to invest in agriculture towards self-sufficiency in food production, especially food for local consumption, and to facilitate the integration of food production into regional economies. Moreover, foreign investors were biased towards foreign technologies and inputs, thus, creating barriers to integrating agriculture into the domestic economy and generating economic growth and employment.

Africa, for example, is dominated by small farms, cultivating less than 5 hectares of land, but accounting for over 80 percent of farms and around 90 percent of agricultural output. Despite this, small farms were not included in the government’s plans for agriculture development and food security. The small family farms remained under-resourced, and government policy undermined their viability. The local governments failed to increase food production with the help of small farms and local resources. If they had supported small family farms, they could have strengthened domestic food security and the national economy (Koning, 2017).

To understand food sovereignty and food security, we must examine production and consumption relations in contemporary agriculture because the core of food sovereignty is to take into consideration the socio-economic power in the market. As Akram-Lodhi notes: “The prevailing set of social-property relations within which food providers and food consumers are embedded in capitalism – the means of production are under the control of a socially dominant class, labour is free from significant shares of the means of production and free to sell its capacity to work, and the purpose of commodity production is seeking of profit. The localised smallholder farming model that is central to food sovereignty’s alternative food system, … as an ’incubator’ of food sovereignty cannot be abstracted from capitalist social relations, which are defined by relations of exploitation between capital and classes of labour. Smallholder farming is currently subordinated through a range of mechanisms under the corporate food regime, to capitalist social property relations.” (Akram-Lodhi, 2015: 566)

To Achieve food security in the developing countries would require more reliance on local farmers to be integrated into income-generating activities such as rural industries, promotion of livestock, fisheries, and so on, so they can pay for services they need. Not all small-scale farmers can become viable, and land consolidation is needed for farmers with the productive capacity to expand and specialise. Relying on large farms means displacement of farmers, even if some small farms are unviable, they will be reluctant to sell as there are no alternative employment options for them. Forcing them to leave villages would generate a huge wave of rural-to-urban migration, escalating urban slums, crimes and poverty.

V. Conclusion

The study found trade liberalisation in agricultural commodities and increasing reliance on international trade for food supply encourages dumping of the excess products in developing countries at relatively cheaper prices. This harms domestic production and reduces the income of domestic farmers and other investors in the food production chain.

Trade liberalisation in agriculture meant that uncertainties related to international price movements became directly significant for Indian farmers as the government did not provide any assistance to absorb these price volatility shocks (Siddiqui, 1998). Under such circumstances, Indian farmers were pushed to compete against highly subsidised large farmers in developed countries. For instance, in cotton, such uncertainty has given misleading signals to farmers who responded by changing cropping patterns and did not expect a sudden fall in prices. It has also affected farmers producing soybeans and ground nuts due to palm oil imports.

The problem is that if agriculture policies are formulated on the principle of ’’free market’’ then it will have deep social and economic implications in the country. This is because, firstly, in industry, production is a continuous process, but agriculture output takes place not continuously and its output cannot be adjusted to demand conditions. Secondly, the agricultural scale of operations takes place on a much smaller basis e.g., in a country like India, agriculture operations are dominated by small and medium farms rather than industry. Thirdly, agriculture output fluctuates due to weather and other natural factors. Fourthly, farmers holding stocks after harvests are also very limited, meaning agriculture supply cannot be increased rapidly. Fifthly, demand for agricultural commodities tends to be price inelastic. In short, in the presence of all factors, the agriculture sector requires government intervention in the markets (Siddiqui, 1999).

Since the mid-1990s, the WTO, IMF, and World Bank promoted trade liberalisation of agricultural commodities (World Bank, 2018). The WTO imposed trade policy, which reduced livelihood opportunities, displaced ecologically sustainable agricultural practices (Siddiqui, 2021), and created food import dependency. But in contrast to free trade and neoliberalism, food sovereignty requires domestic and national control over food production and food trade rather than market forces.

The study concludes that focusing on increasing yields by using expensive imported new seeds and chemical fertilisers and machines for large farm operations is not economically viable for African countries. They need quite different solutions based on local resources and needs and an improved understanding of intercropping and crop-livestock integration. The imposition of large-scale industrialised agriculture will destroy ecology, and crop diversity and make these countries more dependent on the West (Siddiqui, 2024).

Food sovereignty requires changes to global and local agricultural policies. Government intervention is necessary but not sufficient conditions to achieve food sovereignty. Agricultural trade is dominated by agro-food big corporations whose main objective is to maximise profits and expand markets, characterised by relentless food commodification and ’’supermarketisation’’. Corporate agriculture is driven by fossil-fuel, large-scale capital-intensive industrially driven big farms. This has squeezed petty commodity producers worldwide and especially undermined food security and food sovereignty while increasing vulnerability and import food dependency on poor countries.

About the Author

Dr Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

Dr Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

References

- Akram-Lodhi, A.H. (2015). “Accelerating Towards Food Sovereignty”, Third World Quarterly, 36(3): 563-583.

- Kohli, A. (2004). State-directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Koning, N. (2017). Food Security, Agricultural Policies and Economic Growth Long-term Dynamics in the Past, Present and Future. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315753928

- Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton University Press.

- Murphy, S. and Hansen-Kuhn, K. (2017). “Counting the Costs of Agricultural Dumping”, Institute of Agriculture and Trade Policy, June. https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/2017-06/2017_06_26_DumpingPaper.pdf

- Siddiqui, K. (1991). “India’s Green Revolution and Rural Poor”, Bergens Tidende, (in Norwegian) June 11, Bergen, Norway.

- Siddiqui, K. (1997). “Credit and Marketing of Sugarcane: A Field Study of Two Villages in Western Utter Pradesh”, Social Scientist, 25(1-2): 62 – 93.

- Siddiqui, K. (1998). “The Export of Agricultural Commodities, Poverty and Ecological Crisis: A Case Study of Central American Countries”, Economic and Political Weekly, 33(39): A128-A137, September 26.

- Siddiqui, K. (1999). “New Technology and Process of Differentiation: Two Sugarcane Cultivating Villages in UP, India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 34(52): A39-A53, December 25.

- Siddiqui, K. (2014). “Contradictions in Development: Growth and Crisis in Indian Economy”, Economic and Regional Studies, 7(3): 82-98.

- Siddiqui, K. (2015). “Agrarian Crisis and Transformation in India”, Journal of Economics and Political Economy, 2 (1): 3-22.

- Siddiqui, K. (2018a). “The Political Economy of India’s Economic Changes since the Last Century” Argumenta Oeconomica Cracoviensia, 19: 103-132.

- Siddiqui, K. (2018b). “Development Induced Displacement: A Critical Analysis” Turkish Economic Review, 5(2): 226-239.

- Siddiqui, K. (2021). “Agriculture, Sustainable Development, and the Government Policy in the Developing Countries”, The World Financial Review, January-February, 44-59.

- Siddiqui, K. (2024). “Indian Agriculture, Role in the Economy and Economic Liberalisation: Revisited”, Forthcoming.

- World Bank. (2018). World Development Indicators. Washington DC: World Bank.