By Peter Hopkinson and William S. Harvey

The growth of interest in the circular economy has been meteoric with new initiatives emerging weekly. A key figure in this movement has been Dame Ellen MacArthur, a renowned and iconic round the world yachtswoman. In this article, the authors explore how MacArthur and her foundation have created a framework for a new economy, leading to a major movement concerning global resource challenges and how the economy operates, and what business leaders can learn from her successes in building and sustaining transformation within the circular economy.

In 2012 a report was launched at the World Economic Forum (WEF) demonstrating the economic and business case for a circular economy. Five years later, a report focussing on the application of the circular economy to address a New Plastics Economy was the highest downloaded report in the history of the WEF. In October of this year over 2,000 delegates gathered in Yokohama for the second World Circular Economy Forum. The European Union second circular economy package, impacting on industrial supply chains within and beyond the region is under consideration. (see Atasu et al., 2018 in HBR).1 Over 100 universities worldwide now feature the circular economy in one or more programmes and 17 academic journals have recently issued themed calls on the circular economy.

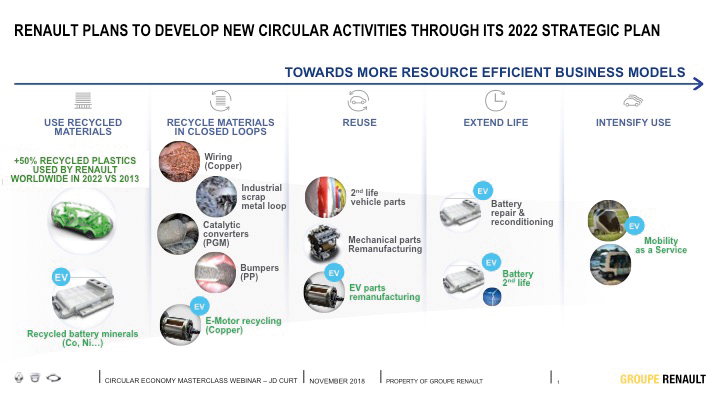

By any measure, the growth of interest in the circular economy has been meteoric with new initiatives emerging weekly. Business leaders are starting to embrace the term and are moving beyond symbolic support statements to exploring how to implement the circular economy, as examples from Danone, Philips, Renault (See exhibit on next page) and Ricoh testify. This presents significant short-term challenges but also long-term opportunities and rewards. (see Tse et al. 20162 and Esposito et al., 20183 in HBR).

A key figure in this movement has been Dame Ellen MacArthur, a renowned and iconic round the world yachtswoman, who at the age of 24 completed the Vendee Globe, the world’s toughest race. As the fastest person to circumnavigate the globe single-handedly, breaking the record in 2005 (age 28) her elite sporting status was assured. However, soon afterwards and finding herself in the Antarctic on a sabbatical after one especially gruelling race, she reflected on the abandoned industrial remnants of the whale oil industry.

“There were ships filling the harbours, some of which still line the shores today, and spare propellers and patterns for producing engine parts (…) This was a massive industry with thousands of tons of steelworks employing thousands of people and now it’s a dead, empty space.” This eventually led to her setting up the Ellen MacArthur Foundation with a mission to accelerate a transition to a circular economy.

Why is this different from many other charismatic and high achieving leaders who have established charities, foundations and done good deeds as part of an epiphany or career change? What can business leaders learn from the successes of building and sustaining transformation within the circular economy? MacArthur and her foundation have transcended a single issue focus and created a framework for a new economy, leading to a major movement concerning global resource challenges and how the economy operates.

It is one thing to identify what needs to transform, but another thing to overcome resistance to inertia. In order to fulfil its potential, both purposeful and inspirational leadership is required across every facet of business and society to persuade everyone on this planet that everything that we extract, produce and consume cannot be disposed of over time (linear economy), but must reintegrate back into our system (circular economy). How can this seismic shift in thinking and behaviour be achieved? To answer this question, we need to look at what has been achieved and how, and whether the transition can indeed be accelerated and sustained.

2008-2011. Origins

Following her Antarctica experience, MacArthur began to move away from competitive ocean racing, and spent three years travelling the world for a different purpose: to find out more about how economies work and whether it might be possible for an economy to operate in a fundamentally different way. This meant re-thinking an economic model that extracts resources, converts them into products and services which are then consumed and either disposed or replaced with new products and services. MacArthur termed this the ‘linear economy’, a throughput model that relied on relatively cheap accessible resources and fossil fuel energy, mass production and consumption and little regard for the accumulation and consequences of external costs. Some of the clues were already visible in previous iterations of ‘new economic thinking’ such as natural capitalism and performance economy, which had attracted their own followings, but failed to gain traction with business or policy makers or scale. More significantly, MacArthur noted the rise of the 4th industrial revolution and the need to harness scientific and technology revolutions in innovations and deep insights from complexity science created new opportunities to apply systems thinking to the challenge of resource depletion and natural capital degradation.

At the outset MacArthur’s message was simple – the linear economy is failing and we need a new economic model. This was not about saving the planet or an environmental agenda, but targeting a generation to think differently about the future and providing a positive alternative to a take-make-dispose model.

The core definition of a ‘circular’ economy was formulated during this time – an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design, a phrase that has stuck and been endlessly repeated to highlight the shift from a degenerative and depletive model to one that radically shifts the way we think about resources, energy and materials in the economy. MacArthur launched her foundation in 2010 supported by British telecom/Cisco National Grid, Kingfisher and Renault, which built on her prior reputation, referred to in the academic literature as reputation endowment.4 MacArthur’s sailing background created a compelling narrative around finite resources and framed as re-thinking the future economy. This was a statement of intent that this was no green or eco initiative but aiming to be on the front pages of mainstream and business global newspapers such as the New York Times5 and the Financial Times.6

2011-2014. The butterfly effect

The circular economy burst into life in 2011 when the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) presented its vision to an initially sceptical McKinsey resource efficiency team. Three months later McKinsey came back and concluded that they had ‘run the numbers’ and could demonstrate a compelling case for an economic and business opportunity at scale. Over the next 12 months more analysis and evidence was collated and the famous butterfly diagram7 was created to translate the circular economy into a simple, coherent graphic to explain the sources of value creation from multiple reverse loops. The diagram formed a centre piece of a 2012 report,8 which was launched at the WEF with a headline figure of $630 billion net material saving within the European economy from shifting from a linear to a circular economy across a number of materially intensive industrial sectors. This represented 47.8% of the EU’S GDP. On the back of this event, the EMF formed their CE100 a membership group of progressive global corporates, innovation and start-ups keen to learn more and how CE worked in practice.

2014-Today. Systemic innovation and widening engagement

Two further reports (2014, 2015) featuring analytics by McKinsey provided additional evidence in support of the business case for the circular economy. This led to spectacular growth in interest with new initiatives, networks and programmes. As a small organisation, the Foundation had a philosophy of using their limited resource to create initiatives with the potential for exponential scaling. They termed this systemic innovation – applying their core principles and building blocks of a circular economy to areas of the economy with the greatest potential for impact. One of the earliest programmes from 2015 was to address the leakage of plastics from the world economy. The New Plastics Economy programme convened many of the world’s largest brands and key players in the global plastics value to collaborate on the challenge and lead the redesign of the existing linear system to a new type of circular plastics system. An ambitious agenda, the EMF found that the partners wanted to find solutions but had been tackling these alone and lacked a systems perspective, that was crucial to aligning incentives and actions towards a common goal. The New Plastics Economy report9 launched at Davos in 2016 ramped up interest in the circular economy, coinciding with the surge of national media10 attention on the scale of the leakage of plastics into the world’s oceans.

By 2017, the circular economy had become a well-established term in Europe with the Foundation’s work playing an instrumental role in the emergence of the initial 2016 European Union circular economy package and subsequent iterations. Academic research is now firmly established after a slow start, with over 100 Universities and other prominent businesses partnering with the EMF.11 The circular economy is increasingly recognised as a key business opportunity addressing systemic challenges facing many companies and value chains. Leading companies such as Philips have set themselves targets of 15% sales from CE by 2020 and an impressive 100% by 2025.

Google Data Centre Server Operations – Circular Economy

Google Data Centre Server Operations – Circular Economy

Lessons learned and where next?

The circular economy movement has achieved major accomplishments in the last decade, which has been an outcome of four factors. First, a compelling vision of a better future, namely a transition from a linear to a circular economy that creates social and financial incentives for organisations.

Second, a prominent leader who has already achieved respect and legitimacy in another field and used this to build attention around the movement. Ellen MacArthur’s success as a world-record-breaking around-the-world sailor has helped her to capture the attention of others around the circular economy.

Third, partnering with key organisations to build awareness and acceptance. Ellen MacArthur’s work with McKinsey and the World Economic Forum, among others, for instance such as global partners and university networks, has been important in gaining the necessary examples and evidence to give others the confidence to participate in the movement.

Fourth, providing visualisation. The EMF Butterfly diagram has provided companies such as Google, a framework for starting to think about the multiple reverse value creation loops at a practical level (See diagram on the left page). The framing and adaption of this initial diagram have been instrumental in helping wider audiences to understand and visualise what the circular economy is and why it is important. This plays a similar role to a company’s brand, namely something that is recognisable and understood to hold and generate significant value.

Finally, notwithstanding the successes of the past, the next stage of any movement requires two further steps. First, it needs to be salient to a wider group of stakeholders. Thus far, the circular economy movement has been successful at engaging certain businesses, universities, and policymakers. Its success moving forward will require engagement with a much wider group of stakeholders given the systemic nature of the movement. Second and related, in order for existing groups to support and new groups to fully participate, a movement needs to provide a vision for the economic and social value of individual participation and the costs of non-participation. The media strapline in 2016 of ‘more plastic than fish in the sea by 2050’ is the kind of shock headline that captures public attention. However, sustaining a movement requires ongoing recognition from a wider group of actors that re-designing the economic system will provide greater value for them over time compared to the status quo. A 2018 exhibition Harvest,12 by British artist Mella Shaw at the Saatchi Gallery, features hundreds of detailed clay ‘plastic’ bottles and containers and leaping fish to highlight the appalling toll discarded plastics are taking on our marine-life, perhaps signals the next wave of the movement’s wider audience engagement.

This is not a doom and gloom movement. Leaders thinking about the future of their businesses in the age of VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity) are increasingly turning to circular economy as an alluringly feasible, attractive and attainable strategy compared to the linear model. There remain considerable challenges and obstacles to scaling initiatives and overcoming linear lock-in, but increasingly many business leaders view this transition as inevitable rather than impossible.

About the Authors

Peter Hopkinson is Director of the University Exeter Centre for Circular Economy that brings together academic researchers, business, policy makers and civic society to support the transition to a circular economy. He set up and ran the world’s first MBA in circular economy and a global on-line executive education programme for leading global businesses, innovation companies and educators. He is most concerned with developing the scientific evidence base for circular economy theory and practice at varying scales and within different industrial contexts.

Peter Hopkinson is Director of the University Exeter Centre for Circular Economy that brings together academic researchers, business, policy makers and civic society to support the transition to a circular economy. He set up and ran the world’s first MBA in circular economy and a global on-line executive education programme for leading global businesses, innovation companies and educators. He is most concerned with developing the scientific evidence base for circular economy theory and practice at varying scales and within different industrial contexts.

William S. Harvey is Professor of Management and Associate Dean of Research at the University of Exeter Business School. Will researches on reputation and leadership within organisations. His work has appeared in world leading journals such as Harvard Business Review, Journal of Management Studies and Human Relations.

William S. Harvey is Professor of Management and Associate Dean of Research at the University of Exeter Business School. Will researches on reputation and leadership within organisations. His work has appeared in world leading journals such as Harvard Business Review, Journal of Management Studies and Human Relations.

References

1. https://hbr.org/2018/07/rethinking – sustainability – in – light – of – the – eus – new – circular – economy – policy

2. https://hbr.org/2016/02/how-businesses-can-support-a-circular-economy

3. https://hbr.org/product/introducing – a – circular – economy – new – thinking – with – new – managerial – and – policy – implications/CMR677 – PDF – ENG

4. http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb / 9780199596706 . 001 .0001 / oxfordhb-9780199596706-e-19

5. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/06/business/burberry-burning-unsold-stock.html

6. https://www.ft.com/content/360e2524-d71a-11e8-a854-33d6f82e62f8

7. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/infographic

8. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications/towards-the-circular-economy – vol – 1 – an – economic-and-business-rationale-for-an-accelerated-transition

9. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_New_Plastics_Economy.pdf

10. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jan/19/more – plastic – than – fish – in – the – sea – by – 2050 – warns – ellen – macarthur

11. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org / our – work / activities / universities /network – universities

12. https://www.recirclerecycling.com/mellashaw/