Over the centuries, the study of economics has produced a profusion of trade theories, each aspiring to model the real-world dynamics of international trade. Here, Kalim Siddiqui discusses the varying degrees of success with which different trade theories have viewed trade in the context of developing countries.

Introduction

Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) emphasises that nations should, instead of pursuing the accumulation of trade surpluses and gold, engage in free trade. Through the division of labour, countries could specialise and focus on producing the goods in which they have absolute cost advantages and import the goods that would have been more expensive to produce domestically. Removing trade barriers would allow for expanding the size of the market, which was previously confined to national borders, and the exchange of commodities would leave all nations involved better off.

Later David Ricardo (1917) introduced comparative advantage theory. Ricardo showed that countries could still benefit from trade, even in the absence of absolute advantages. Like Smith’s argument of the “invisible hand”, however, Ricardo strictly assumed that capital would not move across borders. This article contributes by re-examining the role of trade theories in developing countries and critically examines these theories and assumptions.

The comparative advantage model emphasises the idea that labour costs must be kept low in labour-surplus economies to take advantage of free trade. The neoclassical model assumes the existing distribution of returns as natural market outcomes, meaning that there is no need for workers to struggle for higher wages. The neoclassical model does not consider how pre-existing social differentiation shapes market outcomes and thus cannot account for inequalities within the labour market. The neoclassical theory also ignores the accumulation of capital and how historically resources were transferred from colonies to Europe, and this has played a vital role in modernisation and economic development in Europe (Siddiqui, 2020a; 2020b).

According to the international institutions, Ricardo’s comparative advantage theory provided the economic rationale for developing countries to liberalise their trade. It is assumed that full capacity utilisation will lead to efficiency gains and specialisation of the production of goods and services in which the country has its comparative advantage. A country could increase aggregate output by adopting trade liberalisation, which could lead to welfare enhancement for all participating partners. The founders of “free trade”, namely Adam Smith and David Ricardo, were very clear about the immobility of capital in their model and regarded the exchange of capital- or labour-intensive commodities as a perfect substitute for factor mobility (Siddiqui, 2018a, 2018b).

The rationale of larger market and efficiency-seeking corporations is to enhance their position in domestic and global markets to secure monopolistic rents so that patterns of production and trade can be altered to their benefit. The mainstream economists do not question how these countries became rich and powerful and how colonies were forced to adopt an “open trade” policy in the 19th century.

It seems that economic and trade relations are important and contribute to economic changes in a country. In an idealistic situation in the capitalist economic system, international trade and production are supposed to be undertaken by small private businesses that would not have the power to influence and set prices. It is hoped that trade among countries is made to benefit all partners. However, in the real world, this may not be true, and unequal relations including neocolonialist practices are pursued by economically, technologically, and militarily powerful countries. Unequal trade perpetuates inequality between nations and makes the capitalist system vulnerable and unsustainable over the long term (Bieler and Morton, 2014).

International Trade Theories

Adam Smith advocated a greater division of labour and specialisation and he expected this would increase productivity. Smith defended “free trade” and, in the last quarter of the 18th century, the nascent capitalist class opposed excessive interference in the state, though he argued for public provision of education for all. He ignored the violence of primitive accumulation and the necessity of centralised state intervention to create markets (Siddiqui, 2020c).

David Ricardo’s model and mainstream trade theory (also known as neoclassical trade theories) incorrectly proclaim the universal benefits of trade. They ignore the historical facts that, in the 18th and 19th centuries, a great deal of trade had been coercive and brute force was used to implement so-called “free trade” by the colonising powers. It was argued that there were mutual benefits arising from specialisation and exchange based on the assumption that all countries can produce all goods, which is not true and, due to climate barriers, European countries cannot produce goods of the tropical climate.

The Swedish economists Heckscher and Ohlin’s(H-O) model argues that a country’s exports depend on its resource endowment, whether it is labour-abundant or capital-abundant. If a country is capital-abundant, then it will produce and export capital-intensive goods, which will be cheaper. Likewise, a labour-abundant country will produce and export labour-intensive goods. The H-O model has the following assumptions, such as zero transport costs, perfect competition in commodity and factor markets, production functions are homogeneous, and consumers’ tastes are the same in both trading countries. Some contradictions seem to be that there is a lack of initiative from the government to explore other production possibilities and make changes and no scope for diversification. The H-O model ignores institution rigidities like poor financial markets, labour policies, and domestic inflation.

David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage continues to have an important impact on trade policy. In addition to this, the H-O model stresses that if the country can produce a commodity at lower costs than another country as propagated by comparative advantages, then it leads to gains from trade. However, the theory ignores how former colonial countries’ economies are closely linked and dependent on advanced capitalist countries through trade, investment, and political and cultural relationships. His model does not consider how today’s industrialised countries at the beginning of their industrialisation phase benefited from active state intervention. In the late industrialisation countries like Germany, Japan, and the US, state intervention was crucial in the early stages of their industrialisation and clearly these countries defied “comparative advantage” and market signals.

Stolper and Samuelson’s (1941) model expanded on the Heckscher-Ohlin model by adding how changes in prices affect the return to each factor employed in production, whilst maintaining essentially the same assumptions. They found that an increase in the price of a good magnifies the rewards of the factor intensively used in its production, and the returns to the other factor decline. Such changes in factor prices, in turn, lead to adjustments of input factors. Factor substitution and changes in relative factor endowments lie at the core of factor price equalisation (Stiglitz and Charlton, 2006).

In recent decades, the role of foreign direct investment (FDI) has been incorporated into the neoclassical trade theory, which suggests the reallocation of production into low-wage countries where the costs of production are lower. However, in the Ricardian and H-O trade model, FDI is ruled out as it assumes that capital and labour are immobile factors. Considering the role of FDI would mean accepting capital mobility, i.e., capital exports and imports. This would affect factor endowments and comparative advantage. Foreign capital seeks market and efficiency to increase profits by combining capital and new technology with cheap labour.

The greater reliance on foreign capital seems to be due to cost-minimising and / or revenue-maximising considerations. Kindleberger (1964) argues that cost-minimisation and revenue-maximising strategies require firms to set up factories in expanding new markets, since it is cheaper and more efficient to serve the local market through local production. Vernon’s product life cycle (PLC) theory is another variant of linking FDI to a basic cost-minimising consideration, as he argues that the main reason for overseas investments lies in cost-based rationality. As technology matures, competition increases, the companies react by reallocating and setting up production plants abroad to low-wage countries.

The neoclassical trade theories, also known as New Trade Theory (NTT), broadly accept the comparative advantage model that gains from international trade arise independently of comparative advantage, including globalisation, i.e., trade and capital liberalisation and the restructuring of global value chains (Selwyn, 2021).

However, the NTT proves to be more realistic by assuming, inter alia, economies of scale, differentiated products, and monopolistic competition (Krugman, 1985). NTT attempts to explain the mode of serving foreign markets through classical trade theory, rather than a critical engagement with comparative advantage theory, on which most of today’s development and trade policy relies. The NTT seeks to explain larger macro-economic outcomes, including trade patterns, so that differences in labour productivity or factor endowments remain the focal point of economic analysis. The assumption of factor immobility is equally widespread in NTT, even in models that incorporate transnational firms. Monopolistic rents in this literature usually stem from monopolistic market structures as such, which are assumed to be given. Hence, it is possible to reconcile the operations of monopolistic firms with a neoclassical framework and standard trade theory assumptions, but it remains unquestioned as to how this market structure emerged in the first place, where FDI may have been a contributing factor.

Vernon’s (1970) trade theory took into account the role of foreign capital and technology and drew attention towards the “product-life-cycle” model. Innovation which led to the adaptation of new technology in the developed countries was considered to introduce new products that were produced and consumed and exported to the rest of the world, after which the “maturing” of the product was supposed to move away to other less developed countries. Less developed countries initially import these products from developed countries during the first two stages of production. But gradually as products are matured, the less developed countries start producing these goods, thus completing the life cycle of the product.

Vernon’s “product-life-cycle” trade model encompasses three stages of development: 1) Introduction, the invention of a new product, the inventor country produces and exports to other countries. 2) Standardisation – when other countries imitate, and the inventing countries lose the market. 3) Maturation – where the new technology / product becomes very competitive, and the inventing country becomes a net importer of the product. The key point of this model is that the diffusion of new technology takes place slowly and, in the end, all countries benefit from invention. When the new product is introduced, the inventing country has only a domestic market and this situation is typically characterised by high per-unit costs, low-price elasticity of demand, and monopoly power over the product design. It suggests the prevalence of imperfect competition. The critiques say that this life-cycle-product model is very deterministic. It fails to identify why there is imperfect knowledge in the world. This model tells us that innovations take place in some countries because of differences in the development of science and technology due to the existence of high-quality research institutions and education systems. The model ignores global power relations.

Vernon’s “product-life-cycle” trade model encompasses three stages of development: 1) Introduction, the invention of a new product, the inventor country produces and exports to other countries. 2) Standardisation – when other countries imitate, and the inventing countries lose the market. 3) Maturation – where the new technology / product becomes very competitive, and the inventing country becomes a net importer of the product. The key point of this model is that the diffusion of new technology takes place slowly and, in the end, all countries benefit from invention. When the new product is introduced, the inventing country has only a domestic market and this situation is typically characterised by high per-unit costs, low-price elasticity of demand, and monopoly power over the product design. It suggests the prevalence of imperfect competition. The critiques say that this life-cycle-product model is very deterministic. It fails to identify why there is imperfect knowledge in the world. This model tells us that innovations take place in some countries because of differences in the development of science and technology due to the existence of high-quality research institutions and education systems. The model ignores global power relations.

In contrast to supply-side explanations of the patterns of trade, an alternative model was presented in terms of “overlapping demand” by Staffan Linder (1961). A range of consumer goods are demanded by countries with similar per capita income. His intra-trade theory argues that patterns of trade are based on “product differentiation”. Soon after, attempts were made to introduce economies of scale in production and the impact of increasing returns which can mutually benefit from trade. Market structure and the size of firms were seen to be linked with economies of scale. This model accepted “imperfect competition” and monopolistic competition, where products were differentiated. This was a deviation from classical trade theory and competitive markets.

The NTT model argues that the producers could influence the market by exercising control over prices as well as market share. This could result in the development of monopolistic competition or oligopoly. Paul Krugman (1981) argues that this permits cost reduction on a global scale while moving production away from countries where costs are higher. Intra-trade in both directions is possible when markets are segmented and firms adopt price discrimination to maximise revenue by taking advantage of the different demand elasticities for the same goods in different countries. More theories were developed related to imperfect competition such as the “strategic trade” theory. Brander and Spencer (1985) presented situations when demand curves are subject to elasticities that are different in both trading countries. For example, Boeing and Airbus’s strategy was one of aggressive pre-emption by creating a market niche through subsidised exports. This model agrees to extend the protection of infant industries policy for a country in the name of building “strategic industries”.

The World Development Report (2020) stresses that comparative advantage trade theory asserts that development led by the “global value chain” (GVC) creates mutual gains for both the companies and suppliers. The report notes: “GVCs allow countries to benefit from the efficiency gained from a much finer international division of labour. GVCs exploit the fact that countries have different comparative advantages not only in different sectors but also in different stages of production within sectors.” (WDR, 2020: 69).

The comparative trade theory was propagated by David Ricardo that countries can benefit from trade even if they do not have an absolute advantage in the production of any good, but if they opt for specialisation in those goods where they have relatively higher productivity. By pursuing comparative advantage, international trade generates win-win outcomes where all trading countries can maximise their incomes and consumers are able to buy cheaper goods. Milberg and Winkler (2013) argue that the static efficiencies of comparative advantage trade theory are irrelevant in the contemporary world, where development is carried out through upgrading by leading firms to save their value capture strategies. As Milberg and Winkler note: “Firms within GVCs have determined the international division of labour … Suppliers have been forced to keep costs (especially labour costs) in check and to maintain mark-ups over costs at a bare minimum” (Milberg and Winkler, 2013: 315). This means that oligopolistic structures undermine competition and economic upgrading.

Paul Krugman further developed the “New Trade Theory” and emphasised that each country specialises in certain goods, as Japan and Germany specialise in car manufacturing. By doing this, they achieve economies of scale and create monopolistic competition, rather than only relying on comparative advantage. His model does not assume barriers to entry and all firms are exporters and produce and export highly similar goods.

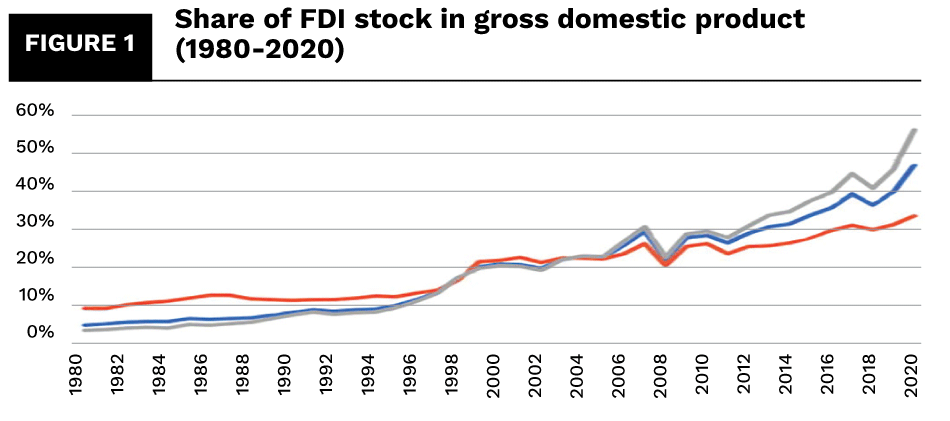

Figure 1 shows the share of the FDI stock in relation to GDP in developed and developing countries. There was a sharp rise in capital flows from the mid-1980s onwards, particularly in developed economies, The acceleration kept up the momentum approaching the 60 per cent threshold, while in developing countries, the pace slowed down after the 2008 global financial crisis. Another indicator of the role of foreign capital is the share of capital flows in relation to Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), shown in figure 2. The FDI is tied to real productive investment, which finds its way into the national economy’s GFCF. Neoclassical economists regard the development of capital stock as crucial to increasing productivity, economic growth and living conditions (UNCTAD, 2021).

Adam Smith and David Ricardo were bothered by the expectations that the idea of capitalism ended up in a “stationary state”, meaning zero growth. Karl Marx used the term “simple reproduction” to describe such a state, where there is no net addition to production capacity and the economy just reproduces itself at the same level period after period (Siddiqui, 2016).

Mainstream economists ignore the issue of relocation of capital and labour. If a country has a greater supply of capital than labour, then it is supposed to export capital-intensive products to those who are capital-scarce and import labour-intensive products in exchange. Due to climate constraints, certain commodities could grow in certain regions and this would mean that they can produce commodities which the other region badly needs (Siddiqui, 1994).

For example, Britain at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution started with the cotton textiles industry. But Britain could not grow any raw cotton, because of which the industrially pioneering country would need control over distant tropical and semi-tropical lands that could produce raw cotton and get them to supply the quantities it needs. Thus, once we move away from the fairy tale of trade occurring in accordance with “factor endowments” in a situation where the factor endowments themselves were supposedly frozen and could not migrate across country borders, then “imperialism” becomes impossible to ignore. Mainstream economists do precisely this; they ignore imperialism and explain trade as the result of capital and labour not being traded or relocated and try to explain patterns of trade due to comparative advantage.

Contemporary globalisation includes trade and capital liberalisation. The closing down of industries weakens the trades unions in the West and migrant workers, whose employment prospects depend precisely on their not being organised. At the world level, there is thus a shift in the balance of class power from the working class to the capitalists.

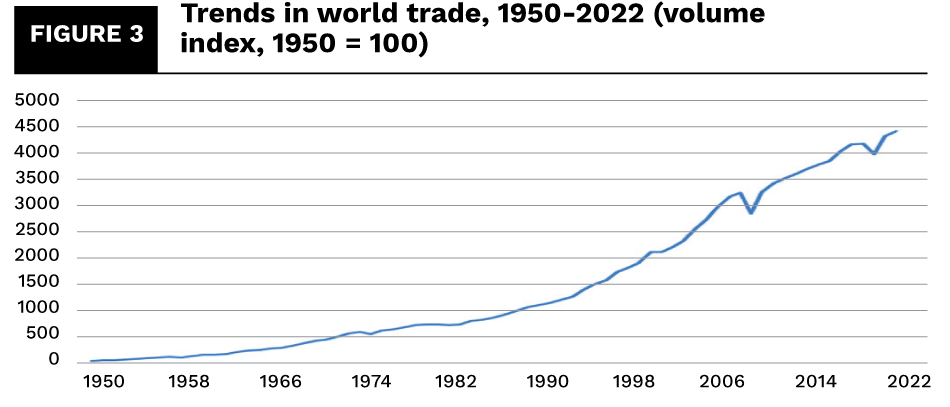

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) was formed in the early 1990s, the high point of free-market capitalism, when the answer to every problem was more markets, more private sector, and less government intervention in the market. However, since the early 1950s, the US has been trying to open markets for trade and certainly international trade in terms of volume has risen sharply, as indicated in figure 3.

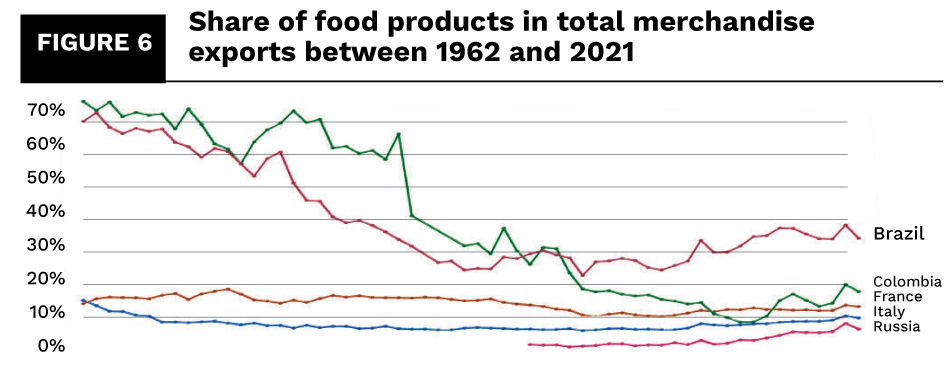

Moreover, global trade has increased in manufacturing (see figure 4) and in both goods and services (see figure 5). It was said that there was no alternative. There is no doubt that merchandise in manufacturing has risen, especially in India and Brazil. Food exports have increased, especially from countries like Brazil, Russia, France, Italy, and Columbia, as shown in figure 6. However, due to the adoption of a structural adjustment programme and trade liberalisation since the early 1990s, food imports and dependency have risen, especially in African countries, as indicated in figure 7. It is mainly because, as global trade expanded, many poor countries increasingly specialised in export crops, at the expense of food security for their populations.

This system was also based on the idea that trade was a good thing and high tariffs were usually a bad idea, but to the extent that free-trade policies didn’t achieve those goals. However, the US, the leader of advanced capitalism, had high tariffs until 1940 and only gradually removed them once its supremacy in industries and technology was achieved, and only after did the country begin extending support to free trade, as shown in figure 8.

The WTO (2013) now has the power to protect the rights of big business and big finance, undermining the ability of governments to protect their farmers and infant industries and to regulate big finance and big business. Unlike its predecessor, the WTO incorporated a dispute system with real teeth, which made the whole system enforceable.

Conclusion

Indeed, industries were more developed in Ricardo’s time in Britain compared to Smith’s time. Imports of wheat (corn) had lowered food prices and, as a result, workers’ wages were lower. Then free trade against mercantilists’ protection of domestic policies became less important. In the 1950s, the Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) model, and later Samuelson (“H-O-S” for short), played down the role of demand in the market in order to bring “resource endowments” of countries to the centre stage as the determining factor of mutually gainful trade. This means that the “free trade” model moved away from the skill- and technology-based Ricardo’s comparative advantage to an endowment-based explanation for countries, with the assumption that all countries have similar access to technology. It was also assumed that factors of production were immobile, then equalisation of commodity prices was supposed to bring about equalisation of factor prices across the trading countries.

Both Smith and Ricardo supported trade and acknowledged that international trade played an important role in economic growth by increasing market size and allowing countries to take advantage of increasing returns to scale due to the division of labour, and specialisation could encourage countries to specialise in the production of commodities in which the country has a comparative advantage (Siddiqui, 1998).

Karl Polanyi (1944), in his book The Great Transformation, warned us seven decades ago that trying to turn the whole world into a gigantic marketplace would end in the “demolition of society”. The fascism of the 1930s was the nightmare reaction that Polanyi lived through, but we see our own version of that social breakdown today and the rise of religious extremism and ethnic nationalism. If the developing countries are interested in changing unequal trade, these countries will have to work together to begin creating change on the ground and building up their own industries, supporting their small farmers, regulating, and taxing big business and big finance, and using the proceeds to build up public services, including health and education to remove people’s basic needs from the market.

Mainstream economists believe that “free trade” and openness will provide benefits to developing countries in terms of higher productivity, competition, inflows of capital, and economic growth. However, there is no empirical evidence. With trade openness, they measure the degree to which countries are open to international trade with their imports and exports. Trade openness is defined as the ratio of total trade to GDP, and represents a convenient variable routinely used for cross-country studies on a variety of issues.

The mainstream trade theories emphasise that the measure of openness is linked with higher growth, which is the trade ratio (i.e., imports plus exports divided by GDP). The problem is that it is not itself a policy variable. It is, in fact, determined by other variables in the economy, including variables like tariffs, local skills, government policy, etc. Other crucial factors could be institutions and investment climate, which could lead to both growth and more trade. The mainstream trade model implicitly accepts the status quo, which is why it is unable to deal with urgent contemporary problems such as underdevelopment, rising inequality, imperialism, racism, and environmental problems.

About the Author

Dr. Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

Dr. Kalim Siddiqui is an economist specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less-developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, UK. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and the UK.

References

- Bieler, A. and Morton, A.D. (2014). “Uneven and Combined Development and Unequal Exchange: The Second Wind of Neoliberal ‘Free Trade’?” Globalisations, 11(1): 35-45.

- Kindleberger, C.P. (1968) International Economics, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kruger, A. (1996). The Political Economy of Trade Protection, Boston: National Bureau of Economic Research. - Krugman, Paul. (1981) “Trade, accumulation and uneven development”, Journal of Development Economics, 8: 149-61.

- Milberg, W. and Winkler, B. (2013) Outsourcing Economics: Global Value Chains in Capitalist Development, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Siddiqui, K. (2020a). “Britain’s Trade with China in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century: A Review of the Opium Wars” Asian Profile 48(3): 207-21, Sept.

- Siddiqui, K. (2020b). “Prospects of a Multipolar World and the Role of Emerging Economies”, The World Financial Review, November/December, pp. 65-77.

- Siddiqui, K. (2020c). “The Study of Economic History and the Importance of Understanding the Past”, The World Financial Review, Nov/Dec, pp.46-59.

- Siddiqui, K. (2018a). “U.S. – China Trade War: The Reasons Behind and its Impact on the Global Economy”, The World Financial Review, Nov/Dec, pp.62-8.

- Siddiqui, K. (2018b). “David Ricardo’s Comparative Advantage and Developing Countries: Myth and Reality”, International Critical Thought, 8(3): 1-28, Sept. Taylor & Francis.

- Siddiqui, K. (2016). “Will the Growth of the BRICs Cause a Shift in the Global Balance of Economic Power in the 21st Century?”, International Journal of Political Economy 45(4): 315-38.

- Siddiqui, K. (2016). “International Trade, WTO and Economic Development”, World Review of Political Economy, 7(4): 424-50, winter.

- Siddiqui, K. (2015). “Trade Liberalisation and Economic Development: A Critical Review”, International Journal of Political Economy 44(3):228-47.Taylor & Francis.

- Siddiqui, K. (1998). “The Export of Agricultural Commodities, Poverty and Ecological Crisis: A Case Study of Central American Countries”, Economic and Political Weekly 33(39): A128-A137, 26 September.

- Siddiqui, K. (1994). “International Trade and Problems of Inequality in the Developing Countries”, (Eds) C. Aall and E. Solheim, Miljø Årboka (in Norwegian), pp. 20-39, Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget.

- Stiglitz, J. and Charlton, A. (2006). Fair Trade for All, Oxford: Oxford University Press. UNCTAD (2021) World Investment Report, New York: United Nations. WTO (2013). The Case for Open Trade. https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/fact3_e.htm.