Demographic shifts affect the downward decline in GDP per capita growth in G7 countries, notably Japan. Ageing is not a future problem, it is taking place now as the baby boom generation is retiring and putting pressure on the labour market and social security. Implementing the “age-free” principle, including regulatory reform, is essential in policy making.

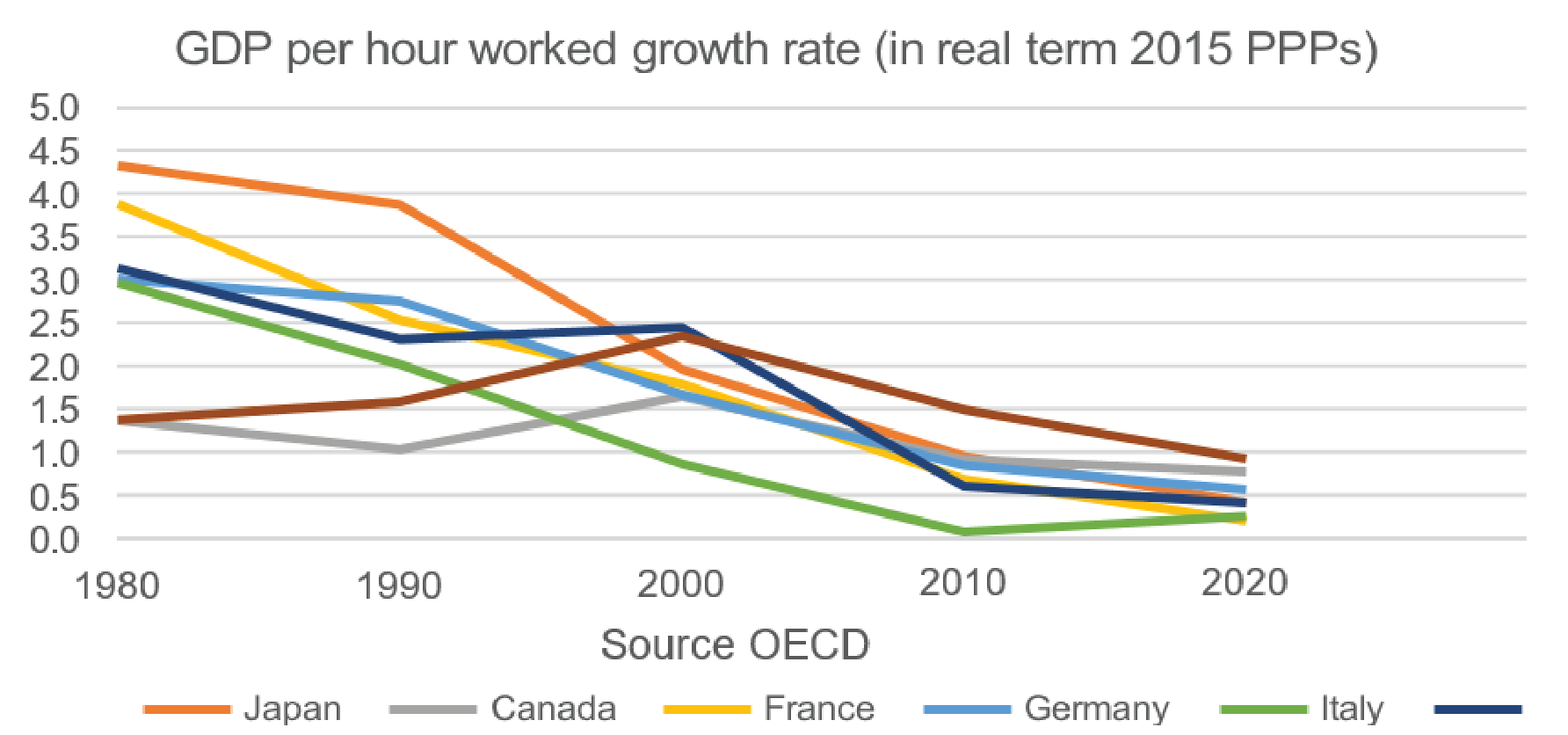

The GDP per capita growth in the Group of Seven countries has been downward since the 1990s, with Japan experiencing the most significant decline, and the United States the least (diagram 1). This trend, often referred to as “Japanification”, is usually characterised by a balance sheet recession following the bursting of an asset bubble in 1990, leading to deflation and financial stress. The inability to quickly normalise interest rates due to high debt levels associated with an increasing trend in the social security budget further indicates this trend.

While Japan has been at the forefront of this “declining productivity puzzle”, it’s important to note that the long-run demographic shift is also a critical factor in the trend. It is not exclusive to Japan, but a global phenomenon that will soon become more apparent in other G7 countries, potentially impacting their economic growth.

There is a common understanding of the negative impacts of an ageing population on economic activities. Still, one may wonder why it is happening now, or at least becoming clearer, as it has been a gradual process . An insight into the phenomenon is the ageing of the baby boomers born after the Second World War. They entered the workforce and contributed to the high economic growth post-war, but gradually got old and entered retirement age.

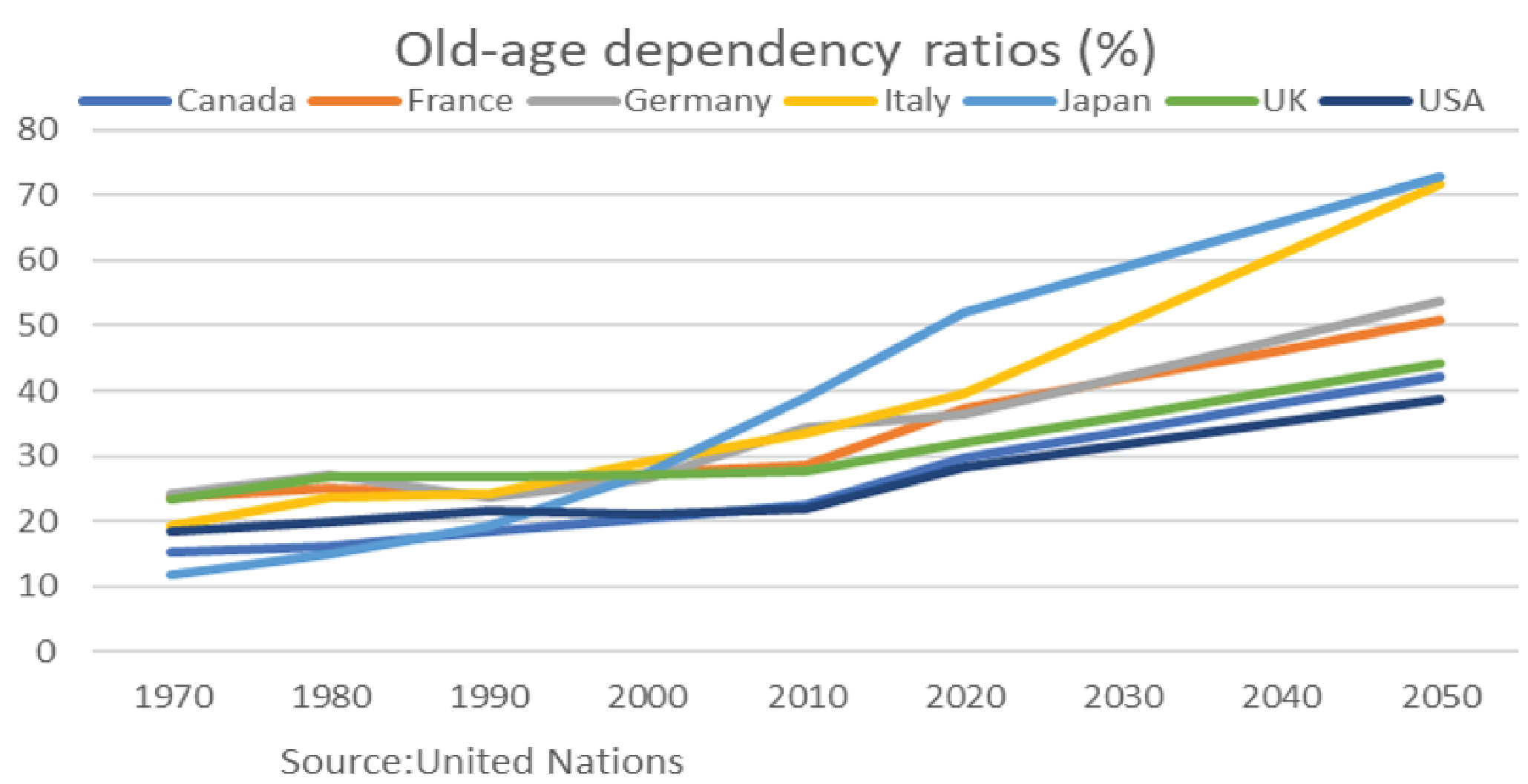

The speed at which Japan’s population is ageing is outstanding, reflecting both the high economic growth up to the 1980s and the prolonged economic stagnation. Between 2000 and 2020, the old-age dependency ratio in Japan increased from the lowest level of 27 per cent to the highest, 52 per cent, among the G7 (diagram 2).

It is crucial to learn from Japan’s experience. The current Japanese policies do not adapt quickly to modern demographics and keep economic growth low. This is mainly due to the memory of past successful economic development and efficient manufacturing industries. However, these competitive industries are migrating to other Asian countries with an abundant young labour force. The remaining agriculture and service industries, which depend on increasingly aged workers and are protected by various regulations, are not sustainable in the long run.

Given the UN demographic projection that other G7 countries will follow Japans demographic shifts in the coming decades, a key question arises: how can the UK and other G7 countries avoid the Japanification of their economies through demographic shifting?

Key Policy Issues

Diagram 1

There is a way to overcome the economic and fiscal issues arising from population ageing. An increasing old-age dependency rate results from longer life expectancy and declining fertility rates. The former arises from better social conditions, stable household incomes, sufficient healthcare services, and fewer crimes. The latter is mainly the result of households’ decisions to invest in higher education for fewer children.

Why did these people’s rational behaviours result in social problems? An increasing life expectancy implies that, on average, older adults become healthier and can work longer than before. The failure of the social system and business practices that are inconsistent with older people working longer lives should be the primary cause. The policy’s role is to encourage older people to stay in the labour market. Reskilling middle- and older-aged workers is essential in order to keep their vocational skills. Introducing the concept of “age-friendly jobs” and establishing an “age-free” society is crucial in an ageing society. This is particularly true in Japan, where age-dominant practices, such as mandatory retirement, are still prevalent.

Social security reforms to discourage earlier retirement are essential. The statutory eligibility age for a public pension should be raised to reflect an increase in life expectancy or keep the ratio of working periods in one’s lifetime constant.

Longer working lives also incentivise household savings for financing new investments. Healthcare services could keep people in good health and more employable for a longer lifespan.

Diagram 2

Labour Market Policies

The negative demographic impacts are more prominent in the labour markets. The decline and ageing of the population would constrain economic activities. Still, increasing the labour force participation of older people and women partly offsets the adverse effects of a decreasing population.

This is particularly important for an increasing number of older populations. The participation of Japanese males aged 55 to 64 in the labour force is the highest in G7 countries, but they are subject to mandatory retirement practices at age 60 to 65. The government obliges firms to re-employ their workers after mandatory retirement up to age 65, while allowing wage reductions.

This is obvious “discrimination by age” and is not allowed in many other OECD countries. However, it reflects the age-based practices of long-term employment guarantees and seniority-based wages. These practices have been established in the pyramid-like age structure of the population in the past and are no longer so rational to adopt as populations age. However, reform is politically tricky for the vested interests of old workers who suffered low wages in their younger days.

Increasing participation of females in the labour force is expected in an ageing society. Tightening labour market conditions and higher college enrolment would encourage women to enter the professional jobs formerly occupied by men. However, married women face a trade-off between pursuing professional jobs and child-raising at home. This is particularly the case in Japan and other East Asian countries suffering a rapid decline in fertility rates. This implies that the government faces a trade-off between policies encouraging more females in the labour force and increasing the number of children born.

Immigration Policy

Immigration could partly offset the declining population. However, the extent to which a country accepts immigrants varies widely. Japan was negative towards opening the door to immigrants by accepting only skilled workers, mainly white- collar college graduates. However, the definition of “skilled workers” has recently expanded to specific blue-collar jobs; for example, nurses and caregivers who care for older people, as well as construction workers. This policy change widens the range of immigrants, but the qualification of Japanese language fluency has been added for those “middle-skilled” workers. As a result, the basic policy of not accepting unskilled immigrants has been maintained.

This is because not only the quantity but the quality of the immigrants is essential. An increasing number of immigrants expands social costs, particularly their children’s school education. Although a rigid barrier for non-Japanese, language fluency is a minimum requirement for maintaining social harmonisation with immigrants.

Social Security Policies

The expansion of the public sector in the past decades has been a general phenomenon in OECD countries, which can be associated with the ageing of the population. The costs of public pensions could be controlled by keeping the proportion of retired people in the total population constant by adjusting the statutory pension eligibility age to life expectancy.

The government’s provision of healthcare services must set specific limits to prevent an explosion caused by ageing and developments in medical technology.

Increasing the efficiency of healthcare provision would be essential, as older people are heavy consumers of healthcare or nursing care services. For example, the current “fee for service” scheme in healthcare insurance in Japan is wasteful. The introduction of general physicians (as in the UK) to Japan is essential in order to reduce the healthcare costs of older patients with multiple diseases.

The ageing society is likely affected by a “silver democracy”. This is characterised by a rising number of older adults, which can exert pressure on the adequate provision of pensions, healthcare, and long-term care. This pressure would lead to increased taxes and further slow economic growth.

Moreover, older people would likely resist reforming existing schemes, often reflecting the glorious economic success of the past. This concept is prominent in Japan, with a proportionally increasing old population and the lower voting ratio of younger generations during elections. Both aggravate a vicious circle of disproportionate older people’s voices, and discourage young people’s interest in politics.

In summary, as the population ages in the G7 countries, a growing working-age population, which had been a source of economic growth, becomes an ever- increasing older population and discourages economic growth. This means that the former demographic dividend becomes a demographic drag. The negative impacts are more prominent in Japan, suffering the most significant demographic shift. However, other G7s will eventually face this risk of “Japanificiation”.

The key concept here is the “age-free” principle. This policy is essential in preventing age discrimination and encouraging older workers to stay in the labour market through government support for reskilling. An increasing working- life period with a higher life expectancy is necessary in order to finance a longer retirement through social security. Population ageing, which results from longevity, is essentially desirable for the people, and appropriate policy measures could overcome the negative impacts.

This article is the essence of the report initially prepared for the Growth Commission. https://www.growth-commission.com/research/

About the Author

Dr. Naohiro Yashiro is a professor at Showa Women’s University. Prior to joining SWU, he was president of the Japan Center for Economic Research and a member of the Council of Economic and Fiscal Policy. He is co-editor of The Economic Effects of Aging in the United States and Japan.

Dr. Naohiro Yashiro is a professor at Showa Women’s University. Prior to joining SWU, he was president of the Japan Center for Economic Research and a member of the Council of Economic and Fiscal Policy. He is co-editor of The Economic Effects of Aging in the United States and Japan.

References

- The data source is the OECD’s GDP per hour worked, accounting for an increasing number of part-time workers.

- United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision