By Terence Tse, Mark Esposito, and Olaf Groth

While Russia’s growth in the early 2000s inspired confidence in its potential as a global economic powerhouse, falling international oil prices and foreign military exploits have slowed the pace of growth and left Russia’s future uncertain. Below, the authors outline two potential scenarios and argue that only with an innovative long-term strategy focused on developing a science and technology “String of Pearls” can Russia secure its future as a global power.

By many measures, Russia exhibited stellar economic development in the first decade of this millennium. This is particularly true when you consider that Russia was still in default as a result of the financial crisis as late as 1998. By 2001, the country’s turnaround enabled Goldman Sachs to name it one of the BRIC countries, and the investment bank suggested that Russia would grow significantly in the ensuing years to become a global economic powerhouse.

In some ways, it did. The country’s GDP nearly doubled between 2000 and 2011, with an average growth rate of 4.35% per year.1 Unemployment fell from 10.5% to 6.5% in that same period.2 The proportion of people living in poverty was 33.5% in 1992, but 20 years later it was only 11.2%.3 In 2012, per capita GDP in Moscow was $44,774,4 which was more than per capita GDP in Canada and almost the same as in Switzerland. In Human Development Index (HDI) terms, Moscow was compatible to South Korea.5

All of these achievements not only painted a bright outlook for the country, but they also boosted the confidence of the nation. It is, therefore, no wonder that a Russian publication predicted in 2006 that the Russian ruble was set to become a major global reserve currency and that Moscow would soon take the stage as one of the financial capitals of the world.6 That same year, President Putin predicted that by 2009, Russia would be bigger than Britain and France in terms of GDP.7

The Devil is in The Oil

Despite this optimism, Russia has surpassed the output levels of neither Britain nor France. In 2012, it ranked eighth in terms of GDP per capita, ailing Italy but behind Brazil.8 Furthermore, Russia’s economic growth is slowing. The IMF estimates Russia’s real GDP growth in 2013 at 1.2%, which can be compared to the 4.3% seen in 2011.9

To understand the reasons for this slowdown, it is necessary to look at the main source of the country’s economic development – the price of oil. While the global economy was booming in mid-2000, the demand for energy was insatiable, which in turn pushed the oil price higher. Oil exports were not the only contributor to the economic boom; consumption rose as well. The impressive revenues from Russia’s oil sales were funneled into the rest of the economy, mostly through state-run investment projects, and through increases in wages and pensions. At the same time, most Russians had low debt and many owned their homes outright, having “inherited” them from Soviet times.10 The grand result, therefore, of rising wages was that Russian citizens had more to spend, lifting the country’s economic growth even further.

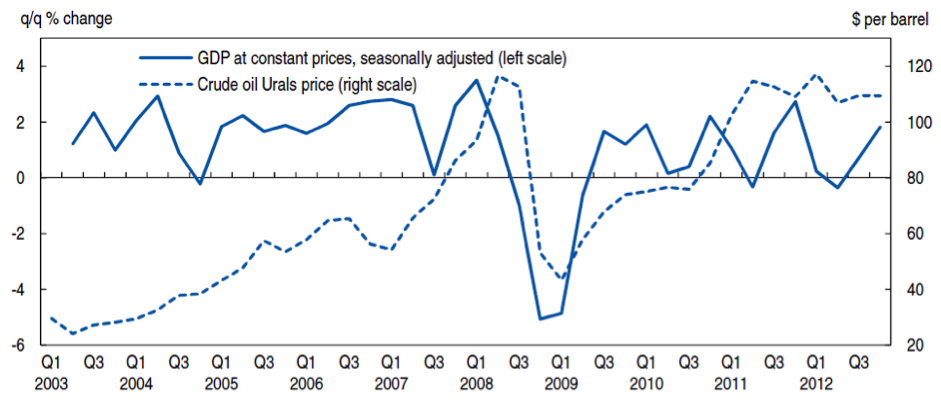

When the world economy took a dive in 2008, that demand for oil – and its price – fell significantly. The declining oil price has hit Russia particularly hard because its GDP was excessively dependent on the extraction of this natural resource (see Figure 1).11 One report suggests that a decline in the oil price of $10 per barrel would translate into a 1% loss to Russia’s GDP growth rate. If the oil price hovers at around $100 per barrel, GDP growth would be zero.12

The trouble is that demand is likely to remain low relative to the pre-2008 period, especially as Europe has made the necessary changes to lower its oil imports from Russia. Less revenue from oil and gas also means less cash for Russia’s citizens.

Furthermore, private Russian companies have made very few investments in new capacity. The excessive dependence on oil exports and the failure to improve investment habits have made it difficult for Russia to thrive in the current economic climate. Therefore, the IMF’s warning that the Russian model has probably been exhausted should not come as a complete surprise.13

Although Moscow has turned itself into a rich city, the rest of Russia has not necessarily caught up. The 2012 GDP per capita of Russia excluding Moscow put the country behind Mauritius and Panama.14 In other words, Moscow is another country, statistically speaking.15

In Need of a New Growth Model

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the Russian government may have been overconfident. It seemed to believe that the country had achieved a macroeconomic breakthrough, and that Russia would continue to grow on the back of high commodity prices and an expanding middle class.

Since the crisis, little has been done to re-invent the economic growth model to ensure sustainable prosperity. One report quoted a leading Russian thinker, who claimed that the Goldman Sachs BRIC report was “one of the worst things that ever happened to Russia.” With oil exports falling, the path to repeating past economic success has just gotten steeper and more difficult to climb.

In fact, the world is getting the impression that instead of climbing that path, Russia would rather substitute it with territorial consolidation through annexation. But what good does this annexation do? What benefit do former Soviet republics yield when most of them are in economic and political shambles with governing elites that can scarcely be called competent or stable? Can these territories yield enough gas and oil to compensate for industrial growth and diversification? Does Russia really believe that it can escape the resource curse we often call “Dutch Disease?” Can Russian resources withstand the price pressure of cheaper American and Eastern European shale gas once paired with European and Chinese nuclear, renewable, and – sadly enough – coal capacities?

There are questions over questions about the future of this BRIC-on-the-brink. It is easy to find answers that are gloomy and evoke fears of a return to the Cold War.

So then, where does Russia go from here? Maybe Winston Churchill was right once again when he proclaimed “I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.” Where does Russian national interest leave Russia by, say, 2025? We can see two contrasting scenarios:

The Saudi Arabia of Europe?

One would have Russia becoming something akin to the Saudi Arabia of Europe – a politically illiberal regime financed by oil and gas and lacking an educated and empowered public. This is not hard to imagine for two reasons: Russia’s attempts to create a “Gas-OPEC,” and the complete absence of democratic traditions in its history. Without these traditions to reference it is not likely to succeed in any attempts to turn a corner towards a web of functioning, representative and transparent market institutions that withstand populist tendencies (incidentally, a situation not unlike Germany’s Weimar Republic).

With that not happening, and absent other growth opportunities, Russia’s “GPEC” would continue to slither its gas tentacles into the near and far corners of the global economy, not just Europe. For one, Japan desperately needs gas supplies and would surely benefit from competitive bidding between the US and Russia, so as to not be beholden to a US monopoly, especially given the prospect of America’s declining hegemonic protection globally. China meanwhile is hungry for any supply of energy it can get its hands on and, as the recent supply deal between both countries proves, can use Russian resources to balance vulnerable supply lines from the Middle East through the Indian Ocean.

Speaking of the Middle East, should the region come out of its spring shuffle it will need more of its own energy supplies to grow and avoid discontent of the masses. Looking further south from there, should the Sub-Saharan African Renaissance continue to evolve, Russian supplies would surely be welcome alongside Russian infrastructure engineering and arms deliveries, if for no other reason than to create an alternative to the substantial involvement of China in Africa and an uncertain commitment from the US and Europe.

Why would the world tolerate all of this? For one, it may not have the bandwidth to take on the Russia problem since it is so busy with its own recovery in Europe and the US, and the slowdown in Asia. Additionally, Russia shares a key objective with the US and EU around the globe: keep Islamic fundamentalists at bay! Like Saudi Arabia in the Middle East, Russia views these extreme influences as a threat to its own power in former Soviet Republics. Next to Mr. Putin, there’s no room for Allah.

That is one vision of Russia in 2025. It is the one that plays on popular fears across the globe. As such, it may have become the “official future” on the “evil empire remixed.“ But helpful and constructive it is not. So why then can’t we envision a more promising path for mother Russia? Here is one to entertain:

A Global Innovation “String of Pearls?”

Imagine a world in which Russia is known for its aerospace and nautical design and systems integration, industrial scale automation, precious metal treatment, energy and mineral exploration technology, power station software, agronomy and agro-informatics for tough climates, and geo-engineering for climate change mitigation. Hard to believe? Consider Russia’s formidable science and technology legacy – arguably a thing of the past, but remnants are still present.

Russians developed the first Earth-orbiting satellite, the longest railway, the first nuclear power plant, and many other key contributions to science and technology. As a leader in these fields, they have been competing side by side with the United States. In today’s world, these are nascent techno-economic capabilities that could yield substantial geostrategic capabilities for Russia. This is especially so when considering that it has a distinct geographical advantage as well, as it sits at the base of a trade and investment triangle between Europe on one side, Asia on the other, and the Middle East with Africa at the tip. As such, Russia could become a manufacturing and assembly hub for trade in civilian goods, and, less positively, for arms and illicit substances. Latching on to the threat and the opportunity this constitutes the U.S. realised the importance of this position and has contributed $19 billion in aid to Russia (from 1992 through 2010) to facilitate the growth of democracy and retard the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.16

It is true that Russians are no longer as well educated as they used to be under the Cold War pressure and resource flow from Moscow. The country’s educational institutions have catered more to populist messaging and the vanity of its leadership than they have created true indigenous competencies.17 But there is still enough talent left, especially considering the many bright young students that have ventured out into the world absent more professionally sound opportunity at home, so as to rekindle the flame that gave the world Sputnik and many other advances previously put to dubious use.

Of course, Russia could not do this on its own. The world has advanced beyond its depository of talent. But restarting that innovation engine is no more difficult than the efforts other “BRICS,” “MINT” and “Tigers” and “Dragons” around the world have undertaken. For it to succeed, Russia needs a program that creates a science and technology (S&T) “String of Pearls,”18 to borrow a negative geopolitical term and redefine it with a positive connotation. A String of Pearls consisting of innovation clusters, “rainforests19 ” and hubs that help it build and evolve “innovation value chains” (IVCs) toward economic growth, rather than military security. These IVCs can help Russia focus its productive energies on discrete paths for the development of industrial categories, much like China has done for software, cleantech, genome processing, and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). In fact, Russia’s geography lends itself to greater efficacy in designing and harvesting the string, because it can draw on more neighbours and greater amounts of investment and trade leverage than other countries had available to them.

By way of just one example, in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, dozens of countries are in need of joint agronomic innovation projects. Africa and the Middle East are under attack from desertification and desperately need expertise in geo-engineering. And if Russia could bring itself to start and champion jointly with the US, EU, China, India, Japan and Brazil, a Global Frontier Exploration Organization for sustainable and equitable extraction of polar and space based natural resources, it would gain not just hard but soft power around the world.

This is a future worth aiming for with a new Russian national economic development strategy. It is an aspiration rather than a threatening vision for which Russian and global citizenry could be supportive. It might not get the kind of media attention that an annexation of Ukraine gets, but that is obviously a price well worth paying, we believe.

What would it take to make that happen? Russian oil and gas proceeds would need to be used now to build the String and its IVCs instead of wasting precious resources on foreign military exploits. Surely, US, EU, World Bank, IMF and IFC resources could be marshaled to support the new strategy, its S&T String and IVCs, as everyone stands to gain if Russia becomes more stable, more woven into the global economic fabric, and if they help to shape it.

In the mind of Putin, if he deems himself a good strategist, the choice should be clear: focus on moves that build competencies toward the greatest amount of options with the biggest future pay-off, not short-term attention and “eyeballs.” As with successful business strategy, successful national economic development strategy is never about a single-minded focus merely on territory and beating the competition per se, but rather on building a better model to more effectively meet the need of citizens or trading partners and lead one’s own country and others to new frontiers. Only then can the strategist hope for outsized returns and a legacy that is larger than life. To gain that stature and create that legacy, Russia needs to determine its global leadership role, invest wisely and plant its flag along new frontiers, in Donetsk and Kiev.

About the Authors

Dr. Terence Tse is Associate Professor in Finance at the London campus of ESCP Europe Business School. He is also Head of Competitive Studies at i7 Institute for Innovation and Competitiveness think-tank at ESCP Europe. He began his career in investment banking, and has worked as a consultant to a University of Cambridge-based biotech start-up and various major corporations, including Ernst & Young in London.

Dr. Mark Esposito is Associate Professor of Business & Economics at Grenoble Graduate School of Business and Instructor at the Harvard Extension School. He also serves as Senior Associate for the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership and founded the Lab-Center for Competitiveness. He has worked with governments, the UN, and NATO over the past 10 years on economic development and sustainability issues.

Dr. Olaf Groth is Global Professor of Strategy & Economics, Management & Innovation and Discipline Lead for Organization & Global Economy at HULT International Business School. He has also been a Fellow for Competitiveness at Grenoble École de Management, Senior Fellow for Innovation at the Center for Emerging Markets Enterprise at Tufts, and a judge for GE’s Ecomagination Challenge.

References

1. IMF data drawn from its website.

2. Ibid.

3. http://rbth.co.uk/news/2013/03/25/poverty_rate_in_russia_went_down_in_2012_-_russias_statistics_agency_24208.html

4. Brookings Institute, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Multimedia/Interactives/2013/tentraits/Moscow.pdf

5. Judah, B. Fragile empire: How Russia fell in and out of love with Vladimir Putin. (Cornwall: Yale University Press, 2013)

6 Judah, B. et al. ‘Dealing with the Post-BRIC Russia, European Council for Foreign Relations’. (ECFR, 2011). Available at http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/ECFR44_POST-BRIC_RUSSIA.pdf

7. Ibid. According to Judah, B. et al. (2013), the form of GDP referred to here is unclear. Nevertheless, the statement reflects the confidence of the Russian government at that time.

8. World Bank data 2013.

9. IMF (2013) World Economic Outlook: Transitions and Tensions. Available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/pdf/text.pdf.

10. Judah, B. Fragile empire: How Russia fell in and out of love with Vladimir Putin. (Cornwall: Yale University Press, 2013)

11. OECD (2013) ‘Russia – Modernising the Economy’.

12. Hedlun, S. (2013) ‘Cheaper Oil Highlights Russia’s Economic Woes’. Geopolitical Information Services report, 16 May.

13. IMF (2013) World Economic Outlook: Transitions and Tensions, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/pdf/text.pdf.

14. This is calculated based on figures providing by the Brookings Institute. Moscow’s GDP was about $520 billion, which accounts for 20.49% of the national

15. Judah, B. Fragile empire: How Russia fell in and out of love with Vladimir Putin. (Cornwall: Yale University Press, 2013)

16. Nichol, Jim. (2014) ‘Russian Political, Economic and Security Issues and U.S. Interests’. Congressional Research Service report, 31 March.

17. IBM Global Business Services. (2009) ‘Russia’s Productivity Imperative: Leveraging technology and innovation to drive growth’.

18. The term “String of Pearls” was first featured in a security context by the US Department of Defense in a report entitled “Energy Futures in Asia” and is frequently used to describe China’s efforts of securing ports and airfields around Asia to foster it’s geopolitical presence.

19. Victor Hwang. The Rainforest: The Secret to Building the Next Silicon Valley. (Regenwald, 2012)