By Michael Murphree and Dan Breznitz

In the years following the Financial Crisis, China managed to avoid recession. In this article, Michael Murphree and Dan Breznitz argue that China’s growing economic success is in great part related to its greatest innovative strengths: research and development (R&D). Whilst R&D in China, unlike in the US, tends to build on existing products, rather than developing novel technology, it is this unique approach to innovation that has allowed the country to keep up with the rest of the world. Indeed, as long as China continues to recognise this unique capability, it will not lag behind.

In the years immediately following the Financial Crisis, China was riding high. Through adroit government spending and infrastructure investment, it avoided recession. While other countries sank into economic stagnation, China continued to achieve sustained high rates of economic growth. When other governments fretted over how to revive their economies, China’s government faced the enviable position of deciding how to diversify its rich reserves of foreign exchange and where in the world its newly powerful firms should target their expansion.

In 2011, we published Run of the Red Queen, a book arguing that rather than being a developing or transitioning country, China had developed a unique and sustainable innovation and economic development system. China’s economy during the boom years of the 2000s was successful in certain sectors including electronics, IT hardware, heavy industry and infrastructure due to a combination of institutional conditions and creative, locally based, economic policy experimentation. China’s innovation system operated under institutional conditions of “structured uncertainty”. Structured uncertainty is a persistent lack of formal institutionalisation in economic governance such that the formal institutions normally mandated for mitigating uncertainty are present, but their operation and effectiveness is uncertain. Structured uncertainty incentivises specific patterns of behavior including preferences for proven business models, risk aversion and short-term profit maximisation.

Rather than being stymied by these conditions, different regions of China built on local strengths in human resources, scientific knowledge or manufacturing experience. Regions including Beijing, Shanghai and the Pearl River Delta came to specialise, respectively, in high technology startups, large-scale technology-intensive industry, and clustered light manufacturing. Each region provided both competition and support for the others in China, creating a resilient source of growth.

China’s innovation model is akin to the fast world view of the Red Queen in Lewis Carol’s Through the Looking Glass. The Queen explained to Alice that her world moved so fast that one had to run as fast as possible just to remain in the same place. In China, high technology firms innovate fast enough to keep pace with the moving global technology frontier without advancing that frontier themselves. Accordingly, Chinese firms have developed key innovation capabilities in incremental product and process innovation, sometimes also called second-generation innovation. In this model, Chinese firms build upon, adapt, reengineer and improve products and services invented in foreign countries. This is one of China’s greatest innovation-based strengths, embedded either in research and development (R&D) work for foreign brands, or in “design for production” – the ability to redesign established or foreign-invented products with the same appearance and capabilities but in a way that makes for efficient manufacturing. Indeed, it is not clear whether many of the ICT products sold worldwide could be even produced (leaving alone the question of price per unit) without the significant contribution of Chinese innovations along the production network. China did not, we argue, need to emphasise indigenous novel product innovation capabilities. Indeed, to do so would be to the detriment of Chinese capabilities, as they have developed, and would be counterproductive under global conditions of fragmented production. To sustain innovation, local governments have been highly active in shaping their local economies. Much of the innovation in China’s economy has occurred at the local level – both in private startups and foreign invested enterprises – enjoying the support and creative policies of entrepreneurial local governments. On the other hand, central government plans for promoting novel product innovation such as pushing for indigenous unique proprietary technology standards have been generally unsuccessful. Banks emphasising loans and R&D support for large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and government-affiliated industries frequently denied support to potentially innovative outsiders. This further enhanced the reliance of many firms on short-term profitability and undermined efforts at developing long-term novel product innovation capabilities. Despite these challenges, China’s innovation and economic system was sustainable and continued to yield high levels of economic growth.

The Crash

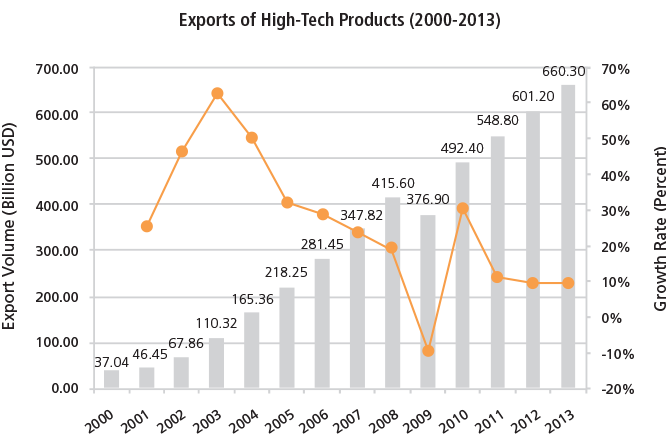

The boom years for the China’s export-led economy came to a screeching halt with the 2008 financial Crisis. Shenzhen’s economic growth rate declined by 4 points; Shanghai’s tumbled 5 percentage points, and Dongguan, a manufacturing city in Guangdong province, saw its growth rate plummet by 13 points. Such declines in growth were shocking in a China coming off a decade of growth rates well above 10 percent per year. Factory towns in Zhejiang and Guangdong provinces laid off millions of migrant workers in a matter of months. Fearing social instability as migrant workers returned unemployed to their home villages, China’s central government unveiled a $586 billion USD stimulus program in November 2008 – consisting heavily of infrastructure construction projects. Interested in sustaining their own high rates of economic growth, China’s provinces and cities also launched their own investment and infrastructure programs. Capital investment reached new heights and economic growth resumed. To encourage domestic consumption of durable and consumer goods, rural households were provided with government subsidies and other incentives to purchase refrigerators, air conditioners, televisions, mobile phones and computers. These subsidies helped stimulate short-term domestic consumption and began the process, for some firms at least, of orienting more toward the domestic market rather than exports.

However, while successful in warding off recession and controlling unemployment, China’s debt – both the official and unofficial numbers – ballooned, as did the number of non-performing loans. Furthermore, many of the construction projects such as new towns outside the major cities appeared to be ghost towns. Meanwhile, Chinese citizens with real estate and shares in booming infrastructure companies saw their wealth grow spectacularly. As a result, inequality in China has soared to among the highest levels in the world – an estimated GINI coefficient of 0.55 in 2012.

Recognising the risks inherent in growing debt and economic inequality, the Chinese government under new president Xi Jinping has begun aggressively pushing to rebase economic growth. Emphasis on innovation has reached levels even greater than those during the Hu Jintao administration. Reining in local government spending as similarly become a focus. To control public anger at the fortunes amassed by well-connected individuals, the central government has launched a massive anti-corruption campaign targeting both local and national-level officials and businessmen. These efforts have cooled China’s property market and spurred more domestic consumption, while also making government officials somewhat more timid when approving new projects and investments.

China’s Innovation Performance in the Post-Financial Crisis Era

Despite these changes, the forces we observed in the mid-2000s remain at work in China. While some firms’ strategies such as heavy reliance on exports are no longer viable, and many of the once dynamic manufacturing sectors are now struggling, China’s overall growth continues. We had predicted that China’s economic model would be sustainable for the short to medium-term. This appears to be the case as China’s continued progress follows many of the same trends we observed.

To sustain economic development, there must be continuous innovation in the introduction or improvement of services, products and processes. China has seen a steady improvement in its position as a world science and technology power. R&D spending has grown strongly year upon year – over 15% in 2013. Emphasising the centrality of market applicability and rapid utility in innovations, 76.6% of China’s R&D spending came from enterprises. In manufacturing intensive regions like Shenzhen, nearly 90% of R&D spending takes place in firms, rather than state laboratories and universities. R&D projects are thus heavily tilted toward commercial development rather than pure science (84.6% versus 4.7%). Results are intended to rapidly fuel product or process improvements that can be applied in less than two years. This builds on China’s strengths in second-generation innovation.

R&D spending collectively has now reached 2.09% of GDP, approaching the 2.74% of GDP spent on R&D in the United States. Adjusted for purchasing power parity, China is now the second largest R&D spender in the world. While researchers have noted there is significant waste in the allocation and utilisation of R&D funding, this growing pool of available resources has greatly improved China’s innovation performance. In 2014, China became the world’s top filer and recipient of invention patents. According to the World Intellectual Property Organisation, Chinese telecommunications infrastructure and mobile handset firm ZTE has been ranked first or second in global patent applications for each of the past four years. Testifying to the significance and not just size of its patent portfolio, ZTE controls 6.6% of the standards essential patents for the global 4G LTE mobile telephony standard. China’s ranking in peer-reviewed scientific journal articles has similarly climbed, again to second in the world. Government emphasis on globally recognised scientific publications has motivated academics to aggressively pursue international publication of their research. Similarly, firms are now obligated to pursue patents in order to retain their high technology enterprise status. While this has led to a well-documented increase in low quality design or marginally innovative invention patents, the growth shows a strong commitment to R&D results and performance.

The Strengths, Limitations and Future of the Chinese Economy

China remains a high-growth economy. China continues to build upon its established competitive strengths. R&D investment remains very heavily skewed towards commercial development of products and applied research rather than pure science or “core-technology” innovation. This means that although Chinese firms continue to increase their inputs into innovative activity, they are doing so based on their existing strengths in design, development and improvement, not novel-product creation. Patent statistics bear out this evidence. 69% of China’s domestic patent applications in 2013 were not invention patents. Such research activity can and does improve upon existing goods and services. It also builds capabilities or rapid adoption and scaling of new technologies from abroad. Importantly these capabilities make Chinese versions of foreign businesses such as Baidu, Tencent, and Alibaba highly targeted to the needs of the shifting Chinese market. This provides a source of sustained domestic competitive advantage but may complicate efforts to expand into foreign markets.

The central government continues to emphasise developing technology standards and indigenous innovation. Different central ministries emphasise varied approaches to technology standards development. Some ministries favour central government technology mandates backed by assurances of dedicated state procurement as an incentive for firms to develop proprietary technologies as industry defining standards. At the same time, however, Chinese firms have increased their participation in global standards efforts as well as increasing their own coalition-based standards development. Chinese high technology firms such as Huawei, ZTE and BYD are playing a growing role in global standards development efforts not only through their rapid adoption and demonstration of new technologies, but also through leadership in standards development forums. Chinese developed technology will be increasingly influential, not as an alternative to, but rather as part of global technologies. The most advanced Chinese firms will likewise expand their R&D footprint around the world. Huawei, for example, has R&D centers in seven countries (China, the United States, Russia, Sweden, India, South Africa, and Nigeria). As Chinese firms globalise, their R&D efforts will increasingly emphasise tapping specific human resource advantages – such as algorithm development in Russia or software in India.

Over the coming decade, these trends of market-relevant research, firm-led R&D efforts, and increasing global participation will continue to drive development of high technology firms in China. Firms will similarly continue to emphasise short time horizons, meaning it is unlikely that China will become the world’s leading source of novel product innovations in the short-term. Nonetheless, China will be able sustain moderate levels of economic growth, likely in the range of 5 to 7 percent per year. There will also be a continued increase in domestic consumption, as well as a growing, if gradual, awareness and market penetration of Chinese firms and brands both domestically and overseas. Chinese firms will continue to expand their global presence and importance in both markets and technology development. In many ways, the future of the Chinese economy will be one of moderating growth, in the context of deepening ties to the existing global economy – helping spur development around the world – and with increasing vested share in mutual global prosperity. Nonetheless, it will do so on a basis of its own unique institutions, not necessarily in convergence with political economic models seen in the US and elsewhere. In short, for at least the next decade the Red Queen will continue to run, and the Chinese economy and citizens will enormously benefit from it. The danger to China, we maintain, is more in forcing the Queen to stumble by the central government pushing the Chinese economy to adhere to an economic model that relies on imitating foreign innovation systems instead of China’s impressive array of unique innovational capabilities.

About the Authors

Dan Breznitz is an associate professor at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs and the College of Management, and an associate professor by courtesy at the School of Public Policy at Georgia Institute of Technology. He is author of the award-winning book Innovation and the State, published by Yale University Press, and a Sloan Foundation Industry Studies Fellow.

Michael Murphree is a project coordinator at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology.