By Ronen Palan

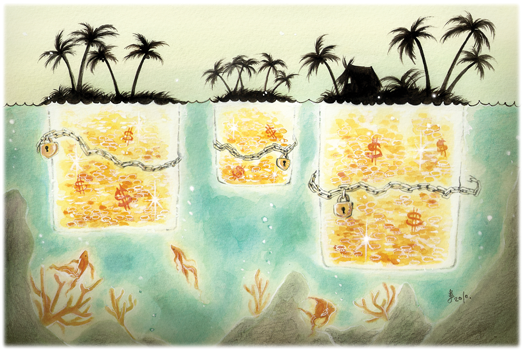

Tax havens have existed since early twentieth century, and are used primarily, but not exclusively, for tax evasion and avoidance. Tax havens are used, however, for other purposes as well. Since the early 1960s, all the premier tax havens of the world have developed financial centres known otherwise as Offshore Financial Centres (OFCs). It is estimated that about a quarter of all international lending and deposits originate in these OFCs. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) statistics of international assets and liabilities ranks the Cayman Islands as the fourth largest international financial centre in the world, while other well- known tax havens/OFCs such as Switzerland (7th), the Netherlands (8th), Ireland (9th), Singapore (10th), Luxembourg (11th), Bahamas (15th) and Jersey (19th).

In light of such staggering statistics, and the opacity that surrounds tax havens, the question that is asked perhaps not often enough concerns the link between OFCs and the financial crisis. Surprising as it may sound, to the best of my knowledge, there has never been any systematic analysis of the role played by OFCs in the crisis, certainly not by independent academics. This has resulted in some very odd schizophrenic debate. On the one hand, quasi-official research bodies claim that tax havens contributed little to the severity of the crisis. At the same time, OFCs are strongly implicated in nearly every aspect of the still unfolding financial crisis. The G-20 London communiqué of May 2009 devotes an entire section to tax havens, explicitly linking for the first time tax havens with financial instability. Not content with that, France and Germany scheduled a special meeting in June last year to coordinate their efforts in the fight against tax havens. Meanwhile, Gordon Brown sent a series of strong worded letters to British-held OFCs urging them to meet international standards on tax transparency. Why then is pressure mounting on OFCs if the same official bodies claim they have contributed little to the crisis?

A problem of Incentives

Section 1

What is then, the fundamental problem with tax havens serving as OFCs? Tax havens are specialist ‘secrecy locations’, masters of opacity. Their success hinges on a string of laws, some very familiar like bank secrecy laws, some obscure like trust laws, that ensure that the ultimate identity of asset holders may be hidden even from the tax havens‘ own governments, let alone others; that normal procedures are either very shallow or do not take place at all (In Ireland, for instance, it takes less than a day to set up a new hedge fund); that financial operators may present themselves as companies, and companies may choose to appear as financial operators, and so on. While we may have reliable data on financial flows in and out of these jurisdictions, we know precious little about what is going in them. Opacity creates a black hole in any proposed system of international regulation. This was not seen as a problem when the dominant, if mistaken view was that markets are perfectly able to self-regulate themselves, but in the post crisis situation the ability, capacity and willingness of OFCs to participate in the international efforts of financial regulation must be questioned.

One often heard argument that can be dismissed from the outset is that the leading OFCs have introduced a system of financial auditing, surveying and regulation on par with the majority of OECD countries. It is true that the shrewdest tax havens such as Cayman Islands have learned that it was in their interest to appear to cooperate with every new demand for financial regulations, and have been able to extract themselves double-quick from any potential black list. But we have to question their incentives for doing so. The financial regulations that were introduced in the past decade were never proactively thought out; they are never introduced in response to home grown problems and/or in light of a domestic constituency demands, but are always aimed at placating the Financial Stability Forum (FSF) and other such organizations. Furthermore, considering the long history of denial and obfuscation in tax matters, and their proven willingness to innovate new techniques of avoidance while appearing to comply with demands, I would argue that external auditing of these jurisdictions is absolutely necessary.

Even if an OFC is genuinely interested in improving its domestic system of regulation and surveillance, there is still a yawning gap between intent and content. Tax havens are small jurisdictions, they lack the resources, especially in terms of people, to perform appropriate due diligence on what are very sophisticated financial vehicles parked in their territories. For example, the Cayman banking system holds assets of over 500 times its GDP. Jersey holds resources of over 80 times its GDP. It seems obvious to ask whether such small jurisdictions can allocate sufficient resources to monitor and regulate such colossal sums of money. A recent report by the UK’s National Audit office has clearly suggested that they do not1. This is an area that cries out for the proverbial more independent research.

Another theory suggests that the bulk of financial transactions that make up the staggering statistics are merely booked in tax havens, and hence, the argument goes, OFCs are not the problem. The Cayman Islands’ assets and liabilities are roughly one third of the UK’s financial centres. Yet while the Corporation of the City of London reports that 338,000 were working directly in its financial centre (a figure that can be somewhat misleading, as it refers to everyone, including cleaners and security guards working in the square mile), the UK’s National Audit Office reports that only 5,400 people work in Cayman OFC. The disparity between the two figures suggests that either Cayman is an exceedingly efficient centre, or as the number implies, it is still largely a booking centre with relatively little ‘real’ banking activity.

In the Island of Jersey, a 45 square mile island with a population of 87,000, approximately 12,000 people are employed in the offshore sector. The figure is equivalent more or less to the employment figures of a decent size international investment bank, which tends to have 10,000 to 15,000 employees.

The problem with this argument is that financial operators are clearly prepared to pay the extra costs of using these jurisdictions as conduits (such as legal advice, license fees and other ‘transaction costs’) for a reason: and the reasons, unfortunately, have something to do with avoidance of one thing or another, avoidance of taxation or regulation or most probably both. If OFCs can be used for ‘regulatory arbitrage’, which was clearly the case in the past, than any proposed international regulatory regime that does not include these havens is doomed to fail. At this moment in time, it is not at all clear that OFCs are part of any proposals for new international financial regulations. Worse, as I will describe below, prior to the crisis tax havens were used extensively to avoid even some of the very minimal market-led auditing mechanisms, and I have no evidence that things have changed dramatically since then.

Section 2

By common consensus the current crisis was caused by the extraordinary level of debt available in the financial system. This happened, seemingly to the surprise of many, despite the progressive development of bank capital adequacy rules under Basle I and Basle II. The Basel Accords sought to ensure that banks maintain adequate capital ratios and are not over exposed to risks. How then did banks build such extraordinary levels of debts? It became clear amidst the unfolding crisis that banks had been using innovatory credit risk transfer techniques to remove assets from their balance sheets and free up regulatory capital for further issuance. Known otherwise as the ‘shadow banking’ system, one of the chief techniques involved the use of ‘conduits’ structured investment vehicles (SIVs) or Special Purpose Entities (SPE), known otherwise as conduit entities, funded by asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) and to reduce regulatory capital charges. The term Special Purpose Entity covers a broad range of entities; but more often than not, it is “a ghost corporation with no people or furniture and no assets either until a deal is struck” 2. These financial vehicles (or entities) were supposed to transfer assets off bank balance sheets and to other investors in the economy. In reality these vehicles were often used to increase bank’s effective leverage and exposure to aggregate risk.

We know that a considerable portion of the SPEs and other forms of structured finance at the heart of this crisis were registered in tax havens/OFCs. To what extent did the use of such offshore centres exacerbate an already dangerous situation? The vast majority of mainstream economists believe that offshore locations played no significant role in exacerbating the crisis. The FSA’s Lord Turner Review which states: ‘Some SIVs were registered in offshore locations; but regulation of banks could have required these to be brought on-balance sheet and captured within the ambit of group capital adequacy requirements.’3 A recent BIS study found ‘that it was not generally the case that investors or originators use securitisation vehicles and SPEs as a means ofavoiding tax. Rather, decisions

as to where to locate an SPE—in onshore or offshore jurisdictions—appear to be based on ensuring that the SPE vehicle itself is fairly tax neutral and thus does not impose marginal increases to a firm’s tax burden’4.

The little known case of Northern Rock and its offshore subsidiary, Granite, suggest otherwise.

Northern Rock was a UK mutual building society that was converted into a public limited company in 1997. Building societies typically raised the money they lent in a rather conventional fashion, by attracting it from depositors. Banks on the other hand, have the option of accessing larger sums from the money markets somewhat easier. After demutualization Northern Rock became a bank, and in early 2007 became the fifth largest mortgage lender in the UK. It was distinct however, from conventional commercial banks in that it had a small deposit base and relied heavily on wholesale money markets to get the funds (75%). This was an aggressive technique: the audit of Northern Rock’s accounts in 2006 showed that it raised just 22% of its funds from retail depositors, and at least 46% came from bonds.

Those bonds, interestingly, were not issued by Northern Rock itself, but by what became known as its ‘shadow company’. This was Granite Master Issuer plc and its associates, which was an entity formally owned not by Northern Rock but by a charitable trust established by Northern Rock. After the failure of the company it became clear that this charitable trust had never paid anything to charity, and that the charity meant to benefit from it was not even aware of its existence. The sole purpose of Granite was, in fact, to form a part of Northern Rock’s financial engineering that guaranteed that Northern Rock was legally independent of Granite, and that the latter was, therefore, solely responsible for the debt it issued.

This was, of course, a masquerade, and one that was helped by the fact that the trustees of the Granite structure were, at least in part, based in St Helier in Jersey. When journalists tried to locate these Granite employees they found there were no such employees in Jersey, of course. In fact, an investigation of Granite’s accounts showed it had no employees at all, despite having nearly £50 billion of debt. The entire structure was acknowledged to be managed by Northern Rock, and therefore (and unusually) was treated as being ‘on balance sheet’ of Northern Rock and was therefore included in its consolidated accounts.

Granite was used, among other things, for the purpose of obtaining the necessary rating for its securitization vehicle.

The expansion of securitization markets has given the credit rating agencies unprecedented power. The reason for this is the tradability of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) fundamentally depended on the ratings they acquired. From the very beginning of the securitization boom, a central concern to ensure the marketability of securitised debt is to enable the rating agencies to analyse and grade the credit risk of the assets in isolation from the credit risk of the entity that originated the assets. The rating analyst was not evaluating the mortgages but, rather, the bonds issued by the SPE. The SPE would purchase, in turn, the mortgages. Thereafter, monthly payments from the homeowners would go to the SPE. The SPE would finance itself by selling bonds. The question for the rating agencies was whether the inflow of mortgage checks would cover the outgoing payments to bondholders. From the investment bank’s point of view, the key to the deal was obtaining a triple-A rating — without which the deal wouldn’t be profitable.

But in order to get a separate rating for the SPE, credit rating agencies required legal opinions that the securitised assets represented a so-called ‘true sale’ and are outside the estate of the originator in the event the originator went bankrupt. The primary purpose of such a transfer of ownership is to prevent the seller and its creditors (including an insolvency official of the seller) from obtaining control or asserting a claim over the assets following the seller’s insolvency. This is true in the case of an onshore SPE, where the identity of both buyers and sellers is known, but not in the case of

offshore SPE, such as Granite. There was simply no way of knowing whether Granite was part of Northern Rock or not!

Confusion persists to this day. When Northern Rock was nationalised the House of Commons saw late night debates on whether this meant that Granite was also nationalized. Yvette Cooper, chief secretary to the UK Treasury, stated in the House of Commons that ‘Granite is not owned by Northern Rock; nor will it pass into the hands of the public sector’.5 Alistair Darling reiterated this in a letter to Vince Cable, The Liberal Democrat Shadow Chancellor, on 20th of February: “Granite is an independent legal entity owned by its shareholders… Northern Rock owns no shares in Granite’.6 Yvette Cooper however confirmed in the same parliamentary debate that ‘Granite is part of the funding mechanism for Northern Rock and it is on the bank’s balance sheet’.5

Offshore and the Crisis

‘True sale’ is an important cornerstone of the self-regulating financial market. It was assumed, not unreasonably, that the original purchaser of a securitized vehicle would make sure that the transactions were sound, and that the first purchaser of such securitized assets was better placed than the regulator to assess the value of such assets. A gigantic secondary market in such securitized bundles evolved on the assumption that the original transactions were sound. But the case of Northern Rock and Granite suggest that the original and all important transaction was taken place in fact in house, and hence the pretension of true sale was only a masquerade. It is not clear whether the purchaser of Granite bonds were aware they were buying Northern Rock’s debt or whether they were aware that the rating for these bonds were based on a false assumption of ‘true sale’.

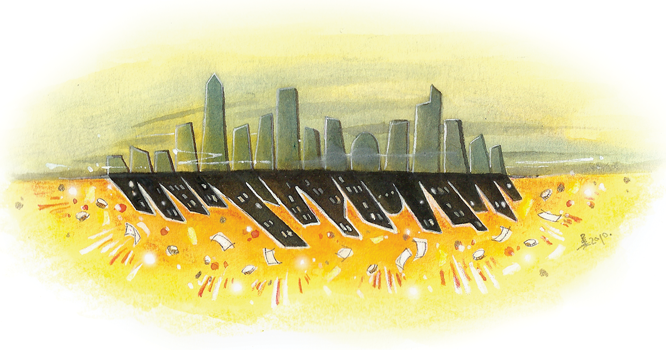

The crisis showed that the devil is in the proverbial detail. As long as the financial system appeared to perform well, few bothered to ask too many questions; but when the bubble burst, banks and financial institutions suddenly remembered that so much trading takes place either offshore or ‘over-the–counter’ (or both) and lost confidence in all published accounts, ratings, solemn declarations and the like. Financial institutions possess hundreds if not thousands of such entities, most in these secrecy offshore locations; the majority of hedge funds and other such institutions are registered in such locations. They all knew full well that just as their competitors had no way of knowing which of these entities were theirs, and whether any published account of any entity (if there were such) had anything to do with any truth, nor were they to know which of these entities belonged to which of their competitors.

In such conditions the markets simply ‘froze’: trading virtually stopped and the mountain of securitized assets whose value is the price that the next purchaser is willing to pay was heading towards ‘nil’. The financial system was effectively insolvent, and could be saved only when governments intervened and assumed wholesale responsibility for the entire debt mountain, on and off-shore.

Contrary to the mainstream view, it appears to me that the opacity produced by techniques of offshoring and ‘OTCs’ markets were at the very heart of the processes that fuelled the debt mountain, and exacerbated the crisis many time over when the bubble burst.

About the author

Ronen Palan is Professor of International Political Economy, University of Birmingham. Data and statistics for this article draws on: Ronen, Murphy, Richard and Christian Chavagneux, 2010, Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

References

1. National Audit Office (NAO), 2007, Managing Risk In The Overseas Territories, Report by The Comptroller and Auditor General, HC 4 Session 2007-2008, 16 November 2007 Foreign And Commonwealth Office. London: The Stationery Office.

2. Lowenstein, R., 2008, Triple A Failure, New York Times, 26 April 2008.

3. The Turner Review: A Regulatory Response to the Global Banking Crisis. March 2009. London: Financial Service Authority.

4. BIS, Report on Special Purpose Entities. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. September 2009. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

5. Hansard 2008, Parliamentary debates, 19 February 2008, http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk/pa/cm200708/cmhansrd/cm080219/debtext/80219-0022.htm

6. Accounting Web, 2008, Rock Bottom: How Granite Reflects on Financial Reporting, Feature. AccountingWeb, 29 February 2008. http://www.accountingweb.co.uk/cgi-bin/item.cgi?id=180124&d=1032&h=1024&f=1026