By Michele Mastroeni, Joyce Tait& Alessandro Rosiello

The encouragement of innovation has been pursued by many different governments and levels of government, as innovation is seen as a source of economic growth. While there have been some successes, many policy initiatives have been disappointing. The latest approach to innovation policy being developed in Europe is that of Smart Specialisation. This article puts forward a framework to help policymakers develop an innovation strategy that can help address some of the current limitations in the Smart Specialisation concept and which can improve the long-term efficiency and success of regional innovation policies.

Industry leaders and governments have pursued innovation as a source of economic growth for the last two decades and, while firms have been striving to harness innovation to move beyond their competitors, governments have struggled to find a way to create and maintain an environment that encourages innovation within their jurisdictional boundaries. The European Union’s efforts to encourage innovation-led economic growth predominantly focus on the regional level of governance, the most recent approach being “Smart Specialisation”.

While Smart Specialisation offers a potential solution to Europe’s challenges in pursuing its innovation agenda, we believe such an approach is limited and, based on our experience in research and policy consultation, we have proposed an alternative framework that combines the perspectives of both policymakers and innovators. This framework facilitates the development of strategy at regional and national levels and provides tools and techniques to identify and solve some of the practical challenges facing innovators and policymakers in implementation of these strategies.

The policy component of this framework should provide generalisable principles that can fit the variety of contexts and development pathways different regions will encounter. This component of our framework is a heuristic based on structural evolution, viewing economic and political activity as influenced by the actions of individual firms or organisations and also by a region’s history, resource endowment, rules, laws and practices. This component is dynamic (i.e. historically and chronologically aware of change); sensitive to its cultural and geographic context; and conscious of the fact that policy makers have different incentives from the entrepreneurs and innovators they are attempting to influence. It provides stakeholders and policymakers with the means to determine how best to nudge, push or pull different variables so that potentially innovative sectors can transition to a higher level of productivity.

We developed the second component of the framework, Analysis of Life Science Innovation Systems (ALSIS), through several life science-related research projects. However it is a technologically neutral heuristic that takes the perspective of the innovator and focuses on the development and improvement of business models, value chains, and value systems. The ALSIS heuristic can help to project emerging business models and identify possible bottlenecks and challenges that may arise in linking to international value chains.

These two components working in tandem provide a framework to design an effective regional innovation policy and also to understand and overcome the practical challenges to its implementation.

Innovation isn’t easy

A context of complexity and uncertainty

Much of the literature on innovation processes and the policy, economic and organisational settings in which innovation takes place, includes recurring themes of complexity, uncertainty and risk. Delivering an innovation to the market often requires long development timelines and the technical and scientific uncertainty surrounding many innovations means that an entrepreneurial firm can not always be sure that their entry into a market will be successful. In such cases firms are unsure about whether they can address a particular demand better than previous market entries or meet the standards of efficacy and safety needed to capture the benefits of being an innovator. This is particularly true for disruptive innovations that have the potential to transform a region’s innovative potential and competitive advantage.

Much of the empirical work informing this framework has been carried out in the area of life science based innovation – the development of new drugs, regenerative and stratified medicine, and agricultural, environmental and industrial biotechnology – areas that exemplify the roles of scientific and technical uncertainty and complexity, as well as 10-15 year timelines for development. An additional factor in these areas is the existence of sometimes uncertain, and always demanding, regulatory systems leading to even greater difficulties than in many other innovative areas in obtaining finance beyond the initial seed funding stage (the “Valley of Death”). The challenges facing the development and delivery of innovation are therefore more than just scientific or technical; they are also economic, social, and political. The question becomes more than just “will it work?” and “will they want it even if it does work?” but also “will they be able or allowed to use it even if they want it?”

Europe and Smart Specialisation

While achieving and maintaining an innovative economy is difficult for regions globally, there is a sense that Europe is facing greater challenges in some areas than its competitors (e.g. the US, China). The European Commission (EC) describes Europe’s innovation system as one made up of ‘hotspots’ of exploratory Research, Development and Innovation (RD&I), along with lagging regions; in other words it shows a centre-periphery polarisation of its innovation efforts. Thus, according to the EC, many European regions are duplicating each others’ R&D efforts, investing in developing platform technologies (e.g. biotechnology, nanotechnology, ICT) even when their European neighbours may be more advanced in the area. This leads to ‘sub-critical systems of innovation’ which are ‘unattractive’ because they do not benefit from potential economies of scale and agglomeration offered by the prospect of a common European Research Area (ERA).

In order to achieve an ERA and a strong ‘Innovation Union’, the EC has committed to the policy concept of Smart Specialisation to guide innovation strategy, where the more technologically advanced European regions would concentrate on producing cutting edge platform technologies, while entrepreneurs in other regions would develop the applications of these technologies based on their local economic needs, leading to a division of innovative labour across Europe. Ideally entrepreneurs would have EU-wide access to knowledge resources and identify how and when this knowledge can be used to create new value; and policy is directed at buoying entrepreneurs’ efforts and ensuring that they can capture sufficient value to maintain their interest in an innovation.

As currently conceived however, the SmSp approach faces several hurdles and may not be the ideal solution to enhance Europe’s growth. SmSp depends on entrepreneurs in Europe taking the lead in creating market opportunities and the EU faces problems in developing and supporting entrepreneurialism, a cornerstone of innovation. Some regions in Europe have demonstrated strong entrepreneurial capacity, e.g. Cambridge, UK; Baden Wurtemberg in Germany; Emilia Romagna in Northern Italy. However, many others lack the institutional support needed to translate entrepreneurial efforts into the critical mass that would make up a new economic sector or sub-sector that can generate economic growth or address societal concerns such as healthy ageing, food security, and sustainable energy production. Entrepreneurialism thrives best in environments where complementary institutions and organisations provide: on the supply side, education and training, finance, a labour market, and supportive rules related to firm creation; and on the demand side methods of procurement and efficient channels of distribution and uptake. Also, because many of the necessary knowledge and complementary technologies to launch a successful innovation will not be present in a single region, networks and lines of communication to facilitate national and international knowledge exchange will also be necessary. Private entrepreneurs alone will not be able to fulfil the EC’s innovation objectives; the public sector will be at least partially responsible for creating this innovation environment, and national governments, sub-national regional governments or city governments must be able to combine their efforts to ensure that the required complementary institutions are in place.

How to think about innovation policy

Technology-based innovations, in particular the more radical or newly emerging innovations, involve many untested “moving parts” (e.g. new science, new business models, new collaborations, uncertain public reactions) that make the innovation process complex and risky. Those carrying out innovative activity, or engaging in policy to support it, can be pushed, pulled and generally buffeted by a multitude of forces, often leading to unintended outcomes. Policy makers planning a regional innovation strategy should not, therefore, base their actions on a static snapshot of regional needs. By considering future scenarios such as how public preferences, institutional structures and market behaviour will change over time, policymakers can better avoid either the premature cancellation of policy or wasted investment. However, the evolution of an innovative pathway for a new niche or sector in a given region will not necessarily replicate that of other existing regional innovation systems because of the unique history and locally-specific resource endowment of a region. This means that simply taking up strategic policy models that other regions have adopted is not sufficient, and may in fact be harmful if it leads to the unsuccessful investment of resources.

The policy component of our framework, the evolutionary heuristic, helps to avoid such risks. It does so by breaking down market development and policy implementation into several discrete and consecutive events to “fill in” the space between the launch of a policy and its expected impact, and to identify points where progress can be analysed and flexibility and adjustment can be applied, depending on unforeseen circumstances or unintended consequences.

The progress of an innovation system is dependent on its ability to provide a set of key functions that facilitate the delivery of innovation from its conception to a market. Some of these key functions may be common to all innovation systems, including the provision of venture finance or the training and provision of human capital. Other functions may be specific to a particular sector or industrial activity: many of the necessary structures and functions may not occur in an economy, or will occur ‘too little and too late’ if left solely to the market. The benefit of an evolutionary heuristic applied to policy means that users will base their actions on a cycle of assessing and re-assessing their resources, their surroundings, the impact of their action and other forces, leading to more efficient policy once resources are committed.

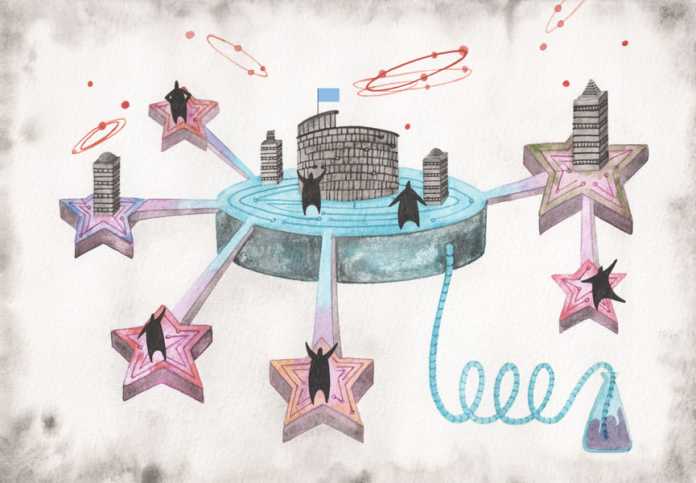

The ALSIS component of the framework, considering innovation from the perspective of the innovator, and viewing regional innovation policies as one important factor among many others that will influence the ability to deliver an innovation in a particular region, can contribute to the necessary regional innovation system building. ALSIS adopts an international perspective on innovative activity and how it interacts with the business ecosystem. It charts the sequence of actions and decisions that need to be made by a firm in developing its business model (i.e. how a firm creates, captures and delivers the value of an innovation); charts the interactions involved in the development of a value chain, considering when and how firms will need to collaborate and align their business models to deliver an innovation to a local or international market; and value system or innovation ecosystem within which a value chain is embedded (the wider economic, policy, regulatory, political and social context that can enable or constrain innovation). (Figure 1)

Most usefully in the context of regional innovation policy development, ALSIS can be used in foresighting mode to visualise how specific policies will affect the ability of a business to operate as part of a value chain within a specific region, and will determine how other components of the overall value chain can be attracted to a region in order to build a robust innovation ecosystem that is resilient in the face of future perturbations. The interactions that make up the business models and value chains can be mapped out as decision-nodes (some of which can be based on quantitative analysis and others that will require good judgement), and scenarios can be developed that foresight how different decisions and conditions can influence the effectiveness of the aggregate interactions to deliver innovation.

Considering the overall innovation ecosystem, emphasis can be given to the elements that impact on an entrepreneur’s ability to deliver innovation and as a result contribute to the effective development of a system of innovation. For example, special consideration can be given to how regulatory systems, finance or intellectual property rules will impact the decisions made at the level of the value chain or individual business model.

By applying the ALSIS heuristic to explore the innovators’ perspective and the evolutionary heuristic to explore the policy makers’ perspective, rather than the blunt instrument of a copied “best practice” applied across different regions where it may not be suitable, timely policy solutions to stubborn barriers to innovation can be developed even in an environment characterised by limited resources.

Using the Framework– how to build better policies

The ability to integrate the perspectives of policymakers and innovators addresses both the innovation challenges and the practical policy and societal issues facing Europe in its attempts to promote innovation at the regional level. The following steps are relevant (Figure 2):

1) Gather data to determine: the areas with most scientific/technological competence or industrial strength in a regional economy that could act as a focal point for SmSp activity; and also the most innovative areas, i.e. the most R&D intensive areas, the most networked areas, and areas in the economy where the most entrepreneurs are operating. These criteria may reveal overlap, or they may simply reveal individual areas of the economy from which innovations are emerging.

2) and 3) Map the region’s strengths (using the evolutionary approach) in parallel with the identification of potentially profitable value chains (ALSIS).

4) Identify the needs and bottlenecks of innovative business models and value chains in the regional value system (on a sectoral basis to capture different requirements and interactional needs in different sectors), and determine policy guidelines that can help adjust a value system’s functions so that they are adequate to meet innovator’s needs.

5) Using ALSIS scenario analysis, assess the impact of the proposed policy suite on the selected sectoral value chains, and determine where future gaps may appear in the system and what policy revisions may be needed.

6) The resulting policy suite is finalised and launched.

7) Monitor and evaluate the impact of the policy suite and make necessary modifications to adapt to changing technologies, unexpected policy opportunities/constraints, and/or unexpected stakeholder behaviours.

The strength of this joint policy/innovation framework stems from its iterative nature, assessing and re-assessing system needs from a 360˚ perspective. The attention to uncertainty and change addresses the scientific, technical, economic, social and policy complexity that faces innovators, thereby confronting the messy realities of policy making and the less-than-perfect translation of economic insights to policy actions.

The practicality of the framework is also enhanced by providing an analytical setting where the variety of stakeholder views of how the innovation system should work, or what direction a new sub-sector of the economy should take, can be incorporated. Stakeholders with a wide range of perspectives based on interests, values and ideology can, depending on the circumstances, play useful roles in decision making on innovation systems at regional and higher levels. The ideal situation is one where such consultation results in a better understanding of market opportunities or constraints so that innovation processes can be modified or re-directed in a way that reinforces social cohesion and regional prosperity.

Just as this framework benefits from a variety of insights, the entrepreneurial niches and innovative activities that are possible in an economy depend on the degree of variety within that economy. The points of convergence where different sectors interact and technologies cross over are particularly important in generating opportunities. The challenge that faces Smart Specialisation is to focus the innovative energy in an economy without limiting the variety that contributes to it, or placing specific European regions in a position where they face lock-in and lower resilience to systemic change. The Innogen Institute framework allows for an improved ability to deal with complexity and uncertainty without eliminating the creative spark that comes from an economy’s variety.

About the Authors

Michele Mastroeni is a Research Fellow at the Innogen Institute, University of Edinburgh. He has studied and advised on innovation processes and systems during the course of his research and as a former Senior Policy Advisor for the Government of Ontario. He has a PhD in Political Science from the University of Toronto.

Joyce Tait is a Professor at the University of Edinburgh and Scientific Advisor for the Innogen Institute. She has an interdisciplinary background in natural and social sciences including risk assessment and regulation, policy analysis, technology management, strategic and operational decision making in companies and public bodies. She regularly provides advice and consultation to public sector and industry stakeholders in the UK and Europe.

Alessandro Rosiellois Research Fellow at the Innogen Institute, University of Edinburgh. His current research interests include industrial organisation, industrial clusters in the domain of the life sciences and other high tech industries, entrepreneurship and small business finance, economics of innovation and regional policy.

Suggested Further Reading

• SEC(2010) 1161 Final, A Rationale For Action: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, The European and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. http://ec.europa.eu/research/innovation-union/pdf/rationale_en.pdf

• “Les Miserables”, Economist, July 28, 2012. http://www.economist.com/node/21559618

• European Commission, (2011) Cohesion Policy 2014-2020, Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation. http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/informat/2014/smart_specialisation_en.pdf

• Mastroeni, M., Mittra, J. and Tait, J. (2012), TSB REALISE Final Report: Methodology for the Analysis of Life Science Innovation Systems (ALSIS) and its Application to Three Case Studies. http://www.genomicsnetwork.ac.uk/media/REALISE%20Case%20Study%20Report%20-%20Innogen.pdf (accessed 10/04/2013)

• Mastroeni, M., Tait, J. and Rosiello, A. (2013) Regional Innovation Policies in a Globally Connected Environment. Science and Public Policy (2013) pp. 1–9

• Mittra, J. and Tait, J. (2012) Analysing Stratified Medicine Business Models and Value Systems: Innovation-Regulation Interactions. New Biotechnology, 29(6), 709-719.

• Rosiello, A., Avnimelech, G., and Teubal, M., (2011). “Towards a systemic and evolutionary framework for venture capital policy,” Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21 pg. 167-189.

• TARGET Policy Report (2011), “Targeted R&D Policy – Promoting Biotechnology: a Generalized Toolkit for Policymakers,” www.targetproject.net.