By Glyn Atwal & Soumya Jain

As the Indian luxury market enters the next phases of development, the rewards of this potentially massive market will continue to attract investment. However, India is not just another emerging market. The dynamics of the Indian luxury market challenge international luxury players to develop an Indian-driven strategy. The ability and willingness to connect with the Indian luxury consumer can make a difference between wining and losing a share of the luxury rupee. A new era beckons international luxury brands to plan strategically for the future and seize the market.

India today is a case study on how evolving consumption codes have created a consumer society founded on the bedrock of postmodernism. India’s rising economic prosperity has fuelled contemporary consumerism which is clearly exemplifying the transformation of the Indian luxury market. It is projected that the Indian luxury market will reach USD 14.72 billion in 2015¹ with unprecedented growth rates in categories from fashion to automobiles to fine dining. India has often been cited as the next China as international luxury brands enter the market to benefit from the monetary gains of a desire economy. However, the Indian luxury market is not only different compared to other emerging markets, but unique. It is a market of contrasts, contradictions and extremes. It is these opposing forces that need to be understood and integrated into business strategies if luxury players are to leverage growth opportunities and avoid the pitfalls of market failure.

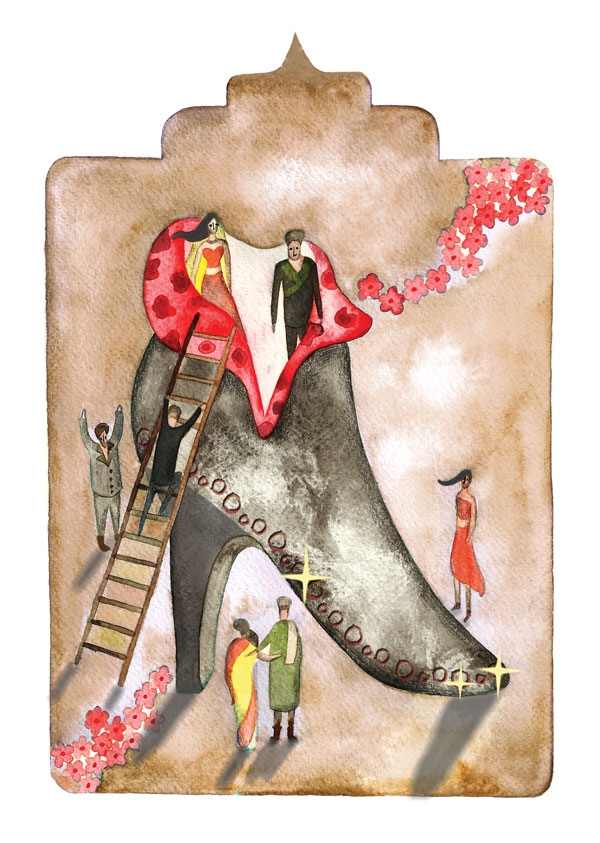

Market of Contrasts Maharajas – Masses

Luxury in India has traditionally been associated with the royal dynasty of Maharajas. Whether it was the Rajputs of Rajasthan or the Nizams of Hyderabad, luxury was in the hands of the elite. The lavish lifestyles of these aristocrats were exclusive to members of the privileged class, who had inherited not only wealth, but an inclination to acquire the finest products that were available. This was the past. The boundaries of luxury consumption have now expanded to include the masses, that is, the aspiring middle class including young professionals, entrepreneurs and well-travelled corporates. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, the Indian middle class will increase to 41 per cent of the population by 2025.² The rise of a confident consumer class, which is starting to experience premium and luxury brands, has become a symbol of an increasingly dynamic and vibrant luxury market that transcends India’s ‘old money’. The luxury market in India is a market from Maharajas to Masses.

Mega Cities – Rural India

Luxury has traditionally been bought and flaunted in the mega cities of Delhi and Mumbai. However, the luxury radar now includes pockets of consumers that go beyond the metropolitan cities. In 2008, McKinsey reported that five neighborhoods in Mumbai and Delhi and one in Punjab accounted for 65 per cent of potential luxury customers in India.³ The rich Punjabi farmers are now being joined by a growing number of small business owners, young professionals and entrepreneurs based in smaller cities such as Coimbatore and Ahmedabad. Judith Leiber receives as enthusiastic a response from Ludhiana (in Punjab) as it does from Delhi or Mumbai for its trunk shows. Giving an impetus to this trend is the growth of e-commerce within the luxury fashion domain as demand from young consumers in smaller cities and towns continue to grow and flourish. The geographical reach of luxury is no longer a big city phenomenon, but universal.

International – Indian

Aspiring luxury consumers in India desire the allure of a western logo. The badge value sends out a powerful signal that the owner has “made it” and has climbed the social ladder. It is essentially a code to depict membership to a particular social class or lifestyle. However, Indian consumers are not so simple to please. They do want to acquire the experience of owning an international, ‘logo-ed’ luxury brand, but with a local relevance. The Indian perception of luxury demands that the luxury brand celebrates the values of Indian heritage. Whether it is the sarees by Hermès or the bandhgala by Canali, Indian luxury consumers prefer a fusion of western and eastern influences. India has a unique identity of luxury.

Restraint – Conspicuousness

The philosophy of Gandhi is still deeply rooted within the Indian sentiment across all socio-economic categories. Excessive, ‘unnecessary’ spending is still frowned upon by many middle class households, which is a stark contradiction with the inner need of aspiring consumers to display conspicuousness. The fine balance between restraint and conspicuousness is a particular challenge for luxury brands in India. Montblanc came under intensive public and media pressure when it launched a Rs 1.1 million limited-edition pen containing images of Mahatma Gandhi. Critics claimed that the pen was in bad taste and was contrary to the principles of Gandhi. Luxury in India is a multi-facet concept that invokes different meanings and perceptions.

Old Luxury – New Luxury

Traditional luxury in India has been about authenticity that is precious, unique and hand-crafted. This is manifested in the strong heritage of craftsmanship that is core to traditional brands such as the Indian jewellery brand Ganjam and European luxury brands like Louis Vuitton and Cartier. Luxury in India was exclusive, reserved for the elite. Today, luxury in India is not only exclusive, but also democratic. The emergence of the ‘New Luxury’ category, defined as “products and services that possess higher levels of quality, taste, and aspiration than other goods in the category but are not so expensive as to be out of reach” 4 has created new levels of luxury. Affordable luxury brands such as Starbucks and Godiva have created an accessible level of luxury that not only focuses on giving a unique experience, but also eventually becomes a stepping stone to higher-end luxury. The scope of luxury in India ranges from the experience of drinking a latte in a coffee shop to the acquisition of diamond jewellery.

Transactional Luxury – Holistic Luxury

Luxury in India has always been about the value of the raw material. It is no coincidence that India is the world’s largest market for gold jewellery, demanding 746 tonnes of gold in 20105 Indian traditions dictate gold jewellery as a secure investment and The World Gold Council’s 2011 advertising campaign’s tagline, “This Diwali, don’t just spend. Invest.” supports the belief that the purchase of gold jewellery should be ‘worth it’. However, Indian consumers are not just demanding value for money but increasingly the exclusive experience, prestige and sophistication a luxury brand can deliver. For example, jewellery brands such as Tribhuvandas Bhimji Zaveri (TBZ), Notandas & Sons and Ganjam have developed distinctive brand identities based on design while Lodha Fiorenza is using celebrity Jade Jagger for its signature residences in Mumbai. The value proposition of luxury in India is based on rational (hard) and emotional (soft) factors.

A Luxury Dilemma

These opposing forces have created a strategic dilemma for international luxury brands in India. The catch-22 situation faced by luxury brand marketers is determining the optimal trade-off between accessibility and exclusivity. How to target the aspiring luxury consumer without alienating the mature luxury consumer? How to communicate an international brand image without losing local relevance? How to channel the attributes of “show” that are inherent to the luxury brand without consumers feeling guilty? How to deliver a value proposition that is not based solely on value for money? This raises the question how luxury brands can connect with the luxury Indian consumer that is meaningful and personally relevant. We propose the following four steps of luxury brand engagement that are key if luxury brands are to gain a sustainable competitive advantage in India.

Step 1: Generate Visibility

Generating brand visibility is essential to establish credibility and ensure social acceptance. It is, however, vital that the luxury brand is visible to the right people at the right time in the right place. Audi’s phenomenal success in India can be partly attributed to its broad aspirational appeal through its association with Bollywood. Audi is widely recognized as the preferred choice of Bollywood via its ionic association with Bollywood celebrities such as John Abraham and Ravi Shashtri. Targeted visibility is of particular relevance for high-end luxury brands to ensure that the brand is experienced in the desired environment. For example, Bvlgari and Jaeger Le-Coulture have sponsored prestigious polo tournaments while the Cartier ‘Travel with Style’ Concours d’Elegance is a heritage motoring event for those ‘in the know’. Brand visibility is not just about brand awareness, but more about communicating the story of the brand.

Step 2: Integrate Indianness

International luxury brands need to create a fine balance that integrates a brand’s global values with Indian meaning. ‘Made for India’ has already been recognized as a cornerstone of international luxury brand’s strategy. For example, when Bottega Veneta launched an India special Knot Clutch, a sterling plate was included inside it, specifying that the clutch was for India, but made in Italy. However, the notion of Indianness needs to go beyond the physical product offering. For example, The Leela Palace Udaipur offers a personal butler service to each guest, exemplifying the traditions of Indian hospitality in its service. Hidesign’s ecological commitment, on the other hand, strikes a chord with India’s desire for an image that reflects positive virtues. Lladró, in fact, launched a limited edition range of sculptures of Indian gods that resonates with India’s passion for celebration during its many religious festivals. Indianness needs to go beyond the adaptation of existing products but to be incorporated across all touch points of a luxury brand experience.

Step 3: Create Access

International luxury brands need to build strong bridges that will connect the brand with the defined target. This can be achieved by the three Ps of access: Physical, Price and Play. Physical access is derived by breaking down the physical barriers between the luxury brand and the consumer. For example, bypassing the usual hotel arcades and luxury malls, Hermès opened a stand-alone store on an Indian high street in 2011. However, access can also be restricted in order to ensure proximity for High Net Individuals (HNIs). For example, The Belvedere is a members-only club at the luxury hotel Oberoi. Price access enables consumers to access different levels of luxury that correspond to differing levels of sophistication and ultimately price points. For example, the aspiring luxury consumer is able to access an affordable Audi A6 which could serve as a bridge to more luxurious models such as the R8 in the future. The third strategy of play access gives consumers an opportunity to experiment with luxury. At the Miele Experience Center in Delhi visitors are encouraged to interact and engage with the brand that includes exclusive events, where renowned chefs create original dishes using Miele ware. International luxury brands need to seek a mix of channels of access to bring luxury closer to emerging and mature luxury consumers.

Step 4: Develop Relationships

International luxury brands need to develop meaningful interactions. The need to win the consumer’s confidence and build trust was demonstrated when Tanishq, the jewellery retail chain by Tata Group, was launched. The customer response was initially subdued. It was only after the company supplied ‘karat meters’ to its outlets that business really moved forward. This karat testing finally convinced the consumer about the authenticity, and therefore the real value of the metal, in their jewellery. However, relationships need to move beyond a transactional relationship to communicate a dream value. One example is Harley-Davidson that organizes rides and events through HOG (Harley Owner’s Group) in India. Harley enthusiasts are able to share their common passion through a shared community. Relationships are ongoing and holistic that involves and immerses the consumer at an emotional level.

Creating the Balance

Prestige needs to be created which convey a sense of distance from the masses, yet does not make a brand off-limits. Luxury brands need to appeal to the classes in order to have relevance to the masses. This distance is essential to give marketers a rich palette for creating effective luxury brand management strategies. This task of creating distance to evoke prestige needs to be consistent with all brand interactions and coherent with the sentiment of the luxury consumer. Luxury in India is and will remain a tale of paradoxes.

About the authors

Glyn Atwal is an Associate Professor of Marketing at Burgundy School of Business, an international Graduate School of the French network of Grandes Ecoles. His teaching and research expertise includes luxury marketing and emerging markets. Prior to academia, Glyn worked for Saatchi & Saatchi, Young & Rubicam, and Publicis. He is the co-editor with Soumya Jain of The Luxury Market in India: Maharajas to Masses(Palgrave Macmillan). Soumya is the Chief Editor & Chief Executive Officer of LuxuryFacts, an online luxury magazine. She is also a visiting lecturer in luxury marketing at leading business schools in India. Prior to LuxuryFacts, Soumya was a member of the editorial staff for the magazines MillionaireAsia India and Asia-Pacific Boating India.

References

1. CII and A.T. Kearney (2011) India Luxury Review 2011, http:// www.atkearney.in/images/india/pdf/India-Luxury-Review-2011- CII-AT-Kearney-Report.pdf

2. McKinsey Global Institute (2007) The ‘Bird of Gold’: The Rise of India’s Consumer’s Market, http://www.mckinsey.com/locations/ india/mckinseyonindia/pdf/India_Consumer_Market.pdf

3. McKinsey (2008) The Great Indian Bazaar, http://csi.mckinsey. com/ExtranetSearchResults.aspx?q=great%20bazaar

4. Silverstein, M. and Fiske, N. (2003), Trading Up: The New American Luxury, New York: Penguin Group

5. World Gold Council (2011) Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2010