This article offers novel insights into how executives can build social capital by affecting and, in some cases, manipulating structure, culture, strategy, inter-company networks and stakeholder orientation. The author uses Janine Nahapiet and Sumantra Ghoshal’s application of social capital theory as the basis for grounding this article and adding to the research. Practical guidelines for executives provide a more effective facilitation of social capital in companies.

Introduction

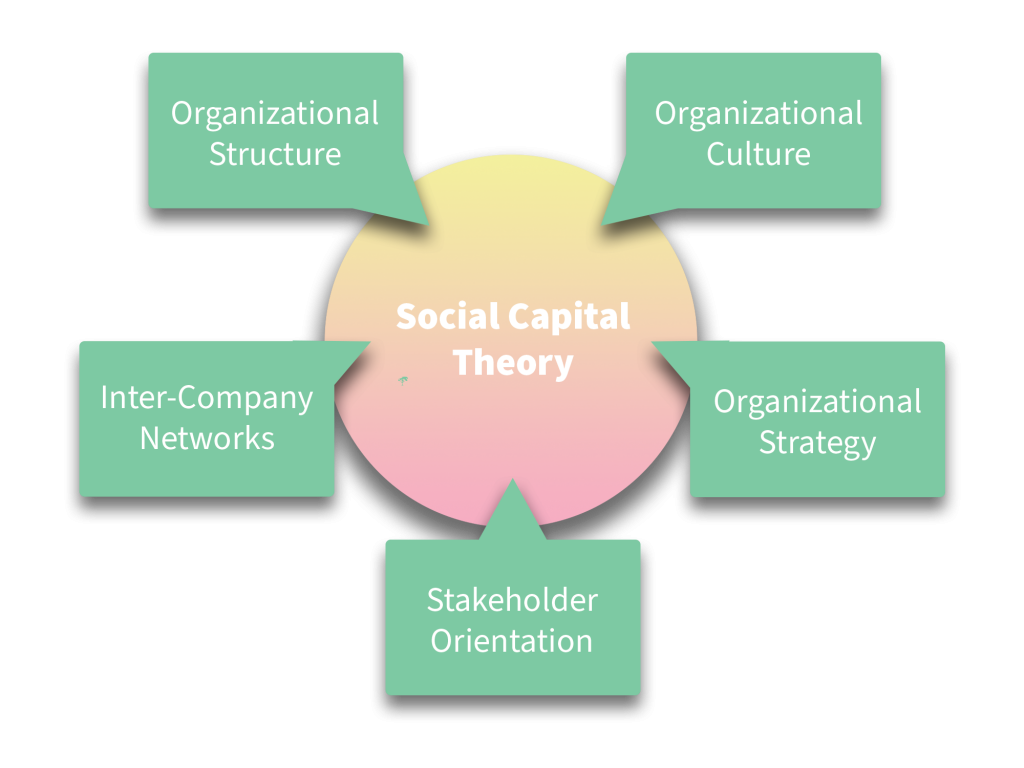

There is a gap in the management literature toward identifying the catalysts of social capital in organizations. The question arises whether the management of company characteristics can be a source for building social capital. This basic question remained unexplored since the inception of the social capital theory to date. To address this gap, this article indicates how the three important dimensions of social capital theory (structural, cognitive, and relational) are affected by various internal characteristics of companies such as the structure, the culture, the strategy, the inter-company networks, and the stakeholder orientation. The significance of my strategic tenets and networking suggestions relate to social capital theory.

The contribution to the management literature lies in presenting a theoretical framework that incorporates the organizational factors that may impact the three dimensions of social capital. The literature, to date, has failed to provide a comprehensive framework which incorporates all of the contextual factors that may simultaneously impact social capital. The absence of this systematic approach inhibits the development of social capital as a vital driver of business success. Exploring these organizational factors and how they may impact offers practical implications for executives and top managers to improve outcomes at the organizational level and meet their business objectives. This article contributes to practice by identifying the ways in which to build social capital in companies.

Building Social Capital in Companies

Janine Nahapiet and Sumantra Ghoshal determine three dimensions for social capital, and categorize them as structural, cognitive, and relational.1 The structural dimension actually portrays an “overall pattern of connections” among actors.2 This dimension could possibly be improved by having access to other actors quickly, and enhanced through highly flexible structures. Two scholars by the names of Catherine Wang and Pervaiz Ahmed indicate that highly flexible structures such as organic structures may be prone to better socialization among organizational departments and business units.3 These scholars also indicate that structural aspects of formalization and centralization may negatively relate to structural dimension of social capital theory.

The cognitive dimension is also defined as resources developing shared vision, interpretations and feelings among actors.1 Similarly, Edgar Schein, one of the prominent management scholars, defines organizational culture as “the correct way to perceive, think, and feel” in order to solve organizational problems.4 Robert Putnam, Robert Leonardi and Raffaella Nanetti found that “trust is an essential component of social capital,” and argue that trust enhances interactions among employees.5 In agreement, Ester Villalonga-Olives and Ichiro Kawachi consider trust as an important facilitator of social capital.6 The link presupposed here provides significant evidence that social capital requires cooperation, and cooperation demands collaborative behaviors. Furthermore, Salvador Avila Cobo argues that collaboration is a strong determinant of “the very existence, strength, and durability of social capital.”7 The assumption made by this literature review is that cognitive dimension seeks to achieve a shared vision. Shared vision is a mutual understanding toward determined goals, and this common perception could be reached through developing learning opportunities. These results suggest that cultural aspects of trust, collaboration, and learning may be positively associated with the cognitive dimension of social capital theory.

Another important component, the relational dimension focuses on the importance of relations, and argues that relations based on obligations, reciprocity and identification could develop organizational assets. Janine Nahapiet and Sumantra Ghoshal define obligations as “a commitment or duty to undertake some activity in the future.”1 Sort of a due diligence of each employee to put in the necessary effort to help the organization prosper. In order for a company to prosper, executives must develop a strong organizational strategy. Organizational strategy is evaluated as “a plan for interacting with competitive environments to achieve organizational goals”.8 Strategy highlights the critical role of relations with external actors, and enhances social interactions with business units and the organizational environment in order to attain goals in the future. Furthermore, organizational strategy develops a shared interpretation among organizational members and positively relates to cognitive dimension of social capital theory. Organizational strategy can be, therefore, positively connected to cognitive and relational dimensions of social capital theory.

Reciprocity, another aspect worth noting, stresses upon helping behavior and knowledge contribution between resources and recipients. Inter-company networks are a key part of this relationship, and play a critical role in enhancing knowledge transference among actors. Two scholars by the names of Elinor Ostrom and T. K. Ahn illustrate that inter-company networks are crucial condition for reciprocity, and highlight the importance of inter-company networks in creating reciprocity.9 Furthermore, one scholar that is well known in the Academy of Management, one of the largest leadership and management organizations in the world by the name of James Coleman argues that inter-company networks facilitate access to other actors and resources, and this could improve structural social capital which is highly affected by having access to other people quickly.10 Therefore, it may be established that inter-companies networks have a positive relationship with relational and structural social capital. This idea is capsulized by Robert Putnam who states that “the core idea of social capital theory is that networks have value.”11

The stakeholder orientation is about enhancing the exchange of knowledge with various stakeholders. And much of the knowledge exchanged with stakeholders is a result of social interactions between organizations and their stakeholders. The prominent scholar on social capital theory is Elisabet Garriga Cots who affirms the critical role of social capital in this relationship, and highlights a strong association between the dimensions of social capital and stakeholder orientation.12 I depict that based upon this literature review that the three dimensions of social capital emerge in social interactions with stakeholders. Accordingly, stakeholder orientation may be positively related to all the three dimensions of social capital. Therefore, factors affecting social capital theory are depicted in figure 1.

In Conclusion

This article extends the current literature and provides elaborative insights for executives and senior managers by modeling how the three dimensions of social capital theory can be affected by company characteristics such as the structure, the culture, the strategy, the inter-company networks, and most importantly, the stakeholder orientation. These three dimensions include structural, cognitive, and relational. This article can add to a relatively small body of literature and develops our understanding of the direct impact of company characteristics on social capital. In particular, I argue that executives can build social capital through manipulating organizational factors. Therefore, both in theory and in practice, executives can manifest themselves as change agents who have developed competencies to better manage organizational factors with the aim of fostering social capital within companies.

About the Author

Mostafa Sayyadi, CAHRI, AFAIM, CPMgr, works with senior business leaders to effectively develop innovation in companies, and helps companies– from start-ups to the Fortune 100 – succeed by improving the effectiveness of their leaders. He is a business book author and a long-time contributor to HR.com and Consulting Magazine and his work has been featured in these top-flight business publications.

Mostafa Sayyadi, CAHRI, AFAIM, CPMgr, works with senior business leaders to effectively develop innovation in companies, and helps companies– from start-ups to the Fortune 100 – succeed by improving the effectiveness of their leaders. He is a business book author and a long-time contributor to HR.com and Consulting Magazine and his work has been featured in these top-flight business publications.

References

1 Nahapiet, J., and Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage, The Academy of Management Review, vol. 23, no. 2

2 Choi, B. (2002) Knowledge Management Enablers, Processes, and Organizational Performance: An Integration and Empirical Examination, Thesis (PhD), Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

3 Wang, C.L. & Ahmed, P.K. (2003). Structure and structural dimensions for knowledge-based organizations, Measuring Business Excellence, vol. 7, no. 1

4 Schein, E.H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

5 Putnam, R.D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. (1993). Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

6 Villalonga-Olives, E. & Kawachi, I. (2015) The measurement of social capital, Gaceta Sanitaria, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 62-64.

7 Avila Cobo, S.H. (2005). Collaboration, innovation and the building blocks of social capital in the technology sector: A comparative analysis of knowledge-creating institutions. The role of individual attributes, policies and environments in the collaboration and productivity of scientists and technologists, Thesis (PhD), Stanford University.

8 Daft, R.L. (1995). Organization theory and design, Minneapolis/St. Paul: West Pub. Co.

9 Ostrom, E., & Ahn, T.K. (2003). Introduction. In Ostrom, E & Ahn, TK (ed.), Foundations of Social Capital, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

10 Coleman, J.S. (1988) Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital, The American Journal of Sociology, vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 95-120.

11 Putnam,R.D. (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community, New York: Simon & Schuster.

12 Cots, E.G. (2011). Stakeholder social capital: a new approach to stakeholder theory, Business Ethics: A European Review, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 328-341.