The triumph of the “no” vote in the Greek referendum was not a mandate for Grexit, but a new starting-point to talks. But is there room for a compromise any longer?

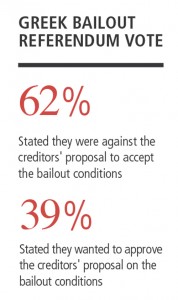

On Sunday (5 July), some 62% of Greeks voted against and only 39% for the creditors’ June 25 proposal. It was the official end to austerity policies,1 which failed the Eurozone in the early 2010s.

On Sunday (5 July), some 62% of Greeks voted against and only 39% for the creditors’ June 25 proposal. It was the official end to austerity policies,1 which failed the Eurozone in the early 2010s.

Unlike Brussels, Washington opted for very different policies – and a very different outcome.2

Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras did not resort to the referendum to end the negotiations, but to ensure a better hand. By Monday, Greek party leaders signed a joint statement, expressing common goals, including the securing of funding in exchange for reforms and seeking debt relief.

In contrast, Brussels made no secret about its support for the Greek opposition, which may have helped to unify the Greek ranks.

Right before the referendum, the Eurogroup’s uncompromising president Jeroen Dijsselboem warned that “If [the Greek] people say they don’t want [the creditors’ reform package], there is not only no basis for a new program, there is also no basis for Greece in the Eurozone.”

After the referendum, Dijsselboem reiterated that the goal was still to keep Greece in euro. However, the Netherlands’ opposition Socialist Party called for him to resign.

Parallel posturing occurred in Athens where the Eurogroup’s opposition led to the replacement of Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis with Euclid Tsakalotos, Greece’s top negotiator in aid talks with creditors.

The triumph of the “no” vote in Greece and what happens next can only be understood in its proper context.

From Misguided Bailouts to Unsustainable Debt

The Syriza-led coalition came to power in January;3 after seven years of consequent economic pain. Between 2008 and 2015, Greek per capita income, adjusted to inflation, plunged by almost a third. In 2000, it was still almost $21,000, some 17% higher than in South Korea and almost twice as high as that in Poland.

Some 15 years later, it is less than $26,000, or 40% lower than in South Korea and about the same as in Poland.

And yet, Athens did not return to markets on its own, but after two huge bailouts of €73 billion and €164 billion, respectively. By late 2014, behind-the-façade talks began over a third bailout amounting to some €30 billion.

With each bailout, Brussels vowed it would be the last one.4 But as I have argued since spring 2010, each bailout has been inadequate and none have appropriately benefited ordinary Greeks.

With each bailout, Brussels vowed it would be the last one.4 But as I have argued since spring 2010, each bailout has been inadequate and none have appropriately benefited ordinary Greeks.

At the same time, Greek public debt almost doubled in the past decade, from €183 billion in 2004 to €323 billion, or 175% of the GDP. Hence, 25% unemployment rate and youth unemployment that still exceeds 50%.

Barely 11% of the €254 billion has been spent to meet the Greek government’s current expenditure. Instead, the 2010 and 2012 agreements have been used to rescue major European private banks, particularly in Germany and France.

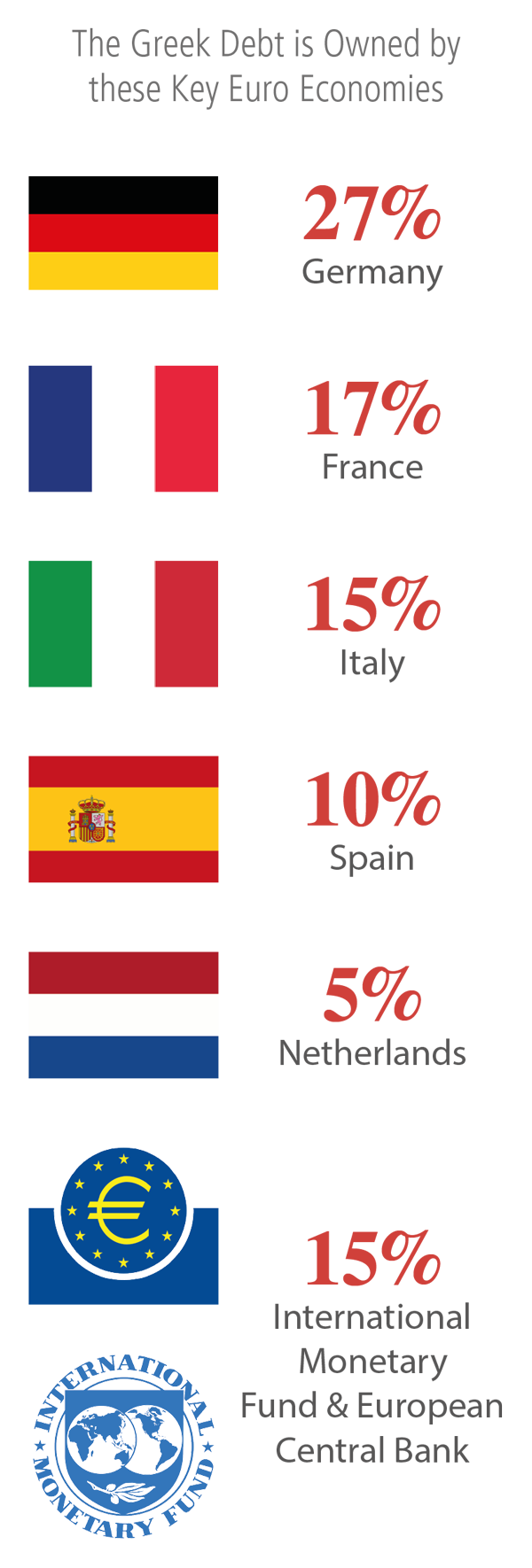

The Greek debt is owned by the key euro economies – Germany (27%), France (17%), Italy (15%), Spain (10%) and the Netherlands (5%) – as well as the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank (15%). Altogether, these countries and banks cover some 90% of the Greek debt.

The burden is particularly hard for small fiscally conservative euro economies, such as Belgium (€7.5bn), Austria (€5.9bn) and Finland (€3.7bn), which are under increasing economic pressures.

However, if you would ask the leaders of the small euro economies – not to speak of those of the big ones – would they accept more austerity after years of contractions, a collapse of living standards, doubling of sovereign debt and a huge diversion of bailout monies – the response would not be that different from the Greek referendum.

Likely Scenarios

The Greek referendum ensued after the European leaders rejected the Tsipras proposal requesting an extension of the bailout program, which expired on June 30, and the effort at a new €29.1 billion bailout package. It would have covered Greece’s debt obligations over the next two years.

That led to Greece’s de facto default on its €1.6 billion loan repayment to the IMF.

What next? There are many possible scenarios, but only a few probable ones left.

Time for final talks. In this scenario, Syriza will push its June 30 proposal, which may be modified in detail but not in substance. In turn, the creditors will argue in Brussels (and to their frustrated constituencies at home) that “a bad deal is better than no deal.” After his new political consolidation, Tsipras is well-positioned to have the new deal accepted in the Greek parliament with the support the New Democracy conservatives, Pasok social-democrats and Potami centrists. It is a compromise scenario but one that is shunned by Germany, the key pro-austerity economies and most of Eastern Europe.

Tsipras gets tough. Tsipras will use his new political muscle to argue that “Greek people demand immediate debt relief and a bailout.” But the scenario is less likely. In the referendum, Tsipras got a mandate to reject Brussels’s terms, not a carte blanche for a “Grexit.” If, however, Brussels will reject Syriza’s terms, talks would fall apart, Greece would default and face a Grexit eventually.

Creditors get tougher. The creditors will not retreat from their June 25 proposal, which the Greek referendum rejected. “We respect the Greek referendum,” they will say, “but we are accountable to all of Europe and we must honor our pledge to our own countries.” A united Greece is not likely to accept a Brussels deal that the referendum rejected. If Athens will reject a deal, Greece would default and financial stability will ensue.

In the absence of compromise, the Eurozone will move toward this scenario, which will ensure challenging tradeoffs to both Athens and its creditors.

Into Uncharted Waters

As Athens struggled to extend the closure of banks by at least a few more days, creditors began to shift toward the third scenario. French President Francois Hollande and German Chancellor Angela Merkel said that the door was open for a return to debt negotiations with Greece, but called for “serious and clear proposals” from Athens. Similarly IMF chief Christine Lagarde said IMF was ready to help Greece if asked.

At the same time, the ECB raised pressure on the fragile Greek banks and the IMF told Greece it could not provide funds to countries that had missed payments due to the international lender.

Unsurprisingly, European equity markets have been down, with the depreciation of the euro and widening spreads in the Eurozone periphery. That, in turn, has unnerved markets and economic uncertainty in the US and Asia. As a result, calls have become more vocal in Washington, Beijing and Moscow for Athens and its creditors to seek a compromise on Greece’s debt crisis that will allow Greece to remain in the Eurozone.

The time to talk is now.

The article was released on July 7th, 2015, on the EconoMonitor: www.economonitor.com

About the Author

Dr. Dan Steinbock is the research director of international business at the India, China and America Institute (USA) and a visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China). For more information, see http://www.differencegroup.net

Endnotes

1. https://euobserver.com/opinion/119392

2. https://euobserver.com/opinion/125371

3. https://euobserver.com/opinion/127653

4. https://euobserver.com/opinion/118352